|

|

With not another person for many miles, I had just finished digging my truck out of a 3-foot deep powder snow drift that I should have seen coming on a remote jeep trail in the Nevada high desert. In unusually frigid weather, I began fixing Thanksgiving dinner with my camp stove on the back door-stop of my vehicle after spending 74 consecutive nights outside when it occurred to me: perhaps people might enjoy hearing a little more about why this type of situation I have found myself in here is the norm in my life, and why, in fact, it's just the type of thing I enjoy most of all.

It was mid-September and I was leaving my base residence near Corvallis, Oregon once again for what I estimated would be 2 to 3 months of travel around the continent from north to south. Although I have inflexible obligations along the way, such as conducting photographic tours, I refuse to be held to an exact date in which I might return from such a trip.

By nature, I am bound to a perpetual state of wanderlust that has eventually shaped every part of my life. Although I have a very supportive partner of many years at home and a two-year old son I love dearly, the call of all things wild, remote, and rugged plus the desire to catch a piece of their magnificence with my camera, beckons me away as powerfully as anything. Over the years, I have been fortunate enough to both turn my love of photography and the outdoors into a full-time profession and to provide financial support for my family at home, something for which I am deeply grateful.

As a father who is away much of the year, I suppose I could have found worse professions to be involved in - such as work in the Bering Sea or Afghanistan, for example. When I am home, it is my choice to be there and every single minute I spend with my son is so precious. We have a great bond and it's only a matter of time before he's old enough to get out there more and I'll have a wide-eyed young companion with whom to share many of the wonders of the wilds in which I have found in my journeys.

For me, the ability to share something of my travels with other people has always been of nearly equal importance as the travels themselves, particularly over recent years. It was a desire to share my backpacking and mountaineering endeavors that first interested me in photography when I was around twenty. I have volunteered to lead wilderness hikes since I was about the same age while working at a local mountain shop and I have designed every one of the hundreds of trips I have ever undertaken with friends. My friends have realized things don't often go exactly as planned, but we often have all the adventure we can take! Two weeks into my recent travels, folks participating in my photo-tour at Glacier National Park would realize this as well.

I loaded up and hit the road on a sunny 80-degree day and began the 10-hour drive to northern Montana in my expedition-modified rig, a Toyota FJ. The FJ is not all that large but it's extremely capable in any driving situation, which I regularly encounter in my sixty thousand mile-per-year schedule. My list of necessary equipment for three months of travels spanning from Alaska to Arizona is considerably smaller than one might imagine, though. To picture it, realize that I can actually sleep in the back of my vehicle at night and not have to take anything else out and set on the ground. I am very much a minimalist.

I carry with me a large black 'camp-box' which contains a disorderly mess of every accessory one might generally need while camping: a hatchet, stoves, coffee, a hex-wrench set, bear-spray, knifes, rope, batteries, fine-scotch and 2 to 5 lens caps that occasionally resurface only to be lost again seconds later. I also carry a tall food-box, cooler, 1 to 3 tents, backpacking pack, day pack, camera gear, 2 sleeping bags, an assortment of reading materials and various tools such as a shovel and saw on a rack above. My bed for every single night I am traveling and not in the backcountry is located in the rear drivers-side of the vehicle in my sleeping bag atop two Thermarest mattresses. Being only 5'6" tends to help considerably with this space arrangement.

I arrived in the Blackfoot Nation lands near Glacier Park late that evening in the cold and rain. Never satisfied with campgrounds or camping-designated areas, I took off down an unmarked dirt road and then a jeep trail, bouncing through the mud, climbing in elevation, can't stop now, where is this leading, up, up, up. Wanderlust has taken hold, as usual, in the pursuit of a camping spot for the night. I came to this plateau just as the rain changed to snow and completely engulfed in fog. I notice the terrain is flat, half-open and has some really gnarly looking White Bark Pines.

"Looks like a nice spot," I think to myself. The road is probably not even on a map.

I awoke before dawn to clearing skies and striking views! There was new snow on the Glacier peaks in the distant and beautiful fall colors in the valleys below me. Within seconds of waking, I'm simultaneously brewing coffee on the back step of my rig and scouting around with camera, long lens and tripod in hand. I managed to come away with some pretty strong photos of the peaks catching the first light while sipping the brew. Naturally, instead of going back down the jeep trail the same way I came in, I decided it's best to see if I can't make a loop out of it by cutting down through the colorful Aspen on the other side of the plateau. This was the first fall color I'd seen this year, so the trip was particularly enjoyable until the trail started disintegrating when I neared what I thought would be the main road. It turned out that someone closed this entry/exit point to the plateau area many years ago by stringing a barbed-wire fence across, a mere 30 feet from the main drag. I spent the next three hours driving back over and around the way I came in and I take a few more Aspen shots and wanders on foot through the groves for my extra time.

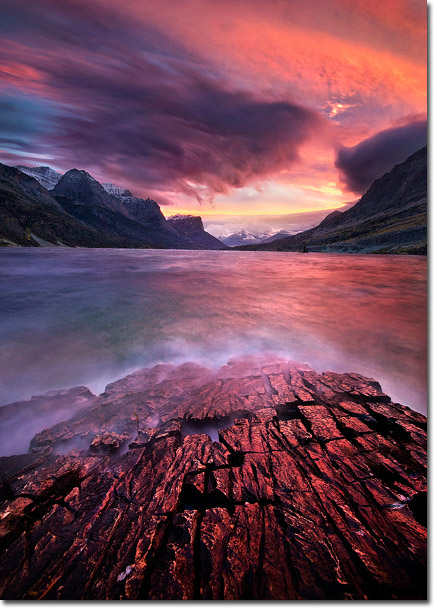

First night of the tour in Glacier National Park, Montana

I spent the next several days traveling around Glacier National Park and the surrounding areas in preparation of conducting my photo tour of the area. I use the word 'tour' and not 'workshop', because although I want my participants to ask questions and learn a great deal, I don't want to give the impression that our time will be spent in some kind of structured, sit-down, lecture-style, critique session in a classroom somewhere. I cannot bring myself to take that type of approach, even in the field. What matters most to me is the pursuit of the best photographic opportunities I can possibly show people and the means with which we go after them. When my group gathered near St. Mary Lake to begin, I promptly told everyone to throw away the itinerary I sent them. They were all camping, so lodging arrangements were a non-issue. I explained that you never know where the pursuit of nature and photography will lead. It is, above all else, a reaction to the immediate and ever-changing. If you cannot learn to keep a flexible travel schedule as a nature photographer, you will forever be at an extreme disadvantage.

I lead tours for hardy folks, such as the six I had along with me at Glacier. But I also lead other less physically demanding tours as well. In this case, I took advantage of the group's decent athletic abilities and lead them high and low throughout Glacier and the surrounding areas. Among other things, we photographed ocean-like waves pounding the lakeshore in 40 m.p.h. winds the first night, hiked 4 miles back from a valley we shot at sunset off-trail above tree line in driving rain (totally unexpected, but that's nature for you), had close encounters with bighorn sheep, mountain goats and a wolverine - all taking place within 30 minutes of each other. Later, I used my truck to ferry people up an intimidating trail to the top of a hill nearby glacier where I knew the most amazing, grizzled, wind-sculpted trees dotted the landscape and spent much of the night shooting them under the moon. For me, leading tours is much about involving oneself in the process that leads to great photographs as it is the execution of the photograph.

With my time at Glacier concluded, I was off on the road again, headed north up the Alaska Highway. A place called the Tombstone Range had beckoned me for years, located at 65.5 N Latitude, just miles short of the Arctic Circle. I had never been there, but from what I could gather, the range consisted of Patagonian-like granite peaks and spires, the likes of which could not be found anyplace else in the Arctic of North America. My plan was simple if a bit narrow in focus: to either spend big bucks on a helicopter into the range or to attempt a two-week backpacking trip into and through it, hitting the magic window of time after the first new winter snows had blanketed the peaks but while hiking could still be accomplished with relative ease with the lakes and rivers still mostly unfrozen. My ultimate objective was photography of the Aurora Borealis. I had seen a lot of Aurora photos but always believed the subject held a great deal of untapped potential.

After making the 2,500-mile drive north in a way-too-fast 3 days, I parked myself out on the Dempster Highway at the base of the range and decided upon the backpacking route into the peaks. After careful research and much experience, I had found a way to cram nearly two-weeks of food into one bear-proof canister rated for 7 days at a weight of about 20 pounds. Taking into account my equipment which consisted of a '4-season' tent (for extreme winds/snow), -40F sleeping bag (-10F and colder is not uncommon in October here), snowshoes, most of my camera gear including my most durable body, the 1Ds III, and all sorts of other heavy winter clothing, my pack, all told, weighed an unmerciful 80 pounds plus! At 150 pounds myself, I knew that was really pushing it. Only two other times had I shouldered such a load but ultimately the route didn't appear quite as difficult as expected and once I got there, I didn't have to move camp very far for a while. I planned 2 days for the hike in.

At the camp near Dawson City with my Tombstone pack

Over the course of the next two days I learned several things about both Arctic travel and photography. One of which was that bush-whacking through valleys laden with Arctic willow, particularly those covered in a foot of snow, was immensely more difficult than I thought and more a study in patience and mental fortitude than anything else. The going was painful and the 6-mile trek into Grizzly Lake took 8 exhausting hours after I lost a faint trail buried in the snow after the first mile. Upon arriving, I discovered this enormous lake at 5000-foot elevation to be 95% frozen and it was only the 6th of October! The next thing I learned is that while the peaks were indeed majestic, the lack of complimentary subject matter of the type that makes for dynamic and interesting photography is almost completely lacking in the absence of water or anything else of note standing out from the windswept and snow-covered tundra. I had planned on the lakes being more open, even at this northerly latitude or at least the rivers. The next day, I would attempt to cross the main divide of the range and find the North Klondike River valley.

It turned out to be quite a nice sunset that evening which I photographed from the only open hole in the lake before clouding up for much of the night, precluding any aurora photography. In this region, the aurora appears nearly every clear night - one just has to get a clear night in winter, not summer, as the midnight sun keeps things too bright at night the rest of the year. The forecast had been good for the first few days of my travels but I came to believe that the meteorologists in this region actually just roll dice to determine the forecasts. The weather held into the next day, however, and I reluctantly shouldered the pack again and made my way for the drifted slopes above, over the pass and slid down the backside towards Divide Lake, which, in the northern shadows of the most spectacular peaks, was 100 percent frozen. Due to the terrain again being more grueling than anticipated, I decided I'd just camp there for the night. I couldn't find the energy to move further down to the river valley below, and besides, there were some interesting fissures in the ice that might make for something of foreground interest in a landscape photograph looking up at the amazing, sheer spikes of granite towering over the opposing shore. Above all else, I really wanted to both capture the Aurora and the landscape in cohesive, dynamic fashion. That was something I had rarely seen before and was beginning to realize why.

Sunset clouds were beginning to materialize over the peaks and I was hoping it wouldn't cloud over entirely again when I went down to the ice for some photography. I took out the camera, put it on the tripod and turned it on. It didn't come on. It didn't come on?!!!

"OK, dont panic," I thought to myself. I took out the battery and then put it back in. Nothing. I looked for ice on the contacts, tried a different battery, tried warming the entire system in my sleeping bag. Still nothing. Now I began to panic! Here I was, in literally the most remote place I had ever been which had taken the most time and expense I have ever expended to reach, on the second night of a two week backpacking trip as a professional photographer and I had NO CAMERA! After three flawless years of devoted service, my Canon 1Ds III would never come on again and today it sits in Canon's repair facility. Obviously, I could not have taken a back-up due to the weight constraints of such a trip. I have known mountaineers who had cut off the end of a toothbrush to save weight on similar outings, so another 2-pound body was out of the question. Some good that would do me.

The last picture the 1Ds III ever took, Tombstone camp

What could I do? It's an amazing place and I had just spent two hard-earned days getting there. I had 15 more days in the region before I needed to head down to Washington to conduct another photo tour. I considered yelling, crying, whatever... I just couldn't. It was futile. What good would it do? I simply looked up and stared at the peaks. I couldn't eat dinner. Nothing. I just sat there, trying to grasp the enormity of the predicament and the decision to continue or not with the trip, without camera. I suppose it beat breaking a leg or something. Barely. Of course, a sparkling display of northern lights kicked up shortly thereafter.

At the end of the day, I reasoned, I'm a professional nature photographer. That's what I get paid to do and this trip had already consumed a huge amount of resources and time. I decided I can't be justified in spending the remainder of my days here wandering around without any means to capture the place. I was here just long enough to realize what incredible potential there is, and I will return soon enough.

I spent an incredibly arduous part of two additional days making my way back out of the range, this time electing to maneuver my way across and wallow through a combination of sharp, wind-swept talus slope and deep snow drifts along a high ridge rather than do battle with the willows in the valley again. As I did, the weather kept getting worse. I made it out just in time, as snow was again falling and the wind howling.

At that point, I could have shelled out the $1700 for that helicopter after all and gained quick access back into the range once the storm cleared. But the reality of Arctic winter had set in. Once everything freezes and gets snowed under, finding the type of deep, dynamic landscape images I had hoped for combined with the Aurora were rare if not impossible to find. It was a wind and snow scoured land more bleak than I imagined the surface of the moon to be. There was a very, very short window where one can capture the type of images I'd envisioned and I'd already missed it. Next year, I'll try again earlier in the season. There can't be more than a one or two week window to capture the place the way I had wanted. But at that point, I figured my efforts would be best concentrated in the lower country where the big rivers had still yet to freeze and I might find some trees with new snow on them - anything to give the viewer a sense of both a place of great beauty and the aurora, should I be fortunate enough to capture it.

I returned to the town of Dawson City to wait out what turned out to be several days of snowfall and valley clouds which precluded shooting the lights, while camping in an abandoned-for-the-season campground nearby. I found the town itself to be fascinating - the closest thing to the year 1900 on this continent I had ever seen. Surrounded still by extensive mining claims, as it was in Jack London's day, you simply rounded a bend in the river along the Klondike Highway and there it was.

The only hamlet for more than 100 miles in any direction, Dawson City is home to only one half-paved road and a ferry system that takes folks across the Yukon River in the summer, west to Alaska. There is no point in paving roads or building a bridge when snow and ice are the main surfaces of transportation here. Once the river freezes, people just drive across.

A sign on the general mercantile in front of me read A Store That Sells Most Anything.

"Except, of course, fresh produce this time of year," I thought to myself.

Half the buildings in town seemed to have been abandoned since the Gold-Rush era more than 100 years prior, preserved to some extent by what I figured was a combination of dry, cold climate and what seemed to be a complete lack of interest in renovations by whatever city planning department there was, if such a thing existed.

When I really want to get to know the people of a place like this, I often find a bar. Considering the recent events, a bar was in fact the only obvious choice. To find a bar in Dawson City, one simply has to park - anywhere at all will do fine, and walk over to one. I got the feeling that months of darkness and three quarters of the year in the cold takes a toll even on the locals, who all seem especially fond of drinking in such northerly latitudes.

I wanted to get a feel for the people called by whatever odd purpose to endure here, so I pulled up to a place entitled "The Westminster: Since 1898". Clearly, the building had not been up to code since around 1898, as it was visibly leaning, a good chunk of the backside had simply fallen away, and two thirds of what was once an accompanying hotel seemed to be closed (I later found out it was not, but probably should have been). Nevertheless, there were lights on and the sound of many hearty voices inside at 11 in the morning.

I walked in and sat down. History adorned every nook and cranny of the building, but if you had told me the date was a hundred years prior I would not have known the difference at first, with the only possible exception being the hot-dog rotisserie in the corner. Now that's technology!

There was a sizable gathering of regulars inside, despite the early hour. They did not wait long to gather around and ask this new guy who was here in the middle of October questions and share stories as well. Everyone here had quite a story, it seemed, if not many, many very odd stories. A collection of more eccentric individuals I had rarely encountered. I met the owner, Clive, a Brit who'd been here since 1977 and was already 4 or 5 beers into the morning of socializing with the locals. The wall in front of me was filled with historical pictures of the local happenings (mostly dog-sledding and hunting) and the pictures of long-time patrons of the bar who were now deceased.

Not surprisingly, I managed to be persuaded into spending most of the afternoon there. At one point, a fellow of First Nation's decent (native Canadian, likely Inuit) came in with a large black plastic bad and Clive spotted him immediately.

"You have my moose?" he asked.

"Nothing but the best here," the native responded while opening the bag.

Clive asked me if I'd like some moose meat so I looked in the bag. The moose had probably been killed in the past day or two and hung before being proportioned out. There was some various rib meat and a heart wrapped separately in the bag, soaked in blood of course. It was normal and way of life up there where moose and many other large game animals are in great abundance. It was a striking and even appreciated contrast to our southern disassociation from the process of killing and processing the meat we eat.

"Sure," I responded. I have a background that is significant in the culinary but had never had moose meat, much less from a guy at a bar. I found it to be quite excellent the next day with caramelized onions and a quick demi-glace.

I also met a guy who's claim to fame was that he was said to have once kicked John Lennon as a result of a 1963 tiff involving a female friend after a show in Britain. His age and story made it almost believable. I met another enormously-bearded fellow who arrived in a gutted custom 1970s custom van in which had an installed fireplace and chimney which I assumed he lived in. One of the fellow patrons offered me some hashish while another told me about his former residence in Siberia and how he found the climate here to be comparably tolerable (it can hit -60F in January in the Yukon). They was a mixed bag of highly individual personalities who all assumed I was here on some sort of mining or hunting affairs before hearing of my photographic pursuits. Normally when I describe to the locals the nature of my business and how I'm doing weeks in the backcountry alone and camping just outside town in 0-degree weather, I get looks of half worry and half amazement. Here, they were simply amazed that I was not out hunting too.

I got to know the town a little better over the next week while the weather was nothing but clouds and more clouds. Interestingly, it really didn't snow very much but the sun never really showed up either. Using the supplies I had allotted for my backcountry trip, I had begun to venture off to the foothills of the Ogilvie Mountains (of which the Tombstones are a part) in 2 to 4 day scouting trips to determine what other photographic potential there was to be had should the weather clear. I made my way as far north as Inuvik, near the Arctic Ocean and 150 miles north of the circle. The 22 gallons of extra gas strapped to the top of my rig proved just barely enough to allow me to complete my journey which involved many back-and-forths along the Dempster, a 500-mile gravel and snow road that connects Dawson to Inuvik. All the while, I stopped frequently and hiked along the rivers, trying to find a scene that would work to compliment the aurora. Finally, I did.

The coldest spell of the season was moving in but it was also finally clearing off. I had found a spot on the shore of the northern Ogilvie River where I could look downstream towards a pyramid of a peak and catch both interesting ice formations up front and streaks left behind by the chunks of floating ice which were rapidly thickening. Of course, the spot I needed to be with the tripod was accessed only by precariously balancing on a triangular rock in the river at night surrounded by at least three feet of water on all sides.

I camped nearby and tried to stay up until 9 or so (it had already been dark for hours) but the sky was clouding up again. On account of the clouds, I decided to go to sleep, setting the alarm for 2 hours later. When I awoke, the interior of the vehicle was dimly immersed in a greenish glow from outside that I instantly recognized. I jumped out, looked up, and saw the most impressive display of lights I had yet to see during the trip. I immediately threw on my parka and I was off! Wow! I cannot tell any of you what seeing a show like this is like. No picture you have ever seen or will see can capture one-tenth of the beauty of an aurora. Moving, morphing, and dancing like a brilliant, neon, phosphorescent curtain, it waved vigorously but silently 180 degrees across the sky. There were mostly greens, but also reds, purples and orange hues that came and went too. On a moonless night, the aurora on its own will put off enough light to allow itself to be recorded with short enough exposures to capture it's dramatic, every-shifting shapes and color.

After a short drive and hike, I was on my rock, tripod and camera in hand, capturing the finest of natural spectacles I have ever witnessed. I was so transfixed I lost track of the photography from time to time and just stared, straight up into the night sky. The thermometer read -11F when I arrived and -18F when I left the river four hours later. The cold had not even occurred to me and the time had gone by like it was ten minutes, even despite my balancing act atop the increasingly icy rock. At last, despite the great loss I had felt earlier of not being able to be in my first-chosen and infinitely more dramatic location, I had a shot. And I had an experience I will never forget, totally alone with the fullest magnificence of this natural wonder.

Aurora over the Ogilvie River, Yukon

Now a week since I'd left the Tombstones, defeated by the finite line between the pros and cons of modern technology, I had something to show for the piece of a trip that ended up being 9000 miles of driving (often at over $100 per 300 miles in gas), one of the hardest backpacking trips of my life (from which I was just now fully recovered) and three weeks in length. But with a week left, I was off to find more.

The next night at another spot proved clear as well and a dimmer, but still very impressive show of lights took place. Since at the time of this writing I had not processed any images from my trip digitally, I doubt the rendering could possibly match what I'd enjoyed the previous night. Additionally, I seemed to have exhausted most of the possibilities in the area. Without new snow in the forecast and with even the rivers now pretty much frozen on the Dempster, I decided to go elsewhere to make the most of my remaining time.

I scoured the maps that included the hundred-thousand square miles to my south and east looking for potential. If I'd made one major mistake this trip, it was failure to research a 'plan B', just in case the Tombstones didn't work out. Nothing like trying to determine the photo potential of a landscape from maps in 1:250,000 scale! They're practically useless. I drove down to Whitehorse, Yukon's capital and home to 70% of its 30,000 residents and looked online as well. I eventually settled on another area of the Yukon and Northwest Territories border called the Nahanni Range. I figured I would have to live with trying to find something near the one and only road the goes through that range, so off I went, 22 more gallons of fuel on the roof. One thing about driving this country is how you really get the sense of just how big it is. Going from point A to point B, no matter what the two points of note may be, usually takes at least as long as driving back and forth across my entire home state of Oregon.

I made it down to Watson Lake on the Yukon's southern border and started up one of the most grueling roads I've ever encountered into the Nahanni Range. Just imagine doing an average of 25 to 30 mph in deeply rutted snow on an impressively winding two-lane road in the best of areas for 180 miles, occasionally punctuated by hulking semis barreling towards you unexpectedly every couple hours, which is just enough time to completely forget there could be semis on the road. Once, coming over an abrupt hill, I noticed a semi too late and swerved right into a snow-bank which luckily was sturdy enough to keep me on the road by not so rigid it bounced me back into the oncoming big-rig. I never did figure out why there actually was a road here to begin with. It simply ended without cause, place, or description on my map.

There was one campground with four or five sites along the road that was snowed under for the most part. Being as though it was on the river and next to some of the biggest peaks, I plowed the FJ through the snow and made a site that would be my base for photo scouting. I hiked extensively the next day and found what I thought to be an outstanding composition should the aurora appear. I've found that the secret to these night-time is that they have to feature both naturally luminous subjects (water, snow-covered subjects) and cannot be reliant on fine details. This spot had it all, but again unfortunately, it was cloudy. During my 16 nights at that point, I'd only experienced 4 that weren't cloudy in the mountains. Whether it was a sub-arctic October phenomenon or just really bad luck I didn't know, but I was about to make it 3 out of 4 more, with the only clear night having no showing of the aurora (being 500 miles further south couldn't have helped).

One of the most often-overlooked aspects of doing this type of winter trip in the middle of no-man's land is the psychological effects of being so distant with no connection to anything or anyone for so long. It's perpetually cold and dark 17 hours a day. I had no phone, no power for a laptop, no internet and once I've hiked the immediate area, no gas or reason to go off aimlessly (there are no service stations on the road, so once you've expended your supply, that's it). I sat around and read much of the waking day huddled in either a sleeping bag or parka, never seeing nor speaking to anyone. It makes me question the understanding of people who say they envy what I do. At one point I read David Robert's account of Russian Pomori Sailors stranded for 6years on an island at 77 N latitude in the early 15th century. Reading that, however, made me feel like a wimp.

I finally left the arctic after spending over three weeks of driving, hiking, and waiting, not to mention at least five thousand bucks lighter as well (not including camera repair). All of this for what was, on the surface, basically a couple of photographs. Below the surface though, I gained a deeper appreciation for the people who make their home there. I also learned about the vastness and spirit of the landscapes first hand and saw incredible amounts of wildlife, much of which was new to me. I was fortunate enough to see moose, caribou, Arctic Fox, Ogilives (hawks), ptarmigan, Woodland Bison, Musk ox, grizzly bear, black bear and a lynx, among others.

British Columbia is an enormous chunk of land from north to south. In fact, it's as long to drive across British Columbia from Watson Lake to Vancouver than it is to drive lengthwise across Texas - about 1200 miles. I did it in two days, with a stop over at Hyder, Alaska, in the heart of the Coast Range. The little side-venture ended up being one of the most inspiring parts of my entire trip. I had never been to the BC/Alaska Coast Range before but I now know how much I MUST return! These peaks, only 8-10 thousand feet high, rise sheer from sea level with glaciers pouring all the way down their flanks. The vertical relief itself is simply stunning. The drive to Hyder is like driving through a double-size Yosemite or Zion replica during the last ice age. In addition to its sheer size and ruggedness, the pure, wild, inaccessibility of this range, which stretches for over 1000 miles, is in itself alluring. It was easy for me to see here, only three days drive from my home, some of the greatest and largest untapped photo potential left on the continent, hidden within the world's most glaciated non-arctic mountains.

The next day I made it from Hyder, Alaska to Whistler, British Columbia to meet up with my friend James. Then, after 17 hours of driving, we inexplicably went out for beers. James rents a luxury home right in the downtown area and it was a complete shock to my system. I slept very poorly in his plushy guest bedroom and contemplated a move to my truck. Maybe I had to be broken back into civilization so I could stop home to say hi momentarily on the 25th before starting my Great Northwest Tour on the 26th, where I'd be leading a group of five across Oregon and Washington for 6 days.

I arrived at the Olympic Coast to meet the group on a day with coastal flood warnings in affect but at least the rain was subsiding. Our itinerary was constantly in flux as usual, but the group was supportive and all came away with very strong photo opportunities and a great experience. It was quite a diverse group this time around, consisting of everyone from a broadcasting veteran in his late 60's to a professional MMA fighter in the UFC who does photography because it helps him relax. Seriously!

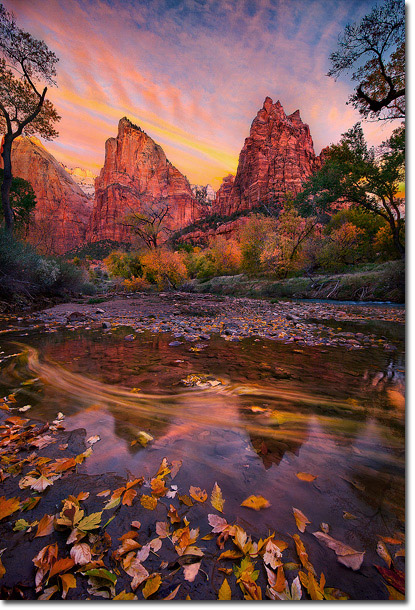

After the NW tour, I had two days to get to Zion National Park in southern Utah where I'd be leading yet more clients. I had driven from the Arctic to Zion in 11 days with a stop to lead a 6-day tour. I had essentially been going backwards in seasons the whole time, from everything being frozen solid to green leaves on the trees! It was 81 degrees on my first day in Zion, 102 degrees warmer than where I camped three weeks earlier.

The third straight month of chasing autumn, Zion in mid-November

I love the Zion region and the SW in general, but the entire time I was not leading a tour down there my desire was to get as far away from people as possible, perhaps in part because of the Arctic experience. There seemed to be more photographers than ever headed for the Park's icons this fall and while that does not diminish them in their aesthetic, it certainly diminishes my desire to photograph them. I don't even want to look like a photographer around other photographers. I'd do trips with my tripod inside my pack so people wouldn't recognize me. I wanted simply to blend in, lay low, explore the place myself and sit down with the rare scene that I was alone with and find a way to capture it. It didn't have to be new or groundbreaking, just away from the crowds. I guess despite my desire to share the wilds with others and teach photography, I find I have to do so on my terms and not be impossibly surrounded by the crowds. I actually had a guy in a supermarket in Kanab come up to me and ask me if I was Marc Adamus, He recognized me from a photo on the web. Such is the age we live in.

Zion is indeed an amazing place. But the way it has become THE focus of nature photography in a region that is THE hub of nature photography for the entire world fascinates me. Whether you're after big cliffs, slot canyons or fall color, I can show you that Zion is equal in any of these aspects to other places within a day's drive that you'll have all to yourself, or very nearly so, to photograph. You'd just think people would spread out and explore a bit more! Isn't that most of the fun? Maybe we ALL need to commit to more vacation time. The fact that the spirit to survive can endure in someone completely sheltered from the natural world for all but a week or so each year totally baffles me.

The one Zion gem that is, in my opinion, truly second-to-none is "The Narrows" on the Virgin River - a 1500-foot deep, 20- to 40-foot wide canyon adorned with fall colors that winds on for over 12 miles. I hiked up there four times the second and third weeks of November after the crowds had thinned out. I learned one thing: Do not hike the Narrows four times without dry-pants in November. Ouch. It was striking as always, though. It is one place I can never possibly tire of that has a beauty completely its own.

As I was driving late at night over sand hills to a remote campsite between Mt. Carmel and Kanab the evening after concluding my Zion tour, suddenly heard a "POW", followed by a "SSSSSSSSsssssssssssssssssss!" Uh oh. The sound was coming from INSIDE the vehicle! I slammed on the brakes, narrowly avoiding a cloud of eye-and-nose-killing pepper mist emanating from the area of my camp-box. Damn! I knew I should have replaced that lost safety on my canister of bear spray! Something had shifted in my camp-box and triggered the sudden release of the whole bottle! I threw everything affected out of the vehicle immediately and took all the water and towels I had and began the cleaning process out on the sand. It quickly proved impossible to be very thorough. I did not use gloves, and that was a huge mistake. It wouldn't be until three days later when I finally got the last of the pepper spray off my hands and ten minutes of scrubbing at a sink the next morning before it was safe to touch my eyes. A more permeating and resilient substance I have never come across, and I can only imagine the torture it would inflict on an animal affected by it. It eventually took several hours, gloves, and a stop at a do-it-yourself car wash in Kanab to clean the remainder of my equipment that I was able to salvage.

Two friends of mine accompanied me for the next leg of my journey, which was no where in particular, just the way I like it. Kory, from Minneapolis and Colin, from Albuquerque usually bring a substantial beer supply with them so I let them tag along. They are both individual shooters as well, so we're not following each other's tripod holes or anything. We were just hanging out for some campsite camaraderie. Still, there's something to be said for being surrounded only by caribou, grizzlies and Musk-Ox, and I think that something is that it forces you to appreciate wildness. In wildness, you gain a much deeper sense of being there - INSIDE the place. When you really understand what it is to know a place on that deeper level, your photographs will reflect that and your most meaningful work will often be the result.

We got away from it all as much as we could. We hiked canyons on the Navajo Reservation and Escalante. We camped out at remote sandstone pockets in the Vermillion Cliffs. Our days were usually spent together in the same areas, yet apart doing our own things. The exception was the gathering around camp at night, waiting for whatever I concocted for dinner out of the back of my truck, which I hope would put any of the nearby restaurants to shame. We spent our last night on Utah's indescribably beautiful Boulder Mountain, a place that has an energy all its own. I'd passed through this area many times. This place has a way of totally captivating those who take a little time to explore it but none of the traditional ways I photograph really seem to have captured something of its essence. I was reminded of Bill Neill's "Impressions" collection of work involving camera motion during the exposure and spent the next two hours captivated by making images that offered the viewer mere glimpses of the subjects hidden in the landscape blurred by streaks of luminous colors. Its as if I was creating an impressionistic painting with my camera. I was satisfied with the results - something real, but also something hidden in the magic cast about the scene.

I still had my sights set on a few more photo projects before I left the Southwest which I was looking forward to even more now that snow was in the forecast across the region. First though, I took a couple days to visit and hike with some good friends, Guy Tal and Floris Van Breugel, both whom I admire greatly as both people and photographers. In my opinion, two individuals with a better eye for interpreting and capturing the softly-spoken beauty and hidden gems within the natural world have never lived. We toured and hiked some canyons in Guy's area near Torrey, Utah before departing for Zion. There, Floris and I parted ways on a morning where snow blanketed the valley floor, a stark contrast from the 80-degree weather I had arrived to see three weeks earlier.

I followed the snowfall from Zion to Moab later that day, which isn't uncommon in my own style of photography. I love those rare moments of light and unique conditions, such as a clearing snowstorm on the desert and I will do whatever it takes to pursue them. Although I appreciate the intimate scenes as well, but the grandest of the landscapes is what compels me to frequently travel great distances. I was once near Phoenix and spotted what looked to be promising clouds moving in over Moab, over 8 hours away, on a hand-held weather satellite over my phone. Of course I went for it. I took into account a recent rain I had heard about in Moab knowing it would have filled some potholes that could reflect some of the sandstone towers and might benefit from colorful skies. This is often what landscape photography for me is all about - pre-visualization. It's not always about what's there, but what could be and the anticipation of it, wherever it is.

Skies, atmosphere and any kind of dramatic weather have fascinated me for as long as I can remember and have no doubt greatly contributed to every aspect of my appreciation for nature by simply beckoning me to get out there. I wasn't normal at 8 years old either: waking up to record weather data from various cities around the United States. So it's not surprising in the least that my photographic art has taken the fullest advantage of the most interesting weather I can find.

Today, I really don't feel the need to be always connected to the goings-on through modern technology like smart phones, but I will say that for someone who spends up to 300 days per year on the road or trail, they are virtually a necessity at times if your desire is to stay in business. I use my phone most frequently to track the weather - mostly NOAA forecast discussions and satellite imaging. To use and really understand these modern tools of weather forecasting plays a huge role in my photography today so it's surprising to me the great number of landscape photographers who simply look at a forecast and make guesswork out of it.

Technology has a price though, as I would find out once again after a few days spent in the Moab area photographing the spectacular Fisher Towers. Now my Canon 5D Mark II started failing me. First it wouldn't recognize the remote release and then it wouldn't recognize one of my batteries. The next morning it couldn't recognize any of the batteries or turn on at all. Damn. I've never dropped it or even gotten it wet and it had seen at the very most, 30 days in the field. I'm afraid I cannot speak very highly of Canon's cheap build quality on this model, which I use to back-up my also-deceased 1Ds III.

It was the first time in my career that I can recall a camera simply failing without any justifiable amount of use or abuse. In the past, I had swam out of Oregon's Eagle Creek (after falling in) with camera totally submerged but still in hand. I've run-over my own camera bag and snapped the lens off a Canon 5D. I have had my whole set-up topple over in wind and land on hard granite and I have been hit and knocked down by huge ocean waves using my 1Ds III. None of these events had ever resulted in the complete malfunction/loss of a camera body, but within a month of using the 5D II, I just watched the thing slowly fall apart. Canon ought to realize the price race with Sony should not also be race to sacrifice build-quality. Right now I'm really fighting the urge to begin rant on ultra-light outdoor gear.

I did take in some good shots from the Towers prior to the untimely demise of my equipment, but with a day prior to Thanksgiving, I decided it was best to leave the rest of my ideas for here until spring. I left the off-road Jeep capital of the world on a very rare 0F degree morning and headed back through Salt Lake on the holiday and eventually settled on a campsite near Nevada's Ruby Mountains. On the BLM lands across the western US, which consume 80 percent of Nevada, to find a campsite one simply needs to drive off the paved road and park. Never satisfied with being even remotely near the paved road, I drive off through the snowy fields and right into a 3-ft. drift of powder snow and came to a stop. Totally stuck. Whoops. So that's why I couldn't see any sagebrush there.

FJ on the high Nevada desert

Being stuck in remote areas in deep snow can be intimidating if it hasn't happened to you a hundred times before. I've learned to dig/cut/jack my way out of anything and could probably sit down to write a book on the times I have freed my vehicle from similar unfortunate predicaments. I simply went up on my roof, grabbed my snow-shovel and an hour later was cooking dinner. The -18F temperature the next morning was refreshing as I brewed fresh-ground coffee outside, although it was very cold even by any high-desert standards in winter. Luckily, the truck started and I was on my way home.

Although adventures in the wild and open are my first love, only recently since the birth of my 2-year old son, Galen, have I ever found an equal appreciation in anything human. To see him for only part of a day between travels is really hard on me. But now that I'm sitting here, working from home with more than two months before I'm in the field again for more than a few days at a time there is no greater joy in my life than to spend time with him. It is something truly amazing, the connection we have with our own children. It's above any possible level of understanding among those who have not experienced it. I want nothing more than to give him every opportunity I can to grow, learn and experience the beauty in the world that I have found and that he will find himself. I can only hope and imagine the adventures we may share in throughout the years to come.

Comments on NPN nature photography articles? Send them to the editor. NPN members may also log in and leave their comments below.

Marc Adamus is a landscape photographer based in Corvallis, Oregon. The visual drama and artistry of his photographs are born of a keen eye for the many moods of Nature and a life-long passion for the wilderness. This passion shines throughout Marc's work and has attracted a wide audience around the world.

Marc Adamus is a landscape photographer based in Corvallis, Oregon. The visual drama and artistry of his photographs are born of a keen eye for the many moods of Nature and a life-long passion for the wilderness. This passion shines throughout Marc's work and has attracted a wide audience around the world.

Marc's style is unmistakable. His talent for rare captures of amazing light and fleeting atmosphere imbue his portfolio with a sense of the epic, majestic and the bold. His success derives from patient single-minded pursuit of all the unique moments that generate the magic and energy of the wilderness, often spending months immersing himself in the landscape he shoots despite the rigors of season and weather. More of Marc's photography can be viewed at his website, www.marcadamus.com.