A lot has already being written about the “art of composition” – the rules and the guidelines; the critical must-dos and absolute no-nos. But how does one apply those great advices and holy grails of composition in the field? One can argue that no seasoned or professional photographers are actually thinking of those rules and guidelines when they are making their images. All those just come as a natural second habit, just like we don’t need to read the owner’s manual every time we drive our cars.

So how does the physical process actually work that takes all the wisdom of the “Art of Composition” and applies it in the field? I call it the “Act Of Composition” – and pardon my bad sense of humor.

First, lets revisit quickly the ingredients of a good photograph: good composition and good light. However, for a great, memorable photograph, you need something more than those two things: a “wow” factor – which is probably how a good composition interacts with the right light to evoke emotional feelings in viewers’ mind.

Lets keep it simple for now as we think about a good composition. I will argue that a good composition can be broken down into good subject and good design. A good subject does not always ensure a good composition, otherwise all the images of the Grand Canyon or Taj Mahal would be masterpieces. However, a good design can make even an ordinary subject really interesting. And more importantly, a good design is the only thing that is completely under control of that crazy-looking, gadget-laden guy - the photographer. Have you ever seen a bunch of tourists wondering what that guy with the funny looking vest and rocket-launcher-sized camera is trying to do by lying low on the dirt or leaning dangerously over the cliff? If not, you missed the fun or perhaps you were too engaged in composing your images.

What I have noticed from my style and by watching other seasoned photographers in action is that finding the right composition is never a slam-dunk. It’s rather an iterative process, refining where you stand, how high is your tripod (or hand), what angle the camera aimed at, what lens is on the camera, etc. There are many such decisions, which never come together at the first attempt. Borrowing from a basketball analogy, it’s like making a dozen or more passes from half court before finally taking a shot at the basket.

The most critical part of the whole process actually happens before it physically starts - with pre-visualization. When you see a scene, something tells you inside your brain, “I like this and I am going to photograph it.” But it’s wise not to rush with that emotion, but stop there for a moment and think, “Why do I like the scene? What do I want to show and convey through the image? What are the ingredients that I need to include to accomplish that?” The answers may not be always simple and singular. For example, you may like a number of aspects of the scene and want to show a number of objects in the final image. That’s fine. There may be more than one image possible from that same spot, all with different moods, emotions and messages.

Then starts the actual physical process: often intense, sometimes acrobatic, and almost always funny for someone who cares to watch. You might choose a foreground, but those branches and leaves somehow manage to invade the frame. You lower the tripod, but that distant mountain seems to hide behind some weird-looking boulders. You change the lens, but where the heck is the polarizer for this one? Finally, you get it. “Ahh...perfect.” Hopefully, the light will hold, or even better, you wait for the light. It may be seconds, minutes, or hours. To quote James Lalropui Keivom, ”It's weird that photographers spend years or even a whole lifetime, trying to capture moments that added together, don't even amount to a couple of hours.”

But that’s not the end of the story. Often when you capture that perfect composition from a spot and think you are done, something always bothers you inside and rightfully so. You’ve probably not checked all the other options. Maybe there was another superb composition that you have yet to consider. The light is still good so you go back to work again trying to find another perspective, another vision, another story, another beautiful design of elements within your little viewfinder that exceeds all the images you have taken in that location. Sometimes the effort pays off and you make stronger images. Sometimes it’s all frustrating and waste of effort. Maybe that the first composition was the best one and nothing works after that. I like to call that “diminishing returns of continuous effort”. But nevertheless, this is a very important part of the creative process. How do you know that you tried your best to unlock the full potential of a scene, unless you actually tried?

My intention for this essay is not to describe any rules about the act of composition. I just wanted to share some observations and guidelines as we analyze and learn from what actually happens when a photographer tries to find the best composition – with almost the intensity of a hungry tiger approaching its prey. Ultimately, it is that hunger for the best possible composition that is vital for the photographer to keep going.

“It is not the knowing that is difficult, but the doing” (Chinese Proverb)

But the good news is this: after having more experience with your equipment, gaining a deeper knowledge about the subject, and spending more time in the field, the “doing” part does get more productive, if not easier.

To illustrate the key points that I made so far, I will use a few images of mine.

The first image is an example of pre-visualization. I camped within one mile of this particular location during a backpacking trip through Peruvian Andes and scouted this exact spot the evening before, guessing how the morning alpenglow would appear and planning how I would want to use the compositional elements to capture the very essence of the landscape.

The second image is a product of set up and then a rigorous refine-improve-tweaking iterative process. During an hour or so in this location in Valley of Fire, Nevada, I shot at least 50+ different images while incrementally improving and experimenting with compositions until I was satisfied with this one that really captured the true character of the place.

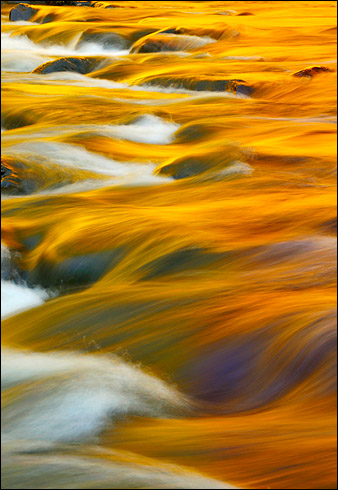

The third and fourth images are examples of staring over and finding something new: when you think that you have found the “perfect” composition, but another stronger or equally superb composition waiting just nearby. I took these two shots within 100 yards of each other during the short period of time when the light was cooperative. I was happy with the first shot but just did not give up and was rewarded for the perseverance with the second. This does not always work out, but you never know until you try. Don’t just be satisfied with a single composition from a spot, however good you think it is.

Comments on NPN landscape photography articles? Send them to the editor. NPN members may also log in and leave their comments below.

Arnab Banerjee lives in the lower Hudson Valley of New York. His love of photography and nature is a long time affair and has evolved through many mountaineering and exploration trips to various mountain ranges and wilderness across the world. By profession, he is a business strategist but he spends the rest of his time trying to make evocative and unique nature images, bringing him close to nature. His writing and images have been published in many journals. More of his work can be seen at his website, http://www.arnabbanerjee.com