|

|

Philosophy and the Art of Photographing Torres del Paine Photography and Text Copyright Joe McDonald ďWhy are you going there? Will you get anything that you can sell?Ē I was asked these questions more than once when photographer friends learned I was going to Torres del Paine National Park in Chile. For anyone familiar with Torres del Paine, asking why someone would want to go there is a non sequitur. The southern Andes and the Patagonian highlands are so beautiful, the area has to be considered one of the must-see destinations for photographers who have an urge to travel. Ever since Iíd seen the first images produced in Torres del Paine Iíve hoped, one day, to have the chance to visit. Would material sell? I didnít care. That answer might surprise some, for one would think that a professional nature photographer would be motivated by sales. And while I certainly did hope to produce many salable images that would justify the trip, that wasnít my reason for going. Like a climber that confronts Everest and is asked why, my answer was the same -- because it was there. To capture itís grandeur, to experience the ever-changing weather, to endure the blow-your-hat off winds, to simply be there and to celebrate that opportunity through photography was reason enough to want to go. In considering my first article for NPN, I wanted to extol the wonders of Torres del Paine. I was excited and enthused by the images Iíd made; I was thrilled by the experience, not only in photographing landscapes, birds, and mammals, but also by the life-experiences I did not capture on film. But I also wanted to introduce my personal shooting philosophy, shared by my co-columnist and wife, Mary Ann, in a forum thatís dedicated to the joys and delights of this craft, this art form. For photography to us is an art, and the act of shooting is, quite honestly, our attempt to pay homage and to celebrate that which we treasure most Ė the wonder and beauty of nature. If our shooting appeals to a buyer, fine, but neither Mary nor myself are solely motivated by the market. If we like something we shoot it. If itís a salable subject and the lightís great and the image dramatic, we might shoot a lot of a

That said, Torres del Paine offered the potential of a lot of salable images. Located in southern Chile, not too far from the Pacific and the cold Humboldt Current that hugs the west coast of South America, Patagonia is a land of ever-changing weather. Hosted by two long time Chilean friends, veterans of some of our photo workshops and tours, our trip was timed to coincide with what was, statistically, the optimum time to visit. And weather is important, for like Denali in Alaska one can visit this park and never see the grand horns and towers that make these mountains so distinct. Indeed, my friends had, on two previous visits, only brief glimpses of the peaks between bouts of almost constant rain. This time statistics, and luck, were with us, and in our entire week in Torres del Paine we experienced only a few brief showers. Of course, some of these were driving, horizontal sleet and hail storms that stung cold cheeks and temporarily cloaked the low shrubs in a veil of white, but no precipitation lasted more than an hour. One does not hope for consistently clear blue skies when photographing in Torres del Paine. Indeed, it is the dramatic weather that produces some of the most dramatic images, when clouds temporarily shroud a peak or mountain slope, when early morning light suddenly bathes a slick granite rock face, or when a God-beam shaft ignites a lake in silver fire. Bluebird weather doesnít produce that drama.

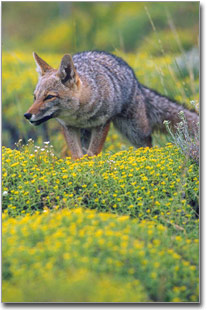

Built like a slender, wiry, tawny-colored llama, the guanaco might not seem to be the most exciting wildlife subject. But wild guanacos are animated, and in early December, the time of my visit, babies were birthed and nursed, couples mated, and rival males battled over harems. The latter was particularly exciting. Rival males would chase one another, occasionally stopping to rear on their hind legs and box before one turned tail and galloped off, sometimes screaming and squealing as his pursuer snapped with sharp incisors at its unprotected haunches. We saw many fights, and more chases, with some males pausing close a moment, puffing and spitting blood before charging off after another potential rival. The other reasonably common mammal is the Patagonian gray fox, an animal that closely resembles our North American gray but belonging to an entirely different genus. We saw several and all were rather tame, but some were laughably so. Foxes have learned that hanging out at some of the pull-outs and viewpoints is a great way to get food, for almost every tour bus that stops provides a couple handouts. When I saw my first fox at a pullout I jumped out of our vehicle and grabbed a 500mm, but within seconds I switched to a 300mm, and then, as the fox trotted close, I grabbed my 35-350. Itís rare to have a chance to use a short focal length lens on a wild mammal, and I was thrilled not only at that opportunity but to have the splendor of the Torres del Paine massif as my background. Because of their elusiveness or wariness most mammal photographs are made with telephotos, where the limited angle of view and shallow depth of field not only isolates a subject but also restricts oneís sense of the animalís habitat. In

I used my wide-angles a lot, but I also used every lens I carried with me, as well as those lenses my friends had brought along. Usually I make a personal vow to use all my gear at least once on any trip, reasoning that if Iím going to bother to carry it then, darn it, Iím going to use it, too. Torres del Paine lent itself to a diverse, unlimited shooting style, and I canít think of another location where I so consistently used every lens at my disposal. I carried two tilt-and-shift lenses, the 24mm and the 90mm, which I sometimes combined with an extension tube or a converter. I used them often, especially the 24mm which enabled me to incorporate a powerful foreground center of interest with the iconic towers and horns of the mountain background. While I usually avoid using filters out of sheer laziness, I used both my polarizers and my graduated neutral density filters quite frequently. I like the two-stop gradient best, as it usually still left a one stop, natural-appearing difference between landscape and sky. Shooting with digital composites in mind I also shot some scenes at two different exposures. Keeping the frame precisely the same for both shots Iíd expose one image for the foreground and another for the background. In Photoshop itís fairly easy to combine the two into one perfect image. This technique, by the way, is especially handy when a background consists of jagged, irregular mountaintops that no graduated filter can adequately cover. For landscapes, a long lens may not be necessary. I think a photographer could get by with a sharp 70-200mm lens with converters, or a 35-350mm like the one I had as a backup. Luckily I did, for on the first day out I discovered that my 70-200 was frozen at the 70mm mark! Not really knowing what to expect, and hoping to film some wildlife and birds, I had brought a 300mm F2.8 along, and I used it, with converters, on several occasions to shoot wildlife portraits. One of my companions had a 500mm along, and that proved invaluable for birds. I saw one puma, and I was incredibly close to the animal, while on foot and perhaps for as long as thirty minutes. Having that experience alone was enough to draw me back to Torres del Paine, and Iím hoping on my next trip to capture one on film. So Iíll definitely bring a bigger lens next time, maybe even my 600mm F4, which would also come in handy for the buff-necked ibis, red-gartered coots, Southern lapwings, Coscoroba and black-necked swans, and Andean condors that I saw on multiple occasions. A long telephoto could also be handy for telephoto extractions, or for panorama stitches of distant landscapes performed on your computer when you return home.

For my money Iíd say mid-December is the optimum time for a visit. The weatherís the best, flowers are out, birds are nesting, and guanacos are exhibiting their most diverse behaviors. While itís usually windy, at least in exposed locations, itís not cold, and a light pair of jeans and a couple of layers of shirts, sweaters, and a windbreaker on top was sufficient for my visit. Torres del Paine can easily be reached in just two days of travel, especially if you fly from the US to Santiago and connect directly with a flight to Punta Arenas where youíd spend the night. Itís only a five hour drive on reasonably good roads from Punta Arenas to the park, unless, of course, you detour to a large Magellanic penguin colony thatís along the way. I shot approximately 50 rolls of film in my five days in the park, and probably too many of those on the enticing guanacos. Will I sell any images from this trip? Probably. Do I care? Depends, there may be bills to pay you know. But that wasnít my reason for going, and even now as I plan next yearís trip it is not the reason Iím longing to go back. Being on-foot when I wished, having animals close and unafraid, having that specter, the puma, ambling along a game trail beside me, and being nearly over-whelmed by the sweeping beauty of the landscapes, thatís why Iím returning. Joe and Mary Ann - NPN 020 Comments on NPN nature and wildlife photography articles? Send them to the editor.

Joe has been a full-time nature photographer since 1983, and Mary since 1989. They have led photo safaris to all seven continents, and spend as much as 20 weeks per year in Africa. Their work has appeared in every major natural history publication in North America. Joe is an active member of the Outdoor Writerís Association of America and a former board member of the North American Nature Photography Association. Mary is a first place winner in the BBC/BG and Natureís Best photo competitions. Joe and Mary maintain an active website that offers many features, including tips and questions of the month, a viewerís gallery, product reviews and links, and trip reports and portfolios. Complete photo and digital course and photo tour descriptions are available on their website, www.hoothollow.com. |

|

|

particular subject. But we do not photograph just to attempt to make money. In todayís competitive marketplace, if we were motivated solely for those reasons weíd be doing a far more lucrative form of commercial shooting. We shoot what we love to shoot and, hopefully, the money, or some money, will follow.

particular subject. But we do not photograph just to attempt to make money. In todayís competitive marketplace, if we were motivated solely for those reasons weíd be doing a far more lucrative form of commercial shooting. We shoot what we love to shoot and, hopefully, the money, or some money, will follow. However, Ďgoodí weather, with clear blue skies and little wind sure has its merits. While southern South Americaís terrestrial wildlife is rather limited, favorable conditions make using a long telephoto much easier, at least if youíre hoping for sharp images. Two species of mammal can be expected, and one of these, the llama-like guanaco, is abundant. Guanacos are distantly related to camels, and are the only one of four species found in South America that is truly wild.

However, Ďgoodí weather, with clear blue skies and little wind sure has its merits. While southern South Americaís terrestrial wildlife is rather limited, favorable conditions make using a long telephoto much easier, at least if youíre hoping for sharp images. Two species of mammal can be expected, and one of these, the llama-like guanaco, is abundant. Guanacos are distantly related to camels, and are the only one of four species found in South America that is truly wild.  Torres del Paine, that wasnít the case, either for the fox or for the guanaco, which I framed against snow-covered peaks or classical spires on multiple occasions.

Torres del Paine, that wasnít the case, either for the fox or for the guanaco, which I framed against snow-covered peaks or classical spires on multiple occasions. For anyone considering a visit to Torres del Paine my first piece of advise would be to just do it. Youíll love it. The park is good from November at least until April, although tourism increases after Christmas. Remember that seasons are reversed in the southern hemisphere so November marks the beginning of Spring and March through early April is their Fall. The park is open in winter but a heavy snowfall could close the roads for several days. Park roads arenít plowed, and although the snow doesnít last long, being marooned inside the park could be a hassle if you have a flight home to worry about.

For anyone considering a visit to Torres del Paine my first piece of advise would be to just do it. Youíll love it. The park is good from November at least until April, although tourism increases after Christmas. Remember that seasons are reversed in the southern hemisphere so November marks the beginning of Spring and March through early April is their Fall. The park is open in winter but a heavy snowfall could close the roads for several days. Park roads arenít plowed, and although the snow doesnít last long, being marooned inside the park could be a hassle if you have a flight home to worry about. Joe and Mary Ann McDonald conduct photo and digital workshops at their home in Hoot Hollow, Pa., and lead photo tours and safaris around the world. Joe is the author of 6 books on wildlife photography and 1 on African wildlife; Mary is the author of 29 childrenís books on natural history. Joe is a columnist for Outdoor Photographer Magazine, and Joe and Mary are columnists for photosafaris.com and Keystone Outdoors, and field correspondents for Natureís Best Magazine.

Joe and Mary Ann McDonald conduct photo and digital workshops at their home in Hoot Hollow, Pa., and lead photo tours and safaris around the world. Joe is the author of 6 books on wildlife photography and 1 on African wildlife; Mary is the author of 29 childrenís books on natural history. Joe is a columnist for Outdoor Photographer Magazine, and Joe and Mary are columnists for photosafaris.com and Keystone Outdoors, and field correspondents for Natureís Best Magazine.