Rethinking Talent |

1 - Introduction

I have no special talent. I am only passionately curious. - Albert Einstein

I am often asked about the role that talent plays in the creation of art in general and of Fine Art Photographs in particular. I have to say that, honestly, I do not like this question very much. Why? Because underlying this question is the assumption that talent is something innate, something that you either have or do not have. Behind this question is the assumption that some people can create art while others cannot, the assumption that those who have talent can create art while those who do not have talent cannot.

This assumption is based on the belief that those who have talent do not have to work at creating art, or at doing whatever it is that they are doing well. Instead, they can magically tap in a source of innate knowledge that is within them, tap in a well of talent if you will. On the other hand, those who do not have this well can work as hard as they can but, unfortunately, they will not reach success and will not be able to create fine art photography.

The problem with this assumption is that when you believe in it, finding out if you can or cannot create Fine Art Photographs becomes reduced to finding out if you have talent or not. If you do have talent, then you are going to create great work. It is simply a matter of getting started, of purchasing the necessary equipment and of getting proper guidance in the form of books, tutoring, workshops or other learning venues.

If you do not have talent, then you might as well quit right now because you will not find success, no matter how hard you try and regardless of what equipment you use, which books you read or which teachers you study with. Success is simply not possible because, well, you do not have talent.

2 – Rethinking Talent

I believe that every person is born with talent. - Maya Angelou

As I said, I do not like this question. But I wasn’t sure why I did not like it until I put it to the test and scrutinized what is involved when we talk about talent. In other words, I was not sure what was unsavory about this belief until I considered carefully what talent is and until I engaged in rethinking talent.

To rethink talent I went back to my own artistic education and asked myself what role talent played in my artistic career. I decided to use myself as the subject of my study because, after all, I know more about myself than about any other artist. I also have access to my early work, work that I have not shown until now. I would not have had access to such work if I had studied the life of other artists.

I started by looking back at the earliest “works of art” that I created, and because we are talking about photography, to the earliest photographs that I took. I was fortunate to have kept those, for whatever reason, and I was fortunate that somehow they made it from France to the US, even though I do not remember packing them.

Let me cut to the chase by saying this: it was a humbling experience. Memory distorts things they say, and in this instance I have to agree with this statement. While my memory of these photographs was “romantic” to say the least, the evidence said otherwise. The fact that I was looking at them about 35 years after they were taken allowed me to take a certain critical distance because I could look at them differently than if I had made them just a few days ago. In some ways I was able, for a short time, to see them as someone else’s work. Not for long mind you, but for some time, and that time was enough.

It was enough to see that these first photographs, which at the time I considered important enough to be printed, were nothing to write home about, to use a popular metaphor. But the fact is that at the time I took them, they were reason enough to write home about. I was proud of them, I thought greatly of them and I believed they were the result of talent.

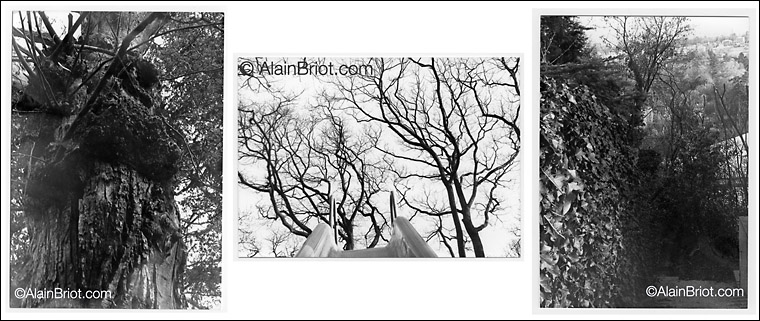

My first three photographs

These images are scanned prints. The original 35mm film was lost and I am fortunate that these 3 prints survived. I have no idea what else was on the film, but from what I remember many photographs were totally underexposed. Also, the film had not been properly developed and fixed. Part of the film was only partially developed, and part of it had been damaged by fixer left on the film because washing had not been done properly. These three images had to be the ones that were printable. All three were taken in a public part located near where I lived at the time. From what I remember they were the first three images on the roll of 35mm film, or at least the first three printable images. As I said, many frames were greatly underexposed and virtually blank.

3 - Let’s Go Back A Little Further

Motivation will almost always beat mere talent. - Norman Ralph Augustine

I took these three photographs with the first camera that I purchased with the intent of creating fine art photographs. This camera was an Exa 500 with a screw-mount 50mm lens and a focal doubler. This setup effectively gave me a 50 and a 100 mm lens. I thought the world of it at the time, not realizing that it was in fact very limiting since I did not have a wide angle lens or a real telephoto.

The Exa 500 was my first single lens reflex and my first 35mm camera. It was also the first camera that I bought. I bought it used, from a classmate and for a small amount of money, but I bought it myself and that was what mattered most. Prior to the Exa 500 I had been given various cameras, including a Polaroid Land Type 80 and a folding Zeiss Icon camera, somewhat of an antique, but while I had fun with these cameras I never attempted to take more than family or souvenir photographs with them. My parents also owned a Kodak Box camera, but again in the rare instances that I used it I never attempted to do more with it than record family scenes.

The Exa 500 was different in that it was to be used for creative purposes, not just for recording things. The time that I acquired it was also important. I was enrolled as a student at the Academie des Beaux Arts at the time, and my primary occupation was the study and practice of drawing and painting.

The Exa 500

4 - Talent And The Beaux Arts

Talent without discipline is like an octopus on roller skates. There's plenty of movement, but you never know if it's going to be forward, backwards, or sideways. - H. Jackson Brown

Interestingly, talent considerations were not really part of the Beaux Arts curriculum. Certainly, we talked about “talented artists” but teaching was centered around technique and practice, not around nurturing talent. Although I did not give much thought to this at the time, in retrospect I can see how this teaching approach was implemented in the school’s approach to teaching art. Acceptance to the Beaux Arts was based on successful completion of a week-long entrance examination, an examination so thorough that preparation for this exam required attending a private school of drawing and painting for a year. Certainly, any student could present himself at the Beaux Arts Exam without having attended a preparatory school. That is, attending a preparation school was highly recommended but not required. However during the 5 years that I studied at the Beaux Arts, I do not recall a single instance in which a student successfully passed the entrance exam without previously attending a private school to prepare for the week-long test.

The test was that hard, or that thorough, as you prefer to put it. One can certainly ask why, especially in light of the fact that, after all, we were “just” painting and drawing, activities that, if one believes in talent, are supposedly essentially talent-based. The answer is that the school board approached entrance to the Academie des Beaux Arts the same way a school board for a technical school would approach entrance to their Academie, college or university.

5 - About The Beaux Arts Entrance Test

However great a man's natural talent may be, the act of writing cannot be learned all at once. - Jean Jacques Rousseau

In other words, the Beaux Arts school board approached acceptance to the Academie des Beaux Arts seriously and with great rigor. The entrance test was taken over a one-week period during which prospective students were tested on their ability to draw and paint the gamut of classic art subjects: portraits, still life, nude, landscapes, etc. There were two tests per day, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. All tests were timed, the timing based on the type of subject matter and drawing or painting type. From what I remember most tests lasted about an hour, although some were longer. Some tests were done in testing facilities, for lack of a better word, meaning there were scheduled outside of the Beaux Arts. Some tests were done at the Beaux Arts, essentially because they would have been challenging to offer elsewhere, either because they involved the use of a displayed subject (a still life for example) or a model (a nude for example). For each subject we were tested on both the ability to draw and to paint this subject, painting being done in the morning and drawing in the afternoon, or vice versa, of the same day.

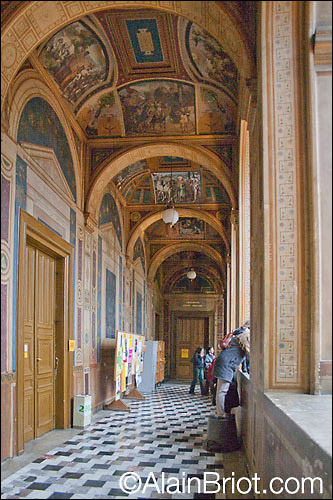

The main entrance to the Academie des Beaux Art in Paris

After this week of testing our scores were calculated, and once that was done the last part of the test was scheduled. This last part, which was done in person, consisted of presenting our portfolio to a review panel consisting of a group of teachers essentially composed of the teachers we would be studying with the following year if we were accepted. Our portfolio consisted essentially of work created during attendance to the preparation school, although it could also contain personal work done outside of the school. The portfolios were “raisin” size, meaning approximately 20” x 25” and filled with about 25 different projects, drawings and paintings done on sheets of art paper.

The portfolio presentation was essentially silent, with us showing our work, pausing a minute or so between each piece to give review panel members a chance to evaluate each project. Members of the review panel could ask questions, and if so we had to answer as best as we could. Once the presentation was completed we were asked to leave our portfolio with the review panel so that they could refer to it later on if they needed to.

We were informed of the final outcome of the entrance exam a couple weeks later. In my case, I learned that I failed the exam. I failed despite the fact that I studied for one year to prepare for the test, I failed despite the fact that all I had to do was draw and paint for a week, something I had done pretty much all my life, and I failed even though most people I had told about this test believed that no one could fail such a test if they were talented.

I was left with the overwhelming feeling that talent was not all that it was supposed to be. I was left with the feeling that talent was way overrated.

Yet I did attend the Beaux Arts the following year, thanks to the last part of the test which, as I mentioned, consisted of us leaving our portfolio for further review if necessary. One of the teachers had been particularly impressed by the work in my portfolio, and exerted their right to accept me on the strength of the portfolio rather than solely on my test results. Certainly, the tests results were considered, but they were not the only deciding factor in that instance. I was in, left to ponder if my poor results on the test were caused by “testing phobia” a supposed inability to perform at one’s peak under controlled conditions, or if my portfolio somehow was inspired by something that wasn’t present in the test, or if I had simply been fortunate to impress the right person at the right time. However, regardless of how I put it together in my head, it just seemed that talent did not play much of a role. How could it? If it had, then I should have been able to pass the test without any preparation, without having to spend one year getting ready for it.

Instead, I had spent a full year preparing for a specific test, I had been an assiduous student, I had attended school regularly, I had received good grades and good evaluations from my teachers, and I had assembled a portfolio of my work as I was asked to do. Yet, I failed the test, and if it wasn’t for a single teacher on the review board, I would have been out, having spent a full year for nothing. Talent, based on my experience, was overrated.

Hallway inside the Beaux Arts

6 - Where does this leave us?

Talent is cheaper than table salt. What separates the talented individual from the successful one is a lot of hard work. - Stephen King

How does this play out in the context of using my first camera, the Exa 500 that I mentioned earlier on, and in finding out that my first photographic attempts were disappointing? Shouldn’t I, at that time, have been aware that talent was overrated and that I should not expect stunning results at my first attempt working with a new medium?

If the process of creating art, or trying to create art, was logical, I certainly should have expected less than stellar results. However, the process of creating art is far from logical. Instead, this process is emotional and cares little for facts and evidence. Even though, by the time I acquired my first camera, I had failed a test that many believed was essentially based on talent, I still had not fully comprehended, if at all, the implications that this failure had. I still believed that I could pick up a new tool and create art, just like that, without study or practice.

Plus, it was photography we were talking about, and after all I was studying painting and drawing at the Beaux Arts, so how hard could it be to take a good photograph? Painting was difficult. Drawing was difficult. Both rely on skill and knowledge and do not get any help from a machine. But photography, which is done with a machine, had to be easy. After all, as several of my art teachers told me, “photography is for those who cannot draw”.

Armed with these beliefs it is no surprise that my expectations greatly exceeded my abilities. Neither was it surprising that the outcome of my photographic “efforts” were disappointing.

But I was not to be discouraged easily. If photography proved challenging, it must be because my lack of technical knowledge is preventing me from reaching my full potential. I therefore proceeded to purchase a technical manual of photography and to read it cover to cover. Once I was done, something that took nearly a month due to the amount of subject matter I had to go over, I knew everything about f-stops, shutter speeds, ISO, depth of field, focal length, focusing distance and filters. Filters were particularly intriguing to me because they affected tone and color. Filters explained why, or so I thought, the photographers I admired achieved certain tones and colors that I could not achieve myself. It had to be the filters, or so was my belief at the time.

However, my results did not improve because I learned how to operate my camera or because I used filters. Certainly, I was now able to use filters, select shutter speed, ISO and f-stop knowledgeably instead of simply placing the viewfinder light meter needle in the center of the white circle. Unfortunately, none of this was enough to create interesting photographs.

What I lacked was the knowledge of what makes a good photograph. However, I did not know that.

I proceeded to upgrade to what I thought to be a better camera, an Olympus OM2 and to invest in lenses ranging from wide angle to telephoto. Surely, having a full collection of focal lengths was going to make a difference. However, while I now could frame a scene in many ways, from wide to narrow and everywhere in between, this alone was not enough to make my photographs more interesting.

In my search for answers about how good photographs were made, I discovered the work of Ansel Adams, Edward Weston and other West-Coast landscape photographers who worked in large format. Their work departed sharply from the majority of the photographs that I could create in a city environment and I became fascinated by the landscapes they were representing.

To make a long story short I acquired an Arca Swiss view camera, a 90mm and 210mm Rodenstock lenses, a bag bellows and a tripod. Equipped with what I considered to be superlative equipment at the time, I departed for a 6 month journey through the southwestern United States. In the suitcase I used to carry my view camera I had packed a copy of Adams’ book “The Polaroid” because I planned to use the Arca Swiss only with type 52 Black and White Polaroid Film. The reasoning was that the Polaroid would provide me with prints in the field, bypassing the delay involved in developing and printing a negative image. Instant feedback, and the learning that it brought with it, was what I was after.

My discovery of the Western United States, its vastness, National Parks, the countless attractions it features, and the experience of photographing it with a large format camera for an extended amount of time without a specific schedule, obligations or responsibilities is subject for a book in itself. It is certainly an interesting story to tell, and maybe one day I will write about it, but for now I want to stay with my photographic progress and with the role that my 6 month journey played in it.

In six months I created thousands of photographs. Certainly, working with Type 52 Polaroid was relatively expensive and limited how many photographs I could take. However, I also carried my 35mm, with which I took color transparencies, and I had far fewer limitations on quantity with this other camera.

At the end of the trip, after returning to France, I totaled the photographs that I thought were “up to par” or “interesting enough to show to others.” The numbers were staggeringly low. In 35mm, the format with which I took the largest number of images, I had something like 10 images that I thought were good enough to share with other photographers. In 4x5 format, I had a selection of 100 Polaroid prints that I considered successful. Among those, less than 50 were good enough to be reproduced and less than 30 were images I was comfortable showing to other photographers.

These were ridiculously small numbers compared to what I expected and compared to the duration of my trip. Although I did not have precise numbers in mind when I started, I definitely expected to bring back far more than 40 images that I felt represented what I had seen and experienced during my journey and that I was comfortable showing to other photographers.

My first photograph of the Grand Canyon in 1983 (L) and my all-time best selling photograph in 1999 (R)

16 years of study, practice and knowledge of what customers like and dislike, separate these two photographs. While the photograph taken in 1983 never sold, the image taken in 1999 became my all time bestseller when I sold my work at Grand Canyon National Park. I did try to sell the one from 1983 at Grand Canyon also, but nobody was interested in purchasing it.

Notice how different the foreground element is used in these two images. On the 1983 photograph, the foreground provides very little visual interest but demands of lot of attention because it is the brightest part of the image. It also hides a significant part of the landscape behind it. The colors are mostly unsaturated blues that lack dynamism and excitement. Both over and underexposed areas are present in the image, making details invisible in both shadow and highlight areas.

On the 1999 photograph the foreground follows a dynamic diagonal line, provides a strong color contrast between the green pinion pine trees and the red and blue buttes in the middle ground and background, and offers a wealth of interesting detail for the viewer to study. The colors are dynamic and pleasing to the eye. Finally the light offers soft contrast and warm colors, with no areas either over or underexposed.

7 - What went wrong?

I don't consider myself to be a major talent, so the only solace I can take is to hope I'm growing. - Paul Simon

So what went wrong and why were my results disappointing? Why did my photographs not live up to my expectations? Was I again a victim of the “overrated talent" syndrome?

Only recently did I attempt to analyze this situation objectively. Why? Because for a long time I was more interested in finding ways of creating better photographs than in finding why I was not creating better photographs. Maybe I was guilty of giving too much credit to talent, I really don’t know. All I know is that until recently I never sat down and asked myself why I wasn’t as successful as I expected to be. When I wondered why my photographs were not what I wanted them to be, the answer that presented itself to me, over and over again, was that I had to try harder. Unfortunately, no matter how hard I tried it did not pay out.

Dale Carnegie, as explained by Napoleon Hills in his book “Think and Grow Rich” as well as in his series of books on personal success, gives the best answer I know of as to why I was experiencing frustrating results even though I was working hard: Hard work and long hours will not generate success. You have to have an organized plan. What was missing in my endeavors was not hard work and it wasn’t long hours. It was an organized plan. I did not have any.

Certainly, I had an idea of what I wanted to do. I was able to plan, organize and complete a 6 month journey in a country I had not previously visited. I was able to acquire the necessary photographic equipment and learn how to use it. I was able to create a collection of photographs during the trip, I was able to make a selection of the best images, and I was able to see that these photographs did not match my expectations.

What I did not have in terms of an organized plan was the decision to focus on a specific project. My project, if any, was vague. In short, I wanted to learn how to take better photographs. Certainly, I had narrowed down the equipment I was going to use (4x5 and 35mm) as well as the subject matter (Western US Landscapes). However, that leaves a lot of room to be desired, a lot of blank areas to fill in. And in my case, these blank areas remained blank. I did not have a plan to publish this work in any sort of way for example. I did not know if these photographs were to be enlarged, or exhibited in their original size (4x5). But that did not matter, because I did not have a plan to exhibit these photographs, I did not even have any sort of contact with galleries, nor did I try to establish contact with galleries As a result this work was never exhibited. This did not bother me since it was not a goal.

Besides not having goals for a specific project, I did not have specific goals in regards to learning how to take better photographs. I did not, for example, seek feedback, comments or guidance from anyone. My process was to take a photograph, and evaluate it myself. As a result, my evaluation was only as good as my knowledge level. If I ignored something, and I did, I could not take it into consideration when reviewing my work. Furthermore, this “review” was informal to say the least. It was not written, nor audio, but simply consisted of me looking at my photographs and asking myself if I liked them or not, or if they came close (or not) to the images in Adam’s “The Polaroid Print.”

My direction, also in regards to learning, was also misguided. I used my finances to buy more film, not to buy more knowledge. I remember being in the Ansel Adams’ gallery in Yosemite looking at a signed copy of “The Print”, a book I did not have at the time, and not purchasing it because the cost of the book was roughly equal to that of a box of type 52 Polaroid film. Whether reading “the Print” would have improved my work or not is difficult to answer. However, what I can say is that this decision was representative of my focus at the time which was on taking photographs rather than seeking guidance from external sources.

You may point out that I did have with me one book by Adams, The Polaroid Print, and that when I say I was not seeking outside guidance I am not being totally accurate. This is certainly true, however, it also points to another shortcoming and that is an excessive focus on technique and very little focus on artistic expression.

The Polaroid Print, by Adams, was part of a 4 book series whose three other titles were The Camera, The Negative and The Print. This series was mainly focused on technical aspects of photography, and was aptly named The Technical Series. While it did provide me with guidance, this guidance was primarily, if not purely, technical. There was little coming in from the artistic side. In fact, at that time, I did not consciously consider the artistic side when I photographed. My efforts were mainly directed at creating photographs without technical flaws.

8 - New Directions

Use what talent you possess. The woods would be very silent if no birds sang there except those that sang best. - Henry VanDyke

The question remains as to whether I would have been able to achieve a significantly better image quality during my trip if I had sought guidance from people who were where I wanted to be. I personally think that I would have. The reason why I think this is rooted in one of the comments I made in the previous section: that I could only criticize my photographs in the light of what I already knew. I could not comment on things I did not know about. Certainly, there was a lot I did not know about! Therefore, there were a lot of things I could not comment upon in my work, nor even see for that matter.

In other words, someone more knowledgeable than I was, someone who was where I wanted be in regards to photography, would have been able see things in my work that I could not see myself. They would have been able to point out not only what worked and what did not work, but also what else I could do, what else I could focus on when looking for images. The ability for someone to see something that is eluding you, something to which you are blind, is one of the most important aspects of a critique or review.

What I did do right was not giving up. Even though my results were not at the level of my expectations, I continued to look for ways to improve. And even though I did not come up with the best answers necessarily, I did come up with answers and I did continue to look for additional answers.

9 – Schools

The real issue is not talent as an independent element, but talent in relationship to will, desire, and persistence. Talent without these things vanishes and even modest talent with those characteristics grows. - Milton Glaser

My desire to not giving up is what made me look for ways of learning more about photography. In turn this led me to study photography formally, meaning under the guidance of teachers instead of on my own, using books as guidance.

This was a major move forward, and in a way one can legitimately ask why I did not do so earlier on. After all, I had been studying painting and drawing formally, under the guidance of teachers, by attending the Beaux Arts. So why not do the same right away with photography? Why not start by attending a school of photography, or a series of workshops, or even study one on one with a photographer. My answer, as strange as it may seem, is that photography seemed easy to learn when I first started. Compared to painting, it appeared to be much easier to create a photographic image than to create a painting. I was lured to this belief by the fact that in photography the camera makes the image while in painting and drawing the artist makes the image himself. There is no machine able to perform this role. Therefore, photography must be easier.

However, what I did not take into account was that the making of the image is not the same as the making of an interesting image. While it is true that a photographer does not have to make the image the way a painter does, the photographer has to compose, capture, post process, print, and make countless other creative decisions on the way to creating a fine art print of that image. These steps are no different than those taken by a painter. Only the way the image is created is different.

In a sense I fell prey to the popular belief that when you own a camera you are a photographer. I did not however fall prey to the belief that when you own a paintbrush you are a fine art painter. In fact, this belief is not a reality. People know that owning a paintbrush is just that: owning a tool, an object, an implement intended for the creation of art but unable to create art without being handled by a trained hand. However, when it came to photography, the fact that the camera can create an image regardless of who operates it made me believe that owning a camera automatically made me able to create great images.

American Center and Beaux Arts student cards

It wasn’t so, and the fact remains that up to the time that I started attending photography classes, my paintings and drawings were superior in quality to my photographs. Even though I had failed the Beaux Arts entrance test, I was accepted on the strength of my drawing and painting portfolio. This is testimony to the fact that my work was strong enough to get me in the school. I don’t think I would have been accepted in a photography school comparable to the Beaux Arts, if there had been one, on the strength of my photography portfolio alone.

This fact is testimony to the importance of dedicated study under the guidance of teachers and mentors. In the case of painting and drawing, I was engaged in such study. In the case of photography, I was not. In the light of this knowledge the fact that my paintings and drawings were, in my estimate, superior to my photographs should not come as a surprise.

I started my photography studies at the American Center in Paris. At the time the American Center offered a full-fledged photography program that was headed by Scott McLeay. The program was divided in a series of classes titled “Photography I, II and III”, which covered lighting, exposure, indoor and outdoor photography, darkroom work and more. The program culminated in a group show at the Journees Internationales de la Photographie, the yearly international photography event held in Arles, in Southern France. I did complete the entire program, something that took 3 years, and I did exhibit my work in Arles.

Over the years I studied with a variety of teaches including, in no particular order, Scott McLeay, Al Weber, Joseph Holmes, Charles Cramer, Mac Holbert, Tony Sweet and many more. This learning is far from over, as I continue to study with other photographers. I also now share my knowledge with students, something that I consider to be another learning opportunity.

10 – Conclusion

If you can’t excel with talent, triumph with effort. - Dave Weinbaum

I don’t know for sure if there is something real that we can call talent. Maybe there is, maybe there isn’t. What is sure is that there are people debating for one option or the other, and being very adamant about their beliefs.

For me, if there is such a thing as talent, it is the ability to make the best use of your time, when doing something you deeply care about, by engaging in regular practice, study and dedication. Talent is also seeking help from people who are where you want to be, because the experience of someone who is more experienced than you is one of the most valuable assets you can find. Finally, talent is not giving up when faced with difficulties. Talent, in other words, is the ability to focus, work hard, seek guidance and not give up.

I believe that these are qualities that we all have. I believe that all of us can focus our efforts on regular study and practice. I believe that we can all look for help from those more experienced than we are. Finally I believe that we can all find the courage necessary to not give up in front of difficulty. Therefore, I believe that talent is something we all have. All we need to do is decide to use these abilities, decide to nurture them and allow them to grow rather than leave them unused and ignored.

However, my goal here is not to debate whether talent exists or not. My goal is simply to present my story as an example of the fact that, in my opinion, talent is overrated. Believing that talent alone could do the job, could let me create great artwork, did not work for me. What worked for me was study, practice and focusing on specific projects. Study under the guidance of someone who is where I want to be; Regular practice with a subject that I am passionate about; Specific focus on projects that I care about and that are important for me and that I want to complete.

It took me a long time to find this out. It doesn’t have to take you as long. One of the purposes of this essay is to present you with what I found so that your learning path is shorter than mine. While it is likely that we will all make some mistakes, not all of us have to make all the mistakes. I sincerely hope that the number of mistakes you make will be smaller after reading this essay.

In closing, I want to say this: What matters most is not where we are right now. It is not the skills we have today or the images we are able to create right now. What matters most is what we believe about ourselves. Why? Because it is this belief that will determine what we can become, what we can achieve in the future. It is this belief that will shape the road ahead, it is this belief that will influence which path you are going to take.

When I believed in talent I waited for talent to do the work for me. When I realized that talent is really the ability to set specific goals and deadlines, to focus my efforts in a specific direction, to not give up and to seek help from people that are where I want to be, I stopped waiting and started moving forward. I have not stopped since and the journey I went on has been exhilarating. I certainly hope that you will start your own journey now, if you have not started it yet.

Comments on NPN landscape photography articles? Send them to the editor. NPN members may also log in and leave their comments below.

NPN Contributing Editor, Alain Briot is originally from Paris, France and has made his home in Arizona since 1986. Alain creates fine art photographs, writes books, teaches workshops, and publishes DVD tutorials on composition, printing and marketing photographs. You can find more information about Alain's work, writings and tutorials on his website at http://www.beautiful-landscape.com.

NPN Contributing Editor, Alain Briot is originally from Paris, France and has made his home in Arizona since 1986. Alain creates fine art photographs, writes books, teaches workshops, and publishes DVD tutorials on composition, printing and marketing photographs. You can find more information about Alain's work, writings and tutorials on his website at http://www.beautiful-landscape.com.

You can also subscribe to Alain's Free Monthly Newsletter and receive 40 free essays written by Alain when you subscribe.