|

|

Flash Primer 2 Photography and Text Copyright Joe McDonald

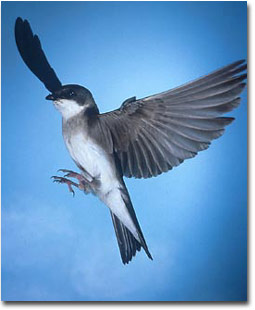

In the absence of natural light using flash is easy, but when ambient light is present the use of flash can be problematic. If there is ambient light, you cannot ignore it, and now your choice of shutter speeds is very important. Normally, when there is ambient light we usually expose for it, selecting a shutter speed and aperture that yields a correct exposure. But if you are going to use flash, you don’t necessarily have to expose for the ambient or natural light. You can, if you wish, select a shutter speed/aperture combination to completely underexpose the ambient light, where the flash provides the sole light source for the exposure. Theoretically, if the correct ambient light exposure was 1/125th at f16, using 1/1,000th at f32 would underexpose the ambient light by 5 f-stops, while the flash properly exposed the subject. Unfortunately, you can’t just arbitrarily select any ol’ shutter speed you wish if you’re using a flash. That’s because the shutter must be fully open when the flash fires. This is the camera’s synchronization speed or ‘synch speed,’ which in most cameras is 1/250th sec or less. So you can’t just switch to 1/1,000th sec. and fire and expect the flash to do its job. It can’t. In fact, if you try, two things may happen, depending upon your camera system. The camera may recognize that a flash is mounted and automatically switch to the fastest flash synch speed (let’s say that is 1/250th), which would only underexpose the background by 3 stops (remember, we started at 1/125th sec. at f16 and attempted to shoot at 1/1,000th sec. at f32). Alternatively, the camera may fire at the selected shutter speed (1/1,000th sec.) but the flash will be out of synch and none, or only a small portion of the film will be exposed. There have been some advances here technologically, and some camera and flash systems offer a high speed flash synchronization where you can use shutter speeds higher than the normal synch speed, but the power of the flash is reduced progressively as you increase each shutter speed. Consequently, your working distance will decrease, and although you might be able to use that desired 1/1,000th sec. shutter speed, you won’t be able to use f32 unless the flash is very, very close to the subject. There is an exception with some digital cameras. Some digital cameras have a flash synch speed that goes up to 1/1,600th or 1/2,000th sec.. I couldn’t believe this until I tested this out for myself on our recent hummingbird shoot. If you shoot digital, check this out with your system. You’ll know immediately if the camera is synching at fast speeds or if is not. If it is, you’ll have a flash-generated image that fills the entire LCD screen. If it does not, the image will either be black or only a portion of the screen will be illuminated. In teaching, both at our Complete Nature Photo Course and our Advanced Course that deals specifically with flash, I encounter many misconceptions concerning flash photography. Although most participants have used flash to one degree or another, most have little understanding about how an ambient light exposure and a flash exposure can work together to create the desired effect. For example, one could make an image where the subject is correctly exposed by flash and where the ambient light background is underexposed by one stop, two stops, or by three, four, or more. Alternatively, one could underexpose the subject by x number of stops and silhouette that subject against a background that is illuminated by flash. That’s not too commonly done, but it is possible and would be useful if you’re making a silhouette. Should you choose to underexpose the ambient light you can do so by either changing the shutter speed or the aperture, or both, but when flash is involved you must remember your flash’s synch speed as well. If your system has a high speed flash synch there’s fewer limitations, but remember that the power of the flash decreases, and small apertures will required short flash-to-subject working distances. In my last column I briefly mentioned photographing tree swallows flying to a nest box and shooting these birds with natural light and with flash. On a ‘Sunny 16’ type day, I could shoot a natural light exposure with a shutter speed as fast as 1/2,000th sec. with an aperture of f4 with ISO 100 film. That is, of course, a reciprocal exposure to 1/125th sec. at f16, just as 1/500th sec. at f8 is a reciprocal. I might, and let me stress, might be able to stop almost all of the bird’s movement at a shutter speed of 1/2,000th sec., but my depth of field would be almost nothing at f4.

When using flash, remember, I’m limited to a shutter speed of 1/250th sec. or less. Under sunny conditions that slow a shutter speed cannot stop a swallow in flight. A flash could, but just because we’re using a flash does not mean we can simply ignore the effect ambient light will have on the image. To help to understand this, just for a moment let’s consider what advantages using a flash would provide if ambient light was not a factor. The brief burst of light of a flash, a duration that can be as long as 1/1,000th sec. or as short as 1/50,000th sec. would stop the bird’s motion, and certainly would do so at the faster flash pulses. If the flash were close enough, or powerful enough, there might also be sufficient light to use a small f-stop, providing for great depth of field in the image. Now, let’s consider this situation as it really exists, and that’s with ambient light present since our tree swallows fly during the day. In bright ambient light with a moving subject and a flash synch speed of 1/250th sec. I’ll probably have a problem, and that’s a phenomenon called ‘ghosting.’ ‘Ghosting’ is a double-exposure recorded virtually simultaneously. The flash records one exposure – usually the sharper of the two since the flash duration is so brief, and the ambient light records the other exposure. The ambient light exposure is often faint or blurred, especially if the subject is moving faster than the shutter speed can freeze the action. How could I stop the tree swallows and not get ghosting? Shoot them at night, using flash! Just joking – that’d be the easy solution but swallows do not fly at night. Using flash to freeze the flying swallows and yet avoid ghosting, I had to do some thinking. Here’s the solution.

I just said, when you’re using flash in bright ambient conditions your film is exposed to two light sources – the natural light and the light of the flash. There’s no way of getting around this, IF the ambient light is going to register on film. However, it doesn’t have to. By purposefully underexposing the ambient light you can, in effect, ‘erase’ all natural light so that it does not register on film. Normally, to underexpose film all one need do is to increase the shutter speed and decrease the aperture, but remember, there’s that awful flash synch speed you have to contend with. So what do you do? There’s a couple of ways to reach the solution. Let’s consider the worse case scenario: you’re photographing our tree swallows on a sunny day. Under those conditions, with ISO 100 film the base exposure can be no brighter than 1/125th sec. at f16 (classic Sunny 16 conditions). If your camera synchs at 1/250th, and if you can close down your aperture to f32, you’ll underexpose the ambient light by 3 stops. If your flash synch doesn’t go to 1/250th, or your lens doesn’t go down to f32, then your underexposure will, of course, be less. Three stops of light should be enough to effectively erase the natural light, but to be sure you might wish to go further – to four or five stops. There are several ways to do so. You could switch to a slower ISO film. At ISO 50, the same settings (1/250th sec. at f32) now yield a 4 stop underexposure. If you added a 1.4X tele-converter, you’d lose another stop for a total of 5. Of course, you could use neutral density filters, a 2X tele-converter, or a polarizing filter to achieve the desired amount of underexposure. I gave Sunny 16 conditions as the worse case scenario because that’s the brightest lighting you’ll have. If it’s overcast or dreary and the light levels are already low simply using 1/250th sec. at f32 may underexpose the ambient light by 5 or 6 stops. Once you achieve the required underexposure your flash will do all the work, and you’ll base your exposure solely upon the light provided by the flash. However, you’re not done yet. If you illuminate ONLY the tree swallow, the resulting image will indeed look as if the birds were flying at night, and you don’t want that. When you underexposed the ambient light you did so for the entire image, both on the bird and on the background. This would not be so if the background was a bright sky which is usually much brighter. But don’t even think of using the sky as the background! That would surely cause ghosting as the film would once again register light from two light sources, and the 1/250th sec. shutter speed would be too slow to stop the flying bird. You’d end up with a blurred swallow silhouetted against the sky.

The easiest way to produce an exposure that looks natural, in that both the subject (the tree swallow) and the background are exposed is to illuminate both with electronic flash. It doesn’t matter whether the background is natural or a prop (posterboard, picture, whatever). What is important is that the flash that lights the background is firing at the same flash duration as the one that is hitting the subject. If one is firing at a slower flash duration there is a good chance of recording ghosting. One flash, theoretically, could illuminate both the subject and the background, but this would introduce the likelihood of a shadow cast from the subject falling upon that background. It’s actually easier to illuminate each separately. In fact, I’d go further and advise illuminating the subject with two or more flashes to reduce the possibility of contrasty lighting as well. One flash may illuminate one portion of the swallow while casting another part of the swallow in deep shadow. Two flashes will provide more even lighting, effecting canceling out each other’s shadow. For our shooting I often use three flashes on the subject – two in front, and one positioned a bit closer behind the back to provide a rim or ‘hair light’, that really sets the subject off from the background to produce a more authentic 3-D look. Continuing with our example of a tree swallow in bright sunlight, recall that we needed an exposure of f32 to underexpose our ambient light by 3 or more stops when using a shutter speed of 1/250th sec. An aperture of f32 could be achieved with a TTL flash, but this would require placing the flashes fairly close to the subject. Recall that using a tele-flash extender will concentrate a flash’s output into a smaller area, so the flashes could be placed further back – at least doubling the distance in most cases. In my last column I promised to get you going on photographing tree swallows or other subjects in daylight. Putting to use what you’ve just learned, that is, underexposing the ambient light by 3 or more stops and illuminating the subject and the background with flash will get you started. If you review that column, however, you’ll note that using small apertures like f32 generally results in long flash durations, and these may be too slow to really stop a tree swallow in flight. Again, with a tele-flash extender, the flash duration will be shortened, but it may not be enough to really stop a flying bird dead in its tracks. In our next column, we’ll take another big step. You now know TTL flash, you understand the relationship between ambient light and flash, and you are primed for what I consider to be the key to action-stopping flash photography. That’s using a flash on manual mode where you control the flash duration. Get ready for the exciting world of high speed flash photography! Joe and Mary Ann - NPN 020 Comments on NPN flash photography articles? Send them to the editor.

Joe has been a full-time nature photographer since 1983, and Mary since 1989. They have led photo safaris to all seven continents, and spend as much as 20 weeks per year in Africa. Their work has appeared in every major natural history publication in North America. Joe is an active member of the Outdoor Writer’s Association of America and a former board member of the North American Nature Photography Association. Mary is a first place winner in the BBC/BG and Nature’s Best photo competitions. Joe and Mary maintain an active website that offers many features, including tips and questions of the month, a viewer’s gallery, product reviews and links, and trip reports and portfolios. Complete photo and digital course and photo tour descriptions are available on their website, www.hoothollow.com. |

|

|

Joe and Mary Ann McDonald conduct photo and digital workshops at their home in Hoot Hollow, Pa., and lead photo tours and safaris around the world. Joe is the author of 6 books on wildlife photography and 1 on African wildlife; Mary is the author of 29 children’s books on natural history. Joe is a columnist for Outdoor Photographer Magazine, and Joe and Mary are columnists for photosafaris.com and Keystone Outdoors, and field correspondents for Nature’s Best Magazine.

Joe and Mary Ann McDonald conduct photo and digital workshops at their home in Hoot Hollow, Pa., and lead photo tours and safaris around the world. Joe is the author of 6 books on wildlife photography and 1 on African wildlife; Mary is the author of 29 children’s books on natural history. Joe is a columnist for Outdoor Photographer Magazine, and Joe and Mary are columnists for photosafaris.com and Keystone Outdoors, and field correspondents for Nature’s Best Magazine.