The Road Not Taken: The Power of Wilderness Photography |

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

— Robert Frost, “The Road Not Taken”

"The Road Not Taken"

I don’t much like shooting icons. They always seem too crowded—and not just with other shooters, standing shoulder-to-shoulder by the dozen, forming an ensnaring web of tripod legs. There’s also the ever-growing procession of photographers that have come before, a parade of ghosts that haunt places like Delicate Arch and Half Dome. Their voices chant like a chorus, urging your hands to frame the tried-and-true compositions of sunrises and sunsets past.

But places still remain, in the wilderness, where the outer voices are silent, and the inner voice can be heard above the din. Wilderness photography has its perils, but it also holds a singular power: a chance to make fundamental images, the likes of which have never been seen before.

"Fitz Roy"

One of the most compelling artistic statements I have ever seen is Craig Blacklock’s book “The Lake Superior Images.” Blacklock spent years exploring and photographing Lake Superior by sea kayak, culminating in a three-month circumnavigation of the lake. His haunting images are more than a mere collection of trophy shots—they weave a primal story of ancient waters. His was a journey within as much as it was without. By venturing into the proverbial wild, a photographer can find not only the essence of a natural place, but also—not unlike the mythic heroes and prophets of old—his or her true soul.

Sometimes, the soul-searching wild can only be found through an epic journey, like Blacklock’s. Sometimes, it can be found just a few feet into the forest (the truth is, many photographers never stray far from asphalt). Wild places aren’t necessarily miles away from nowhere, but they are off the beaten path, away from the passages that others heavily tread. Often, they are found in the wilderness within, arising from a willingness to push past mental, physical, and artistic barriers in an effort to find a unique perspective.

Although my recent backcountry trip to Patagonia failed to live up to the “epic journey” standard set by Blacklock, I nonetheless got a chance to experience wilderness in a way that is often hard to come by in the crowded national parks of home. Patagonia contains some of the most stunning and rugged mountain wilderness on Earth, complete with sky-piercing mountains, hanging glaciers, and clear mountain lakes that glimmer like sapphires. I spent two weeks trekking through the unforgiving Patagonian backcountry—climbing glaciers, crossing swollen rivers via Tyrolean traverse, and enduring lung-busting ascents and gale force winds—looking for places and moments that could reveal the essential character of this magnificent land.

"Heaven and Earth"

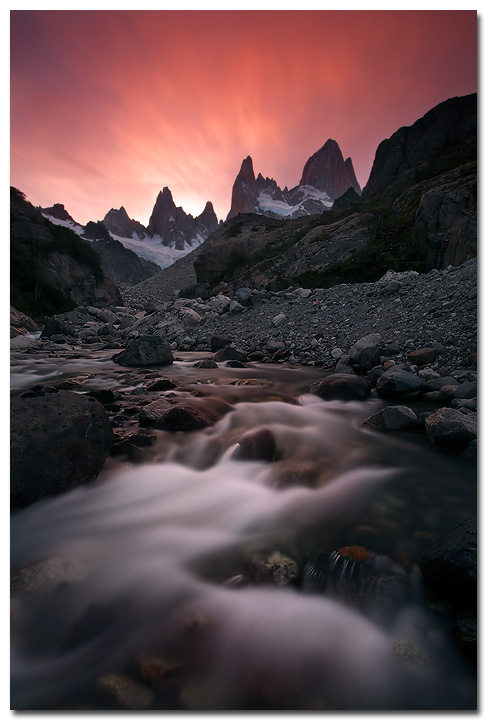

The whole time I was in Patagonia, I searched for a particular photograph—an image that existed first only in my mind, waiting for me to pluck it from the living world. I envisioned a clear mountain stream flowing forth from a mountain paradise, and I spent two weeks climbing high and low to find it. More often than not, whenever I engage in this type of “pre-visualization” exercise, it proves to be fruitless, as imagination tends to construct mythical scenes that fail to be matched by reality. This time, however, I got lucky, and I found my chimerical stream deep in the Patagonian wilderness.

"Journey's End"

Wilderness photography is challenging and demanding, and second chances are scarce. After a grueling two-day ascent over unrelentingly steep scree and a sloping glacier, one morning I stood atop remote Paso del Cuadrado, overlooking one of the most incredible views on Earth. Fitz Roy, Torre, Pollone, and Gran Gendarme—peaks of legend—stood arrayed before me, mighty spears piecing the heavens, kindled with fire from Aurora’s light. One place, one moment—and only one chance to get it right.

“Cerro Gran Gendarme”

One of my favorite images from the trip is of a lonely boulder perched in the middle of nowhere. I trekked for several days to reach this remote spot, crossing over the crest of the Andes Mountains and descending to the other side, not seeing another soul (other than my guide) for three days. The scenery was not as “stand-up pretty” as in the more popular front country, but it was moving nonetheless, somehow more stark and otherworldly than anything I had ever encountered before. I found the boulder perched atop striated rock, a remnant from glaciers of old, while exploring alpine meadows far off trail. I experimented with long exposures at sunset to enhance the preternatural mood of the scene, letting light and time paint across the image frame for several minutes, and reflected on the fact that I had traveled to the far side of the world to photograph this forlorn rock. I was probably the only person who ever has, and likely the only one who ever will.

"The Far Side of the World”

All paths to the wild are fraught with danger, so be cautious. Before venturing forth, make sure you have the necessary skills, health and fitness to overcome the challenges you might face. If traveling alone, let someone know where you plan to go. Consider carrying a GPS locator or satellite phone in case of emergencies. Above all, bring a positive mental attitude. You may have to endure bad weather, biting insects, mud and filth, exhaustion, and loneliness, so finding ways to keep morale high can make all the difference.

Beyond that, I have only one last bit of advice: travel light. Wilderness is rugged and demanding, sapping precious reserves of energy. Too much gear will bog you down. Stay nimble, and let the call of wild places be your Muse.

To see more images and read more about my Patagonia adventures, please visit my Patagonia Photo Journal.

Comments on NPN nature photography articles? Send them to the editor. NPN members may also log in and leave their comments below.

NPN Contributing Editor Ian Plant is a full-time professional nature photographer, writer, and instructor. His images and instructional articles have appeared in a number of magazines including Outdoor Photographer, Popular Photography, National Parks, Blue Ridge Country, Adirondack Life, Wonderful West Virginia, and Chesapeake Life, among others. Ian also writes a regular blog column for Outdoor Photographer Magazine Online. Ian is the author/photographer of eight print books. His most recent book, Chasing the Light: Essential Tips for Taking Great Landscape Photos is a 62-page downloadable PDF eBook. To see more of Ian’s work, visit Ian Plant Photography.

NPN Contributing Editor Ian Plant is a full-time professional nature photographer, writer, and instructor. His images and instructional articles have appeared in a number of magazines including Outdoor Photographer, Popular Photography, National Parks, Blue Ridge Country, Adirondack Life, Wonderful West Virginia, and Chesapeake Life, among others. Ian also writes a regular blog column for Outdoor Photographer Magazine Online. Ian is the author/photographer of eight print books. His most recent book, Chasing the Light: Essential Tips for Taking Great Landscape Photos is a 62-page downloadable PDF eBook. To see more of Ian’s work, visit Ian Plant Photography.