|

|

Fear of Photoshop

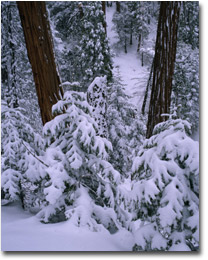

Text and Photography Copyright Michael Gordon I manipulate my images, and I am not afraid to say it. I am proud of my exhibition/gallery prints. Every one of them has had various levels of manipulation, from very little to quite a bit, but every last one of them has been manipulated. Let’s define the word: in this article, manipulation refers to cropping, color balancing, contrast adjustments, and burning and dodging. Compositing (‘negative sandwiching’ or blending exposures digitally) and ‘photo art’ (using Photoshop filters and artistic brushes to render the appearance of a painting or something other than a photograph) are not topics addressed within this article. In addition, this article does not deal with photojournalism, documentary work, or the work of those who must provide transparencies that match online images (stock and editorial work). In a nutshell, only straight expressive fine art photography (the majority of photography seen on NPN) is the topic. I can already feel some readers squirming; those who are uncomfortable accepting post-exposure cropping and dodging/burning as within the confines of straight photography; those who post their images on NPN or elsewhere with the bold note “no digital manipulation” as a badge of honor. Well, here’s the scoop: darkroom manipulation is nothing new. Traditional darkroom printmakers have developed, practiced, and perfected these techniques for the better part of a century. Those who insist they are against manipulation of photographs have viewed and probably commented quite favorably on possibly hundreds of such photographs, as nearly every good, practiced printmaker is manipulating their prints. Only now is digital manipulation being called into question and held up to scrutiny because of the ease with which a photograph can be made ‘unbelievable’. It is not just photographers that are now aware of or concerned about untruths in photography. Anyone with a modicum of computer talent and a basic image-editing program can see how easy it is to ‘fake’ a photograph. It’s no wonder why everyone is so squirmy about the idea of photographic manipulation, even when it’s been occurring underneath the eyes of everyone for a century. Dyed-in-the-wool wet darkroom traditionalists are extremely resistant to digital technology and the use of Photoshop because they often feel that digital is ‘cheating’, somehow completely unlike their darkroom manipulations (see the websites of Michael Fatali or Christopher Burkett). Newer photographers believe that any alteration of an image is somehow ‘wrong’, not yet aware that as their level of commitment to the craft of photography and printmaking increases, they too will begin to manipulate their images either in the wet or digital darkroom. Ansel Adams was perhaps the first well-known photographer to heavily manipulate his images. Have you ever seen a straight print of Ansel’s Moonrise Over Hernandez? You might be shocked when you do. Adams’ now famous statement “the negative is comparable to the composer’s score and the print to its performance“ could very well be considered the mantra for most modern photographers. I will go so far as to suggest that a straight print – one with no manipulations whatsoever – often isn’t worth a second look (there are exceptions, of course). In order to coax light from the film and convey in a print what most photographers saw and felt at the time of exposure, varying degrees of manipulation are often needed to convey the expression of the artist and the mood of the scene. Amongst the Photoshop-fearful there exists a misconception that any technically incompetent and artistically challenged photograph can still be made to magically come to life through digital cheating. Without a good composition in good light, no amount of digital wizardry or Photoshop plug-in’s can coax a pulse into a photograph otherwise devoid of life. A good photograph and a good print are not synonymous, yet both require each other to effectively and beautifully execute the vision of the photographer. Why does a photograph need post-exposure manipulation? Danny Burk’s Teton Sunrise Series illustrates perfectly just how inadequate film is at rendering what our eyes can see. Black and white film can generally produce detail through a range of about eight stops (Zone II through Zone IX), while transparency films can only capture about half that. In ordinary situations, most people can see with their eyes detail in deep shadow and detail in bright (not specular) highlights – both at the same time. Imagine yourself in a gloomy cathedral, for example; no film can cover the range of tones in that cathedral without blocking up some shadows or blowing out the highlights streaming in through the stained glass. Observe in Burk’s series that as the sun rises, the trees fall into ever deepening shadow, rendering almost no detail in the fourth and last of the series. Burk - probably no different than most other humans with functioning eyes - was able to see into the details of those distant trees, even though his film failed to record those details. Our brains and eyes also make color corrections in scenery where our film again fails us. When photographing in deep shadow, if we fail to employ an 81 series filter, our exposures will have a cool blue cast even though our eyes may not have observed that blue cast in the scene. We might have even used an 81C warming filter, but it still might not have been enough warming for the scene. And what of scanning issues? During the film scanning process, we must often hold back midtones or three-quarter tones so we don’t blow the highlights (see my photograph at the end of this article). Conversely, we might have a scene that is so dark we have to open it up to a degree that sacrifices tonality in quarter-tones or highlights. Such scanning issues call for controlled and often judicious digital contrast masking to express the scene the way we remembered it (not the way our film recorded it). In these scenarios, posting an unmanipulated scan on the web or off to the printer is a sure-fire method for rejection and disappointment. And what about cropping? Cropping itself used to be considered an art. Most of those who assert they do all their cropping in-camera and would never post-exposure crop often belong to the same group that fears Photoshop and any form of post-exposure manipulation. Have you ever used a telephoto to extract elements and compress the scale of a scene? Have you ever used a polarizing filter to minimize glare or saturate colors? Have you ever used a red filter to darken skies or a green filter to lighten foliage in black and white photography? These are all examples of photographic manipulation. Expressive photography is always an interpretation of reality (the artist’s interpretation). To put it another way, photography is never a literal interpretation of reality. Post-exposure manipulation – in digital or traditional forms – are simply tools that we can use to make expressive prints that transcend the limitations of film yet fulfill our vision and imagination. Eschewing such tools is nothing short of limiting your photographic potential. I conclude this article with my photograph Incense Cedars and White Fir, New Snow. The point of and detail in these photographs is better illustrated if viewed on a calibrated display. If not, CRT viewing is highly recommended. Click on the thumbnails for links to larger versions.

Lest I be accused of scanning trickery to prove the point of this article, Figure A is a straight (no manipulation whatsoever) 200mb Tango drum scan performed by Jeff Grandy at West Coast Imaging in Oakhurst, California. Note the overall darkness of the image (intentional to preserve highlight detail in the snow) and the tremendous blue cast from shooting in overcast and snowy conditions. Figure B is the very same image, but I have performed basic color correction and levels adjustment to make it a more pleasing image to look at. It certainly looks better, but is still lacking the visual punch and vibrancy to make it an exciting print. Figure C is my completed master file that I make my prints from. This master file is about 500mb, has nine layers (Photoshop) and was the result of a number of hours of work (that still continues nearly each time I print it). It is unimportant that I document here what action every layer performs. What is most important is that I have succeeded in making the image and print match my interpretation of the scene and express my vision. Have I fundamentally changed the photograph? Have I distorted reality? Have I made a much more pleasing image to study? Before you write off digital manipulation, have a go at it with one of your photographs and determine for yourself whether Photoshop is digital trickery or just another tool to help express your creative vision. Michael Gordon - NPN 492 What do you think? Visit NPN's Interactive Article Forum and join our discussion on this article! |

|

|