|

|

||||

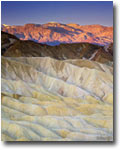

So what has this got to do with photography you ask? Well a lot actually. To understand any creative endeavor one must first understand the roots of the artist’s creative urge – the reason he or she would pick up a camera or a pen or a canvas with the intent of making something they can share with humanity at large. For nature photographers that reason is usually a personal relationship with, and perception of, the natural world. For some it is a collection of beautiful elements – shapes, colors, patterns, and textures. For others it is a spiritual meaning, a refuge, a political objective, a religious calling, or any number of other reasons that culminate in one thing - we care about it. We care about it with a passion that demands expression. In the case of Doug Peacock a passion fueled by frustration resulted in some scathing articles and acts of rebellion, but also prompted him to produce some profound nature writing and sensitive wildlife footage that are as pure and beautiful and innocent as you will find anywhere. In my own case a turbulent history and yearning for the wild had led me to seek and capture raw beauty, whether in intimate detail or grand majestic vistas. An ever-present tension among nature photographers (and photographers in general, especially in this day and age) is the ongoing debate of “manipulation” along with criticism from those who believe that many nature images are idealized views rather than representations of “reality.” Indulge me if you will for the next few paragraphs as I try to articulate my own thoughts on the value of “pretty pictures” and renditions that go beyond merely documenting a scene and into the realm of personal expression. My initial forays into the natural world as a child involved roaming in fields that at the time seemed endless. Coming home from school I would eat a hurried meal, do my homework and run outside. My world involved shrubs and trees and insects and birds and caterpillars and snakes and tortoises and snails and small mammals, and I wanted to know and see and touch and learn everything I possibly could. I would peek into nests, attempt to feed, pet, and talk to just about any living critter. I was fascinated by everything around me and literally spent hours and days walking farther and deeper into the fields and orchards. It never occurred to me that there was a war going on, that money was scarce, that family members were ailing, that people were working and struggling, that the world was changing. The fields were always there and as a child I took it all for granted. Growing up, I kept watching as the fields disappeared, as the things I used to know became pale shades of their former selves, as once-abundant species vanished, as ugly construction took over. I wanted to protest, but how? Later in life I was introduced to the writings of Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, Aldo Leopold, Wallace Stegner, Ed Abbey, Jack Turner, Doug Peacock, and many more angry men than I can list; angry and rough and outspoken and rude and infinitely sensitive men who could relate to the beauty of the natural world with the same sacred and naïve fascination as I had in my childhood. Abbey could call for acts of sabotage while at the same time describe a desert flower with such delicate detail and emotion that you could almost touch it. Thoreau could fault everything about the industrial world while rambling about a simple walk in the woods with such passion that you could almost smell the damp forest air. Turner could hurl fire and brimstone at everyone responsible for the loss of wildness in our society, alongside gentle descriptions of the moods of mountains and the songs of pelicans. In these writings I saw myself and I knew I needed an outlet for my anger, not through fighting or politics or preaching, but through creative expression. So, when I show you a beautiful landscape, don’t ask me if this is how it “really” was. I will answer yes every time – this is how it really was, and is, to me. This is how I want to see it and share it. Yet, as an artist I also seek to create something unique and personal. I can see the seeds of beauty, the potential for greatness, and sometimes the reflection of former glory even in the most mundane of natural scenes, and I consider it my duty to share them with the world. Yes, the common perception known as “reality” may be different from my personal rendition, but it is always in the spirit of the place and the scene and the emotion it inspired in me. If all I can show you is what you can see or create by yourself then what standing do I have as an artist? I want to teach and educate and arouse and inspire and prod my viewers. I want them to react with pleasurable surprise and demand to know more, demand to preserve the beauty, maybe ask why it is no longer as I have shown it to them and what they can do to help. I want to make them as angry as I am at those who would give up on such beauty and allow it to go unseen and unpreserved. So please, let’s not dwell on the minutia of “manipulation.” What I place in front of you is how I interpret the scene; it’s how I want to communicate it to you and it is true to the spirit of the place. All our views of the world are manipulated and filtered through a plethora of ideas, beliefs, preconceptions, and flawed senses. Bear with me and I’ll show you something truly special that you may never see had I not shown it to you. If I can’t, then I am no artist. GT-NPN 0440 Comments on NPN landscape photography articles? Send them to the editor. Guy Tal resides in Utah, where most of the Colorado Plateau's breathtaking grandeur can be found, and where issues of preservation and land-use are among the most prominent on the political agenda. Guy's large format photography can be viewed on his website at http://scenicwild.com. | |||||

|

|

|||||