Selling Your Stock PhotographyText and photography copyright Charlie Borland. All rights reserved.

Return to Nature Photography 101 Index

Editor’s note – With the ever-growing interest of photo buyers in the work displayed on PhotoPortfolios.net, I asked full time stock photography professional Charlie Borland if he could give some advice to members on how to handle inquiries from those who are interested in purchasing rights to use their photos. Our sincere thanks to Charlie for sharing his expertise with us in this article!

You have just been contacted by a prospective client who wants to buy one of your images for a specific use. If you are new to selling your photography your first thought may be “now what do I do”? As landscape and nature photographers, we hope to sell our images and generate some income. This helps offset equipment costs, allow further adventure, or pay the household bills. Whatever your financial need, the skill of negotiating licensing fees for usage of your images can be intimidating as we never want to lose a sale. But, with a step by step approach simplifying the process, you can easily determine a fair and justified fee.

This calendar, published years ago, paid a set price of $100 plus $50 for the cover. This publisher now pays $150 plus $100 for the cover. The prices are set and non-negotiable.

|

|

There are basically two ways prices are determined. The first is when the client asks what your price is and the second is when they inform you of their established prices. If you choose to submit your images to calendar companies, gift card companies, book publishers, and many other publishing markets with established rates, you are in essence agreeing to their pay structure simply by submitting. When a client contacts you regarding usage of your image they may ask your price or inform you of the price they are willing to pay. You then have the option of agreeing, disagreeing, or attempting to negotiate a price that is more favorable to you since rarely are you offered too much money.

You may also be contacted by an advertising agency, graphic design firm, or a company who has heard of you, seen your photographs published somewhere, or looked at your online portfolio or personal website. If there is an image that they are interested in they will inquire as to your prices for a specific usage they have in mind. From here forward your ability to negotiate favorable prices for your work will in the long run provide you a better return on investment for your stock photo business.

The Market Today

To determine a usage fee you need to look at what you shoot and how your images fit into the market since today’s prices for stock are in reality all over the place. How much money can you make? The sky really is the limit and it depends on your photographic product and ability to sell them. In the 1990’s the average stock photo sale was around $325 with many sales higher and many lower. Today the average is less than $200 and often closer to $100. If you were with a large agency back then, you could use a rough estimate of earning $1 per month for each image in an agency file. Now it is closer to 10-20 cents per month, per image, and current data may no longer support this. Keep this in mind when deciding the best way to market your imagery as making good money from your stock photography boils down to the art of negotiation!

What do you shoot?

This is the first important factor in determining the value of your work. You must clearly know where you fit into the market and who your competition is. Do you specialize in the national parks, the natural areas around your home, wildlife, flowers, or adventure? Is the work you create similar to all the other photographers in your area? If you photograph the national park system, are you going to all the same places you have seen published? Are your wildlife images from the zoo or a game farm?

If you have a niche specialty, then the value of your work would be higher. An underwater photographer who specializes in sharks can demand far higher prices than the flower photographer. This can be calculated simply by looking at the supply of these two subjects and demand for both. These are important points. If clients are interested in an image you have, but can also get the same or comparable image from someone else, then a bidding war could start and the price will be forced lower.

Is your work more suitable for Royalty Free or Rights Controlled pricing?

Once upon a time all stock photos were rights controlled (RC) and the price for a photos usage was negotiated on how it was to be used; how big it was going to be used, and how long it was going to be used. Then PhotoDisc was founded and Royalty Free (RF) stock photography was formed and the world has never been the same. You can choose to shoot for one or the other and it is imperative that you understand the difference.

These two images represent a Royalty Free type image and Rights Controlled. I don’t personally sell Royalty Free images, those are for sale on the web. I would rather negotiate a license that gives the client the uses they want for a reasonable price. The US Capitol in Washington DC can be found all over stock photo websites. This image has sold well, but I must price it lower to make a sale or clients will go to the web. The forest photo from Redwoods National Park is an image created by being at the right place at the right time. It has generated total sales of around $12,000 with the lowest priced at around $250 and the highest of $3000. It is a one-of-a-kind image and when it fits a client’s concept, they are often willing to pay more.

These two images represent a Royalty Free type image and Rights Controlled. I don’t personally sell Royalty Free images, those are for sale on the web. I would rather negotiate a license that gives the client the uses they want for a reasonable price. The US Capitol in Washington DC can be found all over stock photo websites. This image has sold well, but I must price it lower to make a sale or clients will go to the web. The forest photo from Redwoods National Park is an image created by being at the right place at the right time. It has generated total sales of around $12,000 with the lowest priced at around $250 and the highest of $3000. It is a one-of-a-kind image and when it fits a client’s concept, they are often willing to pay more.

|

Today, RC and RF images are defined by many factors including how difficult the image was to obtain. RC images command two to three times the usage fees as RF and often more than that. RC images might include an image that was difficult to get; for example, lightning across the Grand Canyon is very difficult to obtain. However, an image of the Grand Canyon taken on an average day, with no special situation is a dime-a-dozen and would do better as an RF image. RC images are still licensed by the usage and if the client wants to use it again, beyond the original negotiated terms, they pay again. Clients pay for RF images once and can use them without any additional compensation going to the photographer.

There is currently tremendous pressure on photographers to lower prices and be more competitive with website prices and royalty free. I resist this pressure to the point of losing some sales. If a human (me) has to be involved in a stock sale the price is higher than if they download it off the web. A transaction involving my time and effort costs more to complete than an automated web transaction.

I have an acquaintance that’s a well known travel photographer and has made a living off images of the Tokyo skyline, Big Ben in London, the Eiffel Tower, Golden Gate Bridge, and many of the world’s great tourist spots. All these images are available for download off the web for a fraction of what he was able to earn from each image. This point emphasizes your need to determine what type of imagery you shoot and where it fits into today’s markets. Are you shooting Royalty Free or Rights Controlled imagery? Your pricing should be influenced by your answer.

Local Buyers vs National Buyers

There is a difference to some degree in whether the potential buyer of your work is local or national and how you can negotiate with them. A local buyer may be calling you for some spectacular shot of yours they have seen, but may also be calling you to make a photo request on generic local subjects. They may also be contacting other local photographers they know and making the same request. I always inquire as to whether they are contacting other photographers or do I have the sole pleasure of filling their photo needs. If they are in talks with other photographers for the same images then the pricing will be more competitive than if I am the only person whose work they are looking at.

If the potential buyer comes from a different region of the country and is looking for generic local images, I again inquire as to whether we can be their sole source of images and possibly mention a quantity discount should they work exclusively with us. The buyer will most likely know of fewer photographers to contact since they are out of the area and this helps me. This same buyer may also be calling more for a specific image they have seen in the many places I have advertised my stock imagery. In this case, they could be set on a specific image and it boils down to getting the price.

It is very common for a designer to use a low resolution image off the web or cut from a stock catalog and to paste it into a “comp”. This composite layout is often designed to illustrate their idea for an advertisement or brochure and then presented to their customer for approval. If the customer buys off on the idea, then the designer will be calling you to inform you that they “are considering” one of your images for a project. Often I had no idea that my image was being considered so when I receive such a call and the client says they would like to use my image in a specific project, I inquire as to how it will be used and whether they have a comp I can see. If they provide me a fax copy of the comp, this indicates to me that the customer has probably seen how my image will be used and bought off on the idea. In this case your negotiating position has just increased dramatically because the designer’s customer has approved of the layout and is expecting to have that photograph appear in their project. Now it is time to negotiate a price.

One other point regarding buyers: Are they veterans to buying stock imagery or new to it? Are they with an advertising agency or represent the PR department of a local development company for example? The person from the ad agency will have experience dealing with the negotiations for stock photography and savvy to how the pricing works. This means that you may have a harder time getting everything that you want while this client will also a have a good understanding of what the price should be. The person from the PR department who may never have negotiated for stock may be shocked at your price but also more willing to go along with a reasonable price and the rights you want. Understanding who your client is will aid you in being on target with your price and negotiating position.

Evaluating the Usage and your Image

Here is the same photo in two uses, one for a non- profit private school and the other for a shopping center. The private school piece is a brochure, limited visibility, non-profit, and 15K print run. Licenses fee $400. The advertisement is for a shopping center with a time limit to run in local magazines of 3 months. License fee $825.00

|

|

So the client really likes your shot from Canyonlands National Park. It is an incredible shot, right before sunset and the puffy clouds are bathed in golden light. There is room for copy and the catchy marketing title they plan to use in their promotion selling water filters. They want a price, so where do you start? I look at numerous factors that must be determined in order to come to my proposed license fee and I start with what I call the primary considerations:

- How is the client going to use it?

- What size is the client using it in their publication?

- What is the print run or length of time a client wants to use the image for?

- What rights does the client request.

Once I have these factors I can look at several photo pricing resources and come up with my initial usage fees. There are however, some important secondary considerations that must also be taken into account:

- How unique is the image?

- Is it a one-of-a-kind or a dime-a-dozen image?

- Is there production value?

I have designed a worksheet with these primary and secondary considerations that need to be answered in order for me to determine price. I will fill out the primary questions while on the phone with the client and then take time to consider the secondary questions before determining a price. Some clients like to pressure you to give a quote on the phone, off the cuff, before you have time to evaluate the primary and secondary considerations. This usually ends up being a lower price than if you thought everything through. I never give in to this pressure and will always tell them I will be back in touch within the hour if I feel the pressure.

What’s the Value of the Usage?

Now we’ll look at each primary and secondary consideration in detail. How is the client going to use your photography? There are many, many stock photo usages - from web to advertising and editorial. Each usage can be viewed as a unique ‘value’ to the buyer or ‘value received’. When clients license our images, we’re allowing them to use our photo as part of their effort to earn money by selling products and services.

If a client uses my image of Yosemite’s Half Dome for the companies employee handbook that has a certain value to them. If they want to use the image also in a nationwide magazine advertisement, that has another value to them. Which one is going to make more money for them? The more money that a usage is perceived to make for buyer, the more valuable the photograph is to them and the higher the license fee.

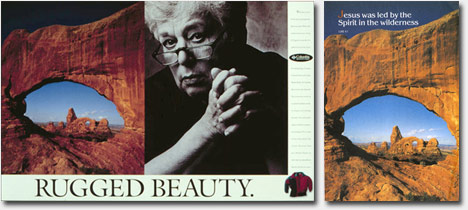

Here are two examples of the same image having a different value to the client, a church bulletin and poster for Columbia Sportswear. The bulletin usage was a pre-determined usage fee of $175 while the poster next to this famous woman had a 2500 print run, yet was high profile and fetched $1000 for a license fee.

Here are two examples of the same image having a different value to the client, a church bulletin and poster for Columbia Sportswear. The bulletin usage was a pre-determined usage fee of $175 while the poster next to this famous woman had a 2500 print run, yet was high profile and fetched $1000 for a license fee.

|

Various usages are broken into categories such as advertising, brochures, editorial, web, point-of-purchase, to name a few. Specialty markets would be calendar, gift cards, posters, travel publications, and so on. These all have different values to the photo buyer. Calendars and cards are a retail item in which a specific print run is produced and sold. You are paid for the production run that year. There is no opportunity to continue to earn income from the photo once the print run is sold out.

Advertising is a different story as it designed to generate income on a continuing basis as long as the ad is running. Ads can be billboards, in magazines, on television, the web, and so on. Ads are higher profile and have more views, similar to page views on the web. The more page views or the greater the circulation, the higher the value of the usage. The same ad with my photo will receive substantially more views in Newsweek Magazine than in Seattle Magazine and so the usage fee would be higher for the Newsweek placement.

Brochures are another high profile usage, but are considered less view’s than advertising. Generally, a brochure has to be picked up, handed to you, or mailed by someone specifically to be viewed. Direct mail is another form of advertising that has a certain quantity of views. A company magazine that is for in-house employees would be a small usage because the views aren’t there and the customer is not receiving the same value for the usage as in an ad.

What is the size of the usage?

The size that your image and how it is placed, also affects the usage fee. A cover of a brochure has greater views or value, than a small thumbnail size on the inside. A double page spread in an outdoor magazine has more value than a ¼ page inside. Your license fees should consider not only how the image is being used, but how big or small as well.

What is the print run or length of time of usage?

Both of these images have been good sellers. The fence image is a great shot, but not as unique as the lightning. I would start by asking 50-100% more for the lightning image for a comparable usage. The image on the left will sell better as a calendar image because it has a sense of place. The lightning will do better as a concept image because it could be literally from anywhere, and it has lots of room for text and would command a higher price.

|

|

Another important factor in calculating a license fee is knowing the size of the print run or in some cases, how long the ad will run. When a customer is producing a brochure, they have obtained quotes on print runs from their printer. This could be 5,000 or 5,000,000 and they will pay for the printing based on the quantity printed. With your photo on the cover, the client is receiving greater value from your image if they print 5,000,000 over 5,000, your price will of course be higher.

In the case of advertising, the client may be placing the same ads in 5 different magazines and they have purchased placement in each issue for three months. In this case the client should provide you the circulation for each of the 5 magazines because they will have determined the circulation ahead of time and reserved space for the ad. If total circulation of the 5 magazines is 4 million, then your price will be the rate for 4 million times 3 insertions. The first insertion is the unique one, seen for the first time by the magazine readers. The next two insertions are not unique because the same audience, magazine subscribers has already seen the ad and subsequent insertions are worth less. So I charge around 40% for the additional insertions, give or take 10% depending how negotiations go. If the amount of additional insertions is more than five, I will lower the cost of additional insertions to 15-25% of initial licensing fee.

Rights Granted: Exclusive or Non-Exclusive

What type of rights does the client want? With non-exclusive there are no restrictions from you selling the image again, immediately, to anyone else, for any use. If they want exclusive, this prevents you from re-selling the image to some degree and that is determined in the negotiations. Should the client want an industry exclusive then that prevents usage by any of their competitors in the same industry for a certain amount of time that you have negotiated. If they want total exclusivity, then this prevents you from selling the image to anyone for the negotiated time frame. Whichever type of exclusive rights the client requests, your price should go up for the loss of potential income from that being removed from a portion or all of the market. I increase my initial price by 2-4 times the basic price to cover exclusive uses.

How unique is the image? One-of-a-kind or dime-a-dozen?

Secondary considerations are very important in calculating the value of an image license. Is your image unique or can the client find something comparable on the net much cheaper? If your client is looking at an image from Mt. Rushmore, is it just like all the other images available or were you there a captured a magic moment in nature? The magic moment will command a much higher price. If you have a spectacular scenic, is it a great calendar/book image or a great concept image?

These two images differ greatly in production value. The petroglyph image was taken on a trip shooting in Arizona. The camping shot was staged, required models I paid, a variety of props and setup time. The petroglyph image sold for $400 while the camping photo was used licensed and re-licensed numerous times for total sales of $800.

|

|

Production Value

You need to also factor into your prices, ‘production value’. For example, if you were in Yosemite and photographed a nice shot of Half Dome, you have little production value going into the making of that image. You walked up and basically took a picture. On the other hand, if you noticed a rock climber about to climb up the wall and you asked if you could photograph him climbing and gave him $20 for a model release, you have greater production value. If you flew to Africa, hired a safari guide to take you into the outback, you have greater production value than going to the zoo or game park. Be sure and consider what it costs you to create an image and consider that in your prices. However, if you live in New York and travel to Utah to shoot Delicate Arch, you may have trouble quoting and additional 50% to your quote as “production value” because your competitors who live closer will not consider that.

Negotiating the Price

The client has provided me all the primary consideration information that I need and I have everything to determine a base price. I currently use the online resource www.photographersindex.com as a guide for aiding in establishing a price. The prices listed are generally starting points from which I then add the secondary considerations or uniqueness, production value, and the rights client has requested. From there I put all the pieces together for the price I will present them. The following are the figures posted on Photographers Index and I will use this image as an example.

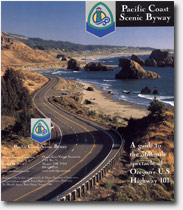

This is a brochure cover and it is regional only. The client plans to print 50,000 and they will be distributed through visitor centers. I went to Photographers Index and they do not have a category for tourism brochures, which are not advertising. I chose magazine, cover, 50K print run. The site suggests a low price of $650, average price of $975, and high of $1300. The client has not requested any rights, so the sale will be non-exclusive. The image is unique, but can be found and shot by other photographers. I settled on a price quote to the client of $850 for the following reasons: low print run, a fairly unique image, tourism related and not advertising, not much production value, and non-exclusive. The client wanted to negotiate and we settled on $800.00.

This is a brochure cover and it is regional only. The client plans to print 50,000 and they will be distributed through visitor centers. I went to Photographers Index and they do not have a category for tourism brochures, which are not advertising. I chose magazine, cover, 50K print run. The site suggests a low price of $650, average price of $975, and high of $1300. The client has not requested any rights, so the sale will be non-exclusive. The image is unique, but can be found and shot by other photographers. I settled on a price quote to the client of $850 for the following reasons: low print run, a fairly unique image, tourism related and not advertising, not much production value, and non-exclusive. The client wanted to negotiate and we settled on $800.00.

|

This image is very unique and if the client wanted to use it for the above uses, I would add between 50-100% to the price.

|

|

The client came back with a request for more uses as a tourism related advertisement, running nationally in 4 travel magazines with a combined print run of 2.5 million. The suggested low price is $1200, average $1850, and high $2500. Because it is tourism related and thus a lesser value than an advertisement to sell a product, I quoted the client $1600 and we settled on $1500. Now a west coast travel magazine has seen the ads and wants to use it in an editorial piece in the magazine for the summer issue and at ¼ page. They are only the west coast and have a circulation of 300,000. The index suggests that the low price be $175, average $300, and high $425. Since it was a regional use instead of national, the agreed price was $250 for one time, non-exclusive, editorial.

More Negotiating

You have looked at all the variations regarding your photo and the uses, presented it to the client and they balk at your price. If they don’t like your price, be prepared to explain why it is worth the price you quote. If they still balk, I ask “what’s your budget”. See what the answer is. If they are offering a price that is ridiculously below your quote then be prepared to lose the sale. Stand your ground. Both you and the client need to compromise, they need your image and you need a sale. If you quote $400 and they say $250, meet them halfway at $325 plus a credit line. You may be surprised how many actually call back and say that the client O.K.’d the price you quoted and a sale is made.

Credit lines are overrated and generally have little value to the photographer. They rarely translate into more sales or request, but make for a good way to lower your price while saving face. You want to make a sale and are willing to go down on your price and requesting a credit is one way of giving a little by getting something back.

If they say they can get the image for a third of your price on the internet, then I say go ahead and buy that one because it is clearly a better value and again it is amazing how many actually must have your image and will pay the price. Occasionally there is a publisher out there interested in obtaining lots of photography and paying on a royalty basis. I have accepted these terms of payments from some established publishing companies and it has worked fine. You may be invited to participate in a royalty program from new or start up companies who do not have the resources to pay upfront for licensing photography. These are much more risky because there is no guarantee the company will survive nor that you will get paid. Look very carefully at these potential projects and do your best to evaluate all aspects of the license agreement they present to you.

Non-Profits

You may at some point find yourself negotiating with a non-profit or asked to provide an image pro-bono. Letting images be used by non-profits and whether or not to charge depends on the information they provide. Some “non-profits” have the highest paid executives, are in spendy office space, and have substantial ability to generate income. I for the most part will inform them that “I am not a non-profit and need to charge for my work”. This is done by looking at the base price and then knocking a little off for the “non-profit” aspect.

An ad agency called once and requested the use of an image “pro bono” (free) for a project they were working on. My naïve impression was that if I was asked to donate my work that everyone else had also. I found out later that the agency received a token fee, the printer got full price for printing the poster, and that I was the only one who donated fully. I have since refused to provide anything for free without proof that all parties donated for free as well. Otherwise I want a slice of the pie.

This is a very common occurrence where the photographer is asked to donate probably because there is such a huge supply of images. Many fall for it. Your work is worth something! If they want it free, maybe there is a trade of value. I have traded my images for nights at lodges and free dinners. Do your best to get something for yourself.

Reuse of an Image

If an ad that has been running is successful then they may get back in touch with you and wish to renew the license agreement again. Since I am in the business of making money selling my product I feel obligated to get as much as I can. A good starting point is to quote 75% of the original fee for the same usage again. Sometimes I am forced to go to 50% and will agree to do this if they have lengthened the time that the ad will continue to run. The same goes with brochures or anything priced by the print run. If they are printing another 15K of the brochure, I try to re-license for 75% of my original fee.

Invoicing

The last step in negotiating your transaction will be the invoice. It is imperative that you state the terms of the sale in your invoice or you could be out some potentially good money if the client thinks they can keep using your photo because you did not spell out the terms.

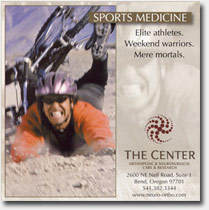

For this image I negotiated a two month usage for local magazines with a small circulation. The book price was $400 but because I have extensive Photoshop work on this image I was able to get another $175 for its production value. My invoice stated the following:

For this image I negotiated a two month usage for local magazines with a small circulation. The book price was $400 but because I have extensive Photoshop work on this image I was able to get another $175 for its production value. My invoice stated the following:

Stock photo usage for THE CENTER, one-time non-exclusive rights of image # 177-389 mountain biker crashing, to run ¼ page, editorial only, in XXX magazine and ZZZZ magazines for two months through August 2004.

|

Finally

There are so many factors to consider in pricing your imagery for licensing. By following a few steps and understanding how your image fits in the market, how much value your client will receive from your photo, and the going rate for such a usage, you can receive a fair price for your work. Stock photography cost money to produce and needs to generate income that is greater than those costs. It is important that each images value be determined and that a client pays for that value. By carefully evaluating your work and receiving fair compensation for it, you will have the resources to continue to follow your passion as a landscape and nature photographer.

Comments on NPN nature stock photography articles? Send them to the editor.

CB-NPN 1783

Charlie Borland has been a professional photographer for over 25 years. Based in Oregon, he shoot both locally and nationally, traveling extensively for a wide range of clients, some of which include: Xerox, NW Airlines, Fujitsu, Tektronix, Nike, Blue Cross, Nationsbank, Texas Instruments, Pacificorp, Cellular One, Early Winters, among others. He has received numerous awards and recognition for his photography.

His outdoor, landscape, and adventure photography has been used extensively throughout the world in hundreds of calendars, advertising and marketing campaigns, and magazines including: National Geographic Adventure and Traveler, Outside, Women's Sport and Fitness, Newsweek, TV Guide, CIO, Sports Illustrated for Women, Time, Backpacker, Sunset, American Photo, Outdoor Photographer, Eco Traveler and Southern Bell, to name a few.

Charlie has been heavily involved in the stock photography business, owning a stock photo agency for 8 years before merging with Definitive/FPG and later Getty Images. He is currently Director of Photography at www.fogstock.com an online agency he co-founded.

He also directs Aspen Photo Workshops where he conducts numerous workshops including: Making Money in Stock Photography, Travel Stock Photography, and several Adventure Sports and Cowboy Photo Shoots for stock photographers.

|