As spring slowly awakens life in the high plateaus, I went on my first solo backpacking trip of the season. While nights at home still dip below freezing, the canyon country is already warm and welcoming. Now back at my desk I revel in the sweet fatigue that follows such excursions; remembering with vivid clarity the brilliance of the new foliage, the warm glow in the narrow sandstone passages, the swirling cascading songs of canyon wrens in the high cliffs, and the velvety silence at night, interrupted only by the hushed gurgle of the nearby creek. I miss it. All the time. When I’m not there, that is.

Though I am fortunate to live in what to many would be wild country, there is still the palpable shift between time spent living – as a physical, emotional, being – and the astoundingly bizarre artificial reality of modern society, business, politics, the Internet, and other contrivances of the human mind. It is a sad and painful disconnect at times, made worse by the fact that such experiences can only be truly shared with those already familiar with them. Words fall frustratingly short of describing what it means and why it is important to someone who doesn’t already know.

I left home early in the afternoon and drove in the general direction of the canyon I planned to visit. The choice of time and place were not random. The date is an important anniversary, though not one relevant to this narrative. The place, beyond being one of the most beautiful places on Earth, was the setting for memorable times in my life. I wanted it all to converge. I wanted to think about it all and put it all in perspective and tie it all together in a place I love more than any other.

The road here was recently “improved,” though is still unpaved. Still, what once required a long, bumpy ride in a high-clearance vehicle, is now possible in any passenger car. Justification for such projects almost always touts increased visitation, a boost to the local economy, and all other derivations of the ultimate in human endeavors: growth. You may note that terms such as “economic growth” are never placed in the context of a counterbalance. It’s always good, and the more of it the better. Conspicuously absent from such decision frameworks are terms such as spirit, silence, solitude, inspiration, and wildness. The closest you will find is “recreation,” which is far from the same.

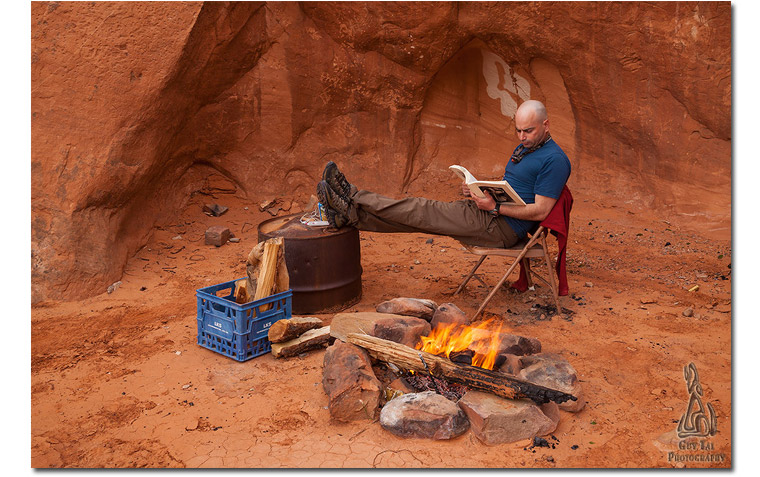

I set up camp among the red rocks. Local cowboys left a folding chair and bullet-riddled barrel here, which I made use of. On this first evening I could camp by my vehicle, which usually means a nice fire and a good dinner. As the sun set, I read favorite excerpts from the Daybooks of Edward Weston. What a fascinating man. Among the pages a life unfolded: a passion for photography, great love for women, for places, for family, and for art. In his work, Weston celebrated life and its expression through his unique brand of imagery. Still, photography is far from being the only theme in the narrative. Every few pages, glimpses into the life of an artist told the story of struggling to pay the rent, pandering to the poor tastes of patrons, not being able to afford a measly $75 for medical treatment for an injured son. Weston was not Ansel Adams. He never became rich off his work, and never lived as if he wanted to. In that sense, to me, he was more of an artist (though he disliked the term) than so many of his peers. His life was his work, and beyond it he preferred to be left alone to his beloved places, negatives, and contact prints. More income meant less time pursuing his photography, and the balance he struck between the two was closer to what I chose for my own than to that of Adams or Stieglitz or others.

Weston passed away with just a couple of hundred dollars in his bank account, never selling a print for more than $250. Some years later, two of his prints sold at auction for more than a million each. Just recently, a limited edition book of his work went on sale at a whopping $250 a copy. Weston himself never limited his print editions and would likely never have been able to afford this book. With such ironies, the gap grows ever wider, deeper, and darker.

As darkness set, flames from my small fire offered a hypnotic spectacle of dancing light on the red rocks. The moon climbed slowly in the night sky and, one by one, more celestial friends appeared. Venus was first, and, not too far, aldebaran – the follower – kept watch of the seven sisters of the Pleiades. The belt of Orion stayed visible for just a few minutes before venturing beyond the edge of the cliff. Ancient worlds whose light kept me company on countless such nights for so many years.

I spent the next morning slowly arranging my large backpack, thinking with some amusement of people I know who pride themselves on being “ultralight” backpackers – people who will stop just short of removing essential body parts in order to save a few ounces. Not me. I’m quite fine with moving a bit more slowly and carrying a couple of extra pounds for such small pleasures as a good hot dinner, small treats that I knew will taste better on the trail than anywhere else, a good book, notepad, fresh ground coffee and a French press, fresh baked bread, and even a small flask of fine tequila. Ultralight hiking is for masochists.

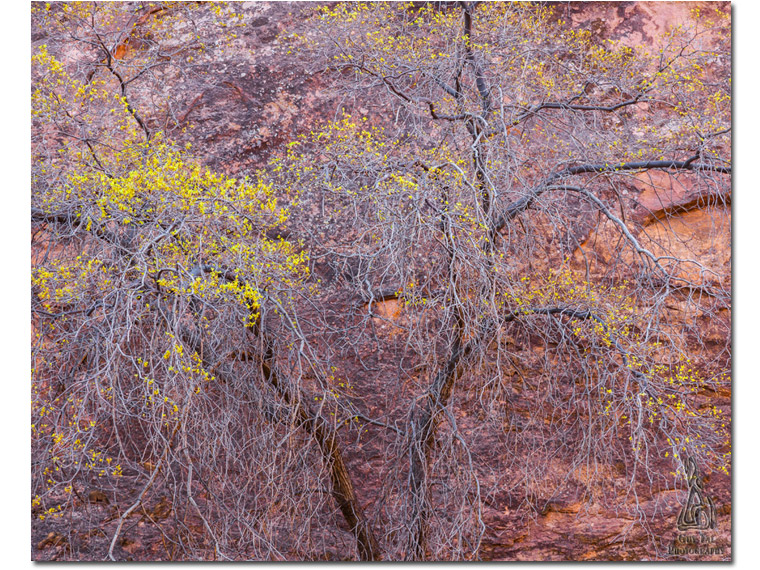

I started my walk around mid-morning on a gorgeous early spring day. Some early bloomers - milkvetch, paintbrush, gilia, and others - were already in flower, adding dots of vibrant color to the desert brush. Many of the trees were adorned in vibrant fluorescent green buds. Everything felt and smelled and sounded joyous, blissfully free of the sounds of engines and electronic gadgets and human banter. I knew I could count on having this remote canyon to myself and took great joy in every step carrying me further from the road.

It didn’t take long to realize that the canyon was also used by cattle ranchers. Cow excrement was everywhere, as were eroded paths through the delicate ecosystem. Who in their right mind would consider such a paradise appropriate for grazing? Not the cows, I bet.

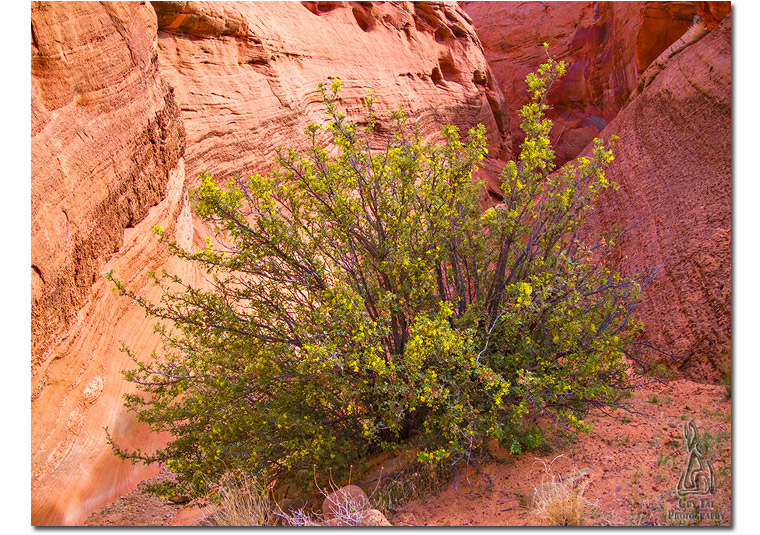

About a mile into the canyon I was in for a very pleasant surprise. A delicate sweet scent filled the narrow passage – one I had not smelled in months. I recognized it instantly – a member of the barberry family known as Fremont’s Mahonia. Many of these bushes grow here and the delicate aroma stayed with me for much of the trip, conjuring wonderful memories of other canyon spring hikes.

This canyon is unique in more than one way. Other than the steep red cliffs so iconic of this region, this particular place also has a rich Native American legacy. Many of the alcoves above its channel had not been fully explored, and on occasion a rare find will present itself, stop me in my tracks and send my imagination soaring. Today I took some time to explore a small side canyon and was rewarded with an exquisite discovery indeed: a metate (mortar) with mano (grinding stone) still in it, just as they were left by those who once lived here hundreds of years ago. The area was thick with scrub oak, suggesting that the metate may have been used to make acorn flour. I placed my hand on it, wondering what other human hand touched it before mine. I stood there for a while, surveying the area, trying to imagine what life was like for those whose home it once was. Other than the cows, chances are it looks very much the same to my eyes as it did to them.

My wife once asked me if I thought “they” found these places beautiful, or if it was just a common life to them. I think they did find it beautiful. Much of the meager evidence they left celebrates natural phenomena, far beyond mere utility. And, after all, they were as human as I am, having the same brain and the same ingrained appreciation and awe for such places. I was not born here, but I found these canyons exquisitely beautiful since the first day I saw them.

Farther down the canyon, a large wall juts up into the sky, hundreds of feet tall. Along its base are some of the most fantastic petroglyphs I have seen anywhere, some as high as fifty feet off the ground, carved into the blue/purple desert varnish. This was a place of power, of spirit, of ritual. It is evident in the rock art but also in the feeling one gets from standing in the sandy clearing at the base of the commanding cliff. I can understand why the natives chose it. People, bighorn sheep, owls, snakes, and large anthropomorphs told stories whose meaning is now long forgotten.

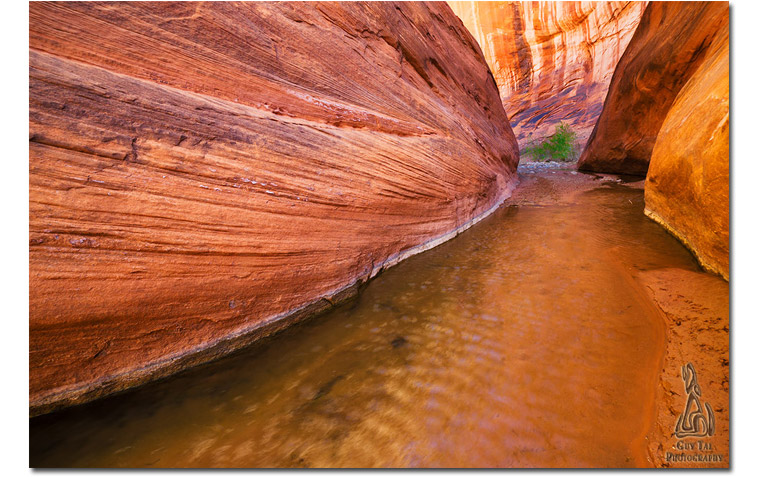

A couple of miles further started the riparian portion of the canyon. A small crystalline stream flowed at my feet and will accompany me for the rest of the hike in. Another mile or so brought me to a huge alcove – my home for the next couple of days. I set up my tent and arranged my camp in the shadow of an old cottonwood, below the towering slickrock wall. A curious collared lizard watched me as I arranged my belongings and hung my food bag from a high branch to keep it away from rodents. I put together a small backpack and left camp for the afternoon to explore the lower regions of the canyon – some of the most spectacular stretches of slotted narrows on the Colorado Plateau

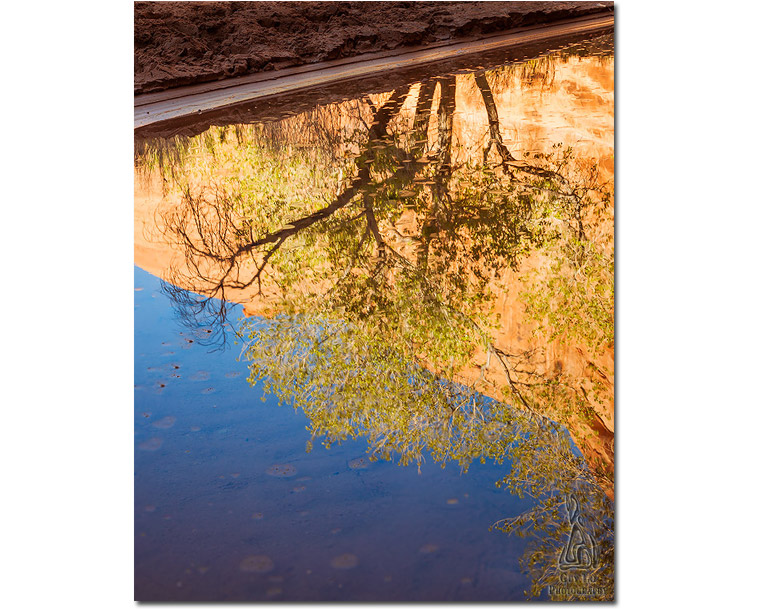

For the next few hours I was in a state of waking dream, walking and wading through twisted passages, bathed in golden light reflecting off the steep walls. The budding cottonwoods and willows combined with the wet earth to fill the air with a rich scent that defies description. I stopped occasionally to study patterns and shapes, a young gopher snake, and countless lizards. When I wasn’t walking, the only sound was the trickle of water rushing along the smooth slickrock. I thought of the things I came here to remember and to honor – people and animals and experiences and events. It’s been so long, and the weight of the years is undeniable. In so many ways, our lives are but a blink of an eye, yet our capacity to bear the weight of emotions and memories has a limit measured in pain. To live longer, we must either learn to feel more or forget more; and I can’t forget.

I photograph, not to create art, but to hold tangible what little I can of the experience. There will come a day when I can no longer make this journey in body, but I know I will want to do so many times over in mind and spirit.

My first memory of life was several decades and thousands of miles away. It’s easy to dismiss my being here as a coincidence but, being the lay scientist that I am, I cannot discount the overwhelming odds against it, now, by myself, in this remote and strikingly beautiful vestige of remaining wilderness on Earth. My rational self refuses to accept it, but somewhere in me a little voice keeps saying that it has to mean something, and it will not be silenced.

I was reminded of a recent conversation with a friend. When I told him of my then planned trip, he said he always wanted to see this place, but “life got in the way.” Beware of life getting in the way of living.

I slowly made my way back to camp, arriving late in the afternoon, shortly before sunset. I set about cooking my dinner in the last light of the day. Indian bean curry, French bread, avocado slices, and a couple of shots of Corralejo reposado. Tired from walking, the food tasted wonderful and prepared me for a restful night as my mind continued to wander.

I never understood the expression “not a soul” to describe places where humans are absent. Here, it seems, there were more souls than living beings. From ancient crustaceans whose shells and skeletons became the limestone pebbles in the creek beds, through many forms of life no longer in existence, early humans on the heels of the last Ice Age, followed by thousands of years of various desert-dwelling cultures and all the way to an immigrant photographer marveling at bits of light launched towards the Earth hundreds of years ago only to paint a little bright dot on my retina at this point in time. More souls than I could ever hope to count, each with a life story greater than any novel.

The next day was spent in further explorations of the canyon and its tributaries. By this time I was no longer even thinking of life outside the glowing walls. This was my world and in it was more mystery and beauty than I could hope to experience. Little else was needed to feel happy and grateful. Wrens were chattering and singing in the cliffs; butterflies – admirals and mourning cloaks – fluttered around the placid pools; large beetles buzzed around the cottonwood canopies and new foliage; lizards darted around, making a racket in the dry fallen leaves; ravens floated above sometimes so close that I could hear their wing beats. The limestone pebbles revealed the occasional fossilized shell. Farther down the canyon, fresh trees felled by beavers diverted the flow into a large pool. Everything was full of wonder and beauty and innocence. This is a place of no pretending. You are either part of it all, or a complete stranger.

Another evening, another night, more discoveries and revelations, sadness and joy, breakdowns and affirmations.

The following morning I took my time breaking camp, pumping water and working up the will power to hoist a 50lbs. pack for the long trek back, now even more tired and sore. That’s OK. I’m not in a hurry. It will take as long as it takes. On the way back I paid more visits to the ancient dwellings, the metate, and the fragrant Mahonias, and scrambled out of the canyon.

My trusty pickup waited among the tamarisks, now a bit dusty. I grabbed a cold drink from the ice chest in the back, sat on the tailgate and savored the last of the experience. A couple of miles down the road I stopped to chat with a couple of young kids carrying large packs. Their clothes were filthy, they were tanned and unshaven and smiling (as I’m sure I was). They had just come out of their first canyon hike and I could see the glimmer in their eyes as they talked about it. I remember my first time, almost twenty years ago. It changes you. In a good way.

Have you ever felt true and profound gratitude? Not just being thankful for a small favor; I’m talking about an overwhelming sense that at this exact moment in time you are, without a doubt, the happiest, luckiest form of consciousness in the entire universe.

Here I was again, driving down a long dusty empty dirt road, kicking up a small plume of dust that floated into the sagebrush plains; watching a hawk hover silently above; and the majestic ancient cliffs beyond; seeing clearly to the high plateau that is now my home… and feeling truly and profoundly grateful.

Guy Tal - NPN 440

|

Guy Tal is a professional photographer and author residing in the state of Utah, in the heart of a unique and scenic desert region known as the Colorado Plateau. Guy teaches and writes about the artistic and creative aspects of photography and guides private workshops and individuals seeking the beauty and solitude of the canyon country. More of his works and writings can be found on his web site and blog at guytal.com. You may also follow Guy on Facebook or Twitter.

Guy Tal is a professional photographer and author residing in the state of Utah, in the heart of a unique and scenic desert region known as the Colorado Plateau. Guy teaches and writes about the artistic and creative aspects of photography and guides private workshops and individuals seeking the beauty and solitude of the canyon country. More of his works and writings can be found on his web site and blog at guytal.com. You may also follow Guy on Facebook or Twitter.

Guy is the author of three e-books, Creative Landscape Photography, Creative Processing Techniques, and Intimate Portraits of the Colorado Plateau.