|

|

Access for All?

Text and photography Copyright Niall Benvie "Location, location, location" may be the mantra of the estate agent but it could equally be that of the nature photographer. A good site is worth more than all the most up to date equipment, more than a library of books on technique. It is where you can practise all you have learned and get full use of the gear you own. This is where you develop as a photographer.

The importance of developing relationships with private landowners has a particular resonance in Scotland at the moment as the Land Reform (Scotland) bill, published on the 28th November 2001 by the Scottish Executive, makes its unsteady way through the Holyrood Parliament. The bill is intended to provide a framework for more liberal access rights to privately-owned land as well as granting crofting communities the right to buy the land they currently tennant. Understandably, perhaps, the Scottish Landowners Federation finds much to oppose in this and and other provisions and the Scottish National Farmers' Union, whilst welcoming amendments made at the draft stage, still has a number of reservations. Two important concessions have been obtained by these organisations which have a direct bearing on our work as photographers. The first provision prevents access for the commercial use of someone-else's land. That seems perfectly reasonable until you consider that this clause, if passed in its present form, is so sweeping that it would, amongst others activities, prevent anyone taking a "professional" photograph on someone else's land without first obtaining written permission and / or paying a fee to to so, at the owneršs discretion. In practice it might be very hard to prove that a picture was taken after the enactment of the legislation but the point is that the principle would exist in statute. While this is of concern only to professional photographers, more worrying for every one is the power to be granted to local authorities to stop people from taking access at night. Clearly, this is intended to protect landowners from the devastation (and I've seen it first hand) caused by uninvited raves and New Age gatherings. But equally, as currently framed, photographers setting out for a long walk into a location for dawn, would be subject to the same restrictions. At the time of writing (mid-August 2002), I have received assurances from the Minister, via my MSP, that the needs of professional photographers will be taken into account when legislation is being finalised for enactment. But whether or not the lobbying for the clarification of these proposals by groups as diverse as photographers and tour guides finally prevails, what is clear is that those individuals who are known and trusted by landowners are less likely to be affected, either way. A few landowners have expressed to me, quite earnestly, the belief that they "own the view" - to which I respond that I'm photographing "their view" inspite of, not because of, the way they've managed it. Most farmers Išve worked with have a more sharing attitude - taking a photograph, after all, does nothing to diminish their "resource" or its agricultural utility and few are themselves able to exploit its creative potential. Strictly speaking, if we adhere to the letter of current Scots Common Law, we are commiting no offence by simply being on someonešs land; in this sense there is no law of trespass. Nevertheless, the landowner is entitled to ask us to leave and to use "reasonable force" to achieve this end. Individuals can be excluded only once an interdict (in England and Wales, an injunction) has been taken out against them; failing to observe its terms opens the way for criminal prosecution. But quoting the law is no way to foster good relations. Whatever form the Act finally takes, it is unlikely to be as universally accepted or acceptable as the principle of allemannsretten practised in Norway and other parts of Scandinavia. Allemannsretten - "every manšs right" - strictly codifies in law the rights and obligations of landowners and the public alike against the backdrop of a constitutional encouragement of "Friluftslivet" - the open air life - which is at the heart of Norwegian identity. According to Dr Duncan Halley, a Scottish biologist who now lives in Norway, "One of the most pleasant aspects of enjoying the outdoors in Norway is the lack of a vague feeling of foreboding when walking anywhere which is not clearly open to the public, familiar to most walkers in Scotland."

Sceptics may argue that owing to Norway's much greater landmass, such a system is not transferable to Scotland. But in reality, once Norway's largely uninhabited wild mountainous areas are discounted, the population density of the two countries is similar. The real difference, I suspect, is rooted in a deeper polarisation of town and country in the UK which can be explained, in part, by our longer industrial history and the legacy of a feudal system of land ownership. The urbanisation which accompanied industrialisation is largely a postwar phenomenon in Norway, so town dwellers are often no more than two or three generations removed from a more elementary rural lifestyle. Most Norwegians own a hytte or summer cottage to which the family goes at weekends in summer and autumn. They remain, so far at least, an outdoors people. The same applies in the Baltic states and it is striking how Riga on a Saturday, rather than filling up with shoppers as you would expect to see in Edinburgh or Birmingham, is much quieter than during the week as people head off to their cottages in the country. One of the consequences of this fracture in the UK is a loss of common knowledge of how the rural economy works, how the people there get a living and even what mushrooms and berries are good to eat. But it is a break that cannot be healed by exclusion and denial of the opportunity for people to experience nature at first hand rather than in the artificial confines of "visitor friendly" areas. I think the frequent reluctance to allow people the chance to reconnect with wild nature is most depressingly exemplified in attitudes to wild camping, summarised neatly in an extraordinary sign I photographed in Glen Lyon which read "For Conservation's Sake - No Camping Please." Far from being viewed as a way of getting back in touch with nature, of developing empathy through experiencing the elements directly, this hints that camping is a disreputable pursuit. I think I understand why some people believe this, however, and wish they would be less coy about their unwillingness to entertain campers. Many, it seems, fail to bury their dung, or indeed exercise much common sense about where to leave it, where to light fires or dispose of rubbish. I experienced this during my farming days and I see it again as travel the country in my campervan. If you're not going to use public toilets (and many in the Highlands make the outdoor option vastly preferable) dig a hole, well away from water courses. Anything else is just anti-social and gives landowners justifiable cause to exclude campers. Getting back to nature doesn't mean acting like a savage. Note: My thanks to Roddy McGeoch, Fyfe-Ireland, Edinburgh and Dr. Duncan Halley for their advice. Niall Benvie - NPN 018 Comments on NPN nature photography articles? Send them to the editor. |

|

|

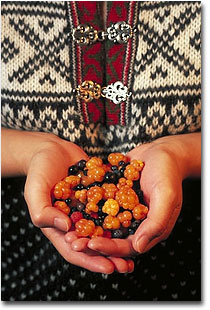

Sachiko holding blaeberries, rasps and cloudberries. Good food tastes

even better when eaten out of doors and more so when youšve gathered it

yourself. The Norwegians take this elementary pleasure for granted but it is

a privilege relatively few British people enjoy nowadays. Nikon F4, 90mm,

flash and tungsten light, Velvia.

Sachiko holding blaeberries, rasps and cloudberries. Good food tastes

even better when eaten out of doors and more so when youšve gathered it

yourself. The Norwegians take this elementary pleasure for granted but it is

a privilege relatively few British people enjoy nowadays. Nikon F4, 90mm,

flash and tungsten light, Velvia.

Red squirrel on frosty bough. I found out about this private garden

visited by red squirrels after placing a notice in our regional newspaper a

number of years ago. Sadly, the squirrels no longer come, having been

displaced by the advance of greys from the west. Nikon F4, 300mm + x1.4,

flash set to -1.7ev, Fuji Sensia 100.

Red squirrel on frosty bough. I found out about this private garden

visited by red squirrels after placing a notice in our regional newspaper a

number of years ago. Sadly, the squirrels no longer come, having been

displaced by the advance of greys from the west. Nikon F4, 300mm + x1.4,

flash set to -1.7ev, Fuji Sensia 100.