At various points when photographing in the field I'm sure we've all run into our share of characters. I know I have. In fact, I think I've run into more than my share. Some of these folks have been photographers themselves, but for some reason, the most memorable encounters I've had in the field have been with non-photographers. I always try to be pleasant and I'm usually happy to engage these folks, as long as I'm not deeply involved with the subject matter. Sometimes, however, this isn't as easy as it seems. I've compiled a diary of my favorite in-field experiences. Here they are in no particular order.

Episode 1: Digital Film

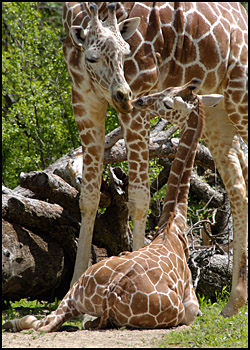

I'm a landscape photographer and I've always conceded that you could fit what I know about wildlife photography in a thimble and still have plenty of room left over. Every once in a rare while in the field, an animal will be magnanimous and pose for me. Even more rare is when I go looking for that kind of shooting opportunity - at the zoo.

In late April 2004, I brought my newly purchased 80-400 Nikkor VR lens to the Brookfield Zoo in suburban Chicago. My mother is nutty about giraffes and I thought this would be a good opportunity to use the new lens, along with the D100 I’d started using the previous fall to capture some images that I could print and give to her as a Mothers Day gift. It was a weekday, and with school still in session, the crowds were fairly thin. Even though the light wasn’t the best, it was a good opportunity to produce the kinds of images I was interested in.

The Nikkor 80-400, when mounted on a tripod and racked all the way out with the hood on, is a pretty impressive-looking lens to the uninitiated. While I was fiddling around in front of the giraffe enclosure, a man wandered over.

"That’s quite a lens," he said.

I'd already captured a decent set of images, so I disengaged from the rig to talk to him.

"It's a fairly long lens," I said. "But it’s nothing remarkable."

"Is that a digital camera?" he asked.

I explained that it was. He said that he was using a digital point-and-shoot himself and hoped to get a digital SLR soon. We talked about cameras and lenses a bit and while he clearly wasn’t an expert, he seemed fairly well informed.

After chatting for a few minutes, the conversation hit a brief lull.

"So," he said, breaking the silence, "what kind of film have you got in that camera?"

There was a long pause.

"Um…" I said, trying to recover my own equilibrium and not embarrass him at the same time, "it is a digital camera."

After another long pause, he looked at me and said with the slightest hesitation in his voice, "Yeah, so, what kind of film are you using?"

What could I say? I felt bad for him.

"The images are captured digitally," I answered. "There is no film."

He got very red in the face and turned and walked away without another word.

Episode 2: Disaster Insurance

I don’t usually do all that much shooting in the summer, but we had a very wet June and July in northeast Illinois in 2007, which produced a bumper crop of wildflowers. In late July, I spent some time shooting the wildflowers in the restored prairie at the Danada Forest Preserve in DuPage County.

Brief background on my equipment: when I became really serious about photography a number of years ago, I decided that I needed a second camera body as a backup for shooting on photo excursions. The reason for this was, what would I do if I was in some remote location if the only camera I owned went on the fritz? I used a Nikon film camera to backup my first D100, purchased in the late summer of 2003 and I currently have a pair of D200s. Since I have two identical bodies, I carry both in my backpack and use them both. It minimizes the amount of lens changing I have to do in the field.

of D200s. Since I have two identical bodies, I carry both in my backpack and use them both. It minimizes the amount of lens changing I have to do in the field.

Back in the Danada Forest Preserve, it was early evening and the light was changing by the minute, so I was trying to work quickly. I was switching between close-ups of Prairie Coneflowers and wider landscape images of a field of a wide variety of summer wildflowers. I had my macro lens mounted to one camera body and a wide-angle lens mounted to the other. I was pulling one setup off of the tripod and replacing it with the other. My position was only 10 feet or so off of a fairly heavily utilized hiking/biking trail, so I was in plain view of the occasional passerby. One gentleman happened by as I was wrapping up with the camera that had the macro lens attached. He watched me pull off the first camera and replace it with the second. He was in my peripheral vision as I was doing this, so I was vaguely aware of his presence.

It turned out that he was a Type A personality.

"Are you a professional photographer?" he asked.

I hear that a lot. It typically is a function of having a tripod. As someone who sells prints here and there but has no intention of trying to make a living from photography, I have a stock answer to that question. In this case, however, I really wasn’t interested in engaging in chit chat. I had a series of images I was trying to take before I lost the light and I didn’t need the distraction of a conversation. Still, I tried to be polite, hoping that he’d get the message that I didn’t want to talk by trying to continue what I was doing photographically while speaking.

"Semi-professional,” I said. “I sell some prints, but I have a day job."

"So you’re not a full-time professional?"

“No,” I replied, as I peered through the viewfinder trying to fine-tune a composition. I figured that would be the end of the conversation. I was wrong.

"So what do you need two cameras for? Seems like a real waste."

This guy wasn’t going away. I briefly explained the backup and lens swapping principles, emphasizing the former. Again, I figured that would end the conversation and I went back to composing my shot. But I was wrong again. The conversation wasn’t over.

"Have you had a situation where a camera was broken on a trip before?"

"No," I said.

"Then why go to the trouble and expense of having a second camera? It doesn't make any sense."

Apparently this guy thought that because I hadn’t had a problem in the past that I’d never have one in the future or that I shouldn’t be prepared for the possibility or both. Rather than relating one of several stories about acquaintances of mine who have found themselves without a camera when in remote locations, I decided to give him an example he could identify with directly.

"Do you own your own home?" I asked. He did. "Do you have fire insurance?"

"Of course," he said.

"Has your home burned down in the past?"

End of conversation. He resumed his walk and I got my shot.

Episode 3: You’re Taking a Picture of That?!?

Northeast Illinois will never be regarded as one of the planet’s garden spots for nature photography, but there are some very nice niche locations if you know where to look. One such spot is the Morton Arboretum, in DuPage County. With a variety of plants and distinct ecosystems, interesting photo opportunities abound all year round. The Arboretum is only about 15 minutes from my residence in the Chicago area so I head there with regularity.

In late April of 2007, sections of the arboretum are thick with Virginia. I waited for an overcast, relatively windless day and rushed over to the arboretum to take advantage of the conditions. I know the good  wildflower locations from experience and immediately went to the best spot to spec out some interesting compositions. I had sized up a hillside covered with bluebells, composed a shot while handholding the camera, as I typically do, then went about setting up my tripod to complete the shot. My shooting location was only about 25 feet from the one-way paved road that winds through the arboretum, with my back to the road. As I was fine tuning the composition with the camera mounted on a tripod, I heard a car pull up behind me on the road and stop, with its engine idling. I didn’t pay much attention since cars drive by on the road regularly, but after a few moments I heard a voice shout out.

wildflower locations from experience and immediately went to the best spot to spec out some interesting compositions. I had sized up a hillside covered with bluebells, composed a shot while handholding the camera, as I typically do, then went about setting up my tripod to complete the shot. My shooting location was only about 25 feet from the one-way paved road that winds through the arboretum, with my back to the road. As I was fine tuning the composition with the camera mounted on a tripod, I heard a car pull up behind me on the road and stop, with its engine idling. I didn’t pay much attention since cars drive by on the road regularly, but after a few moments I heard a voice shout out.

"What are you taking a picture of?"

I looked behind me and saw a man leaning out the open driver’s side window of a car. I then looked around to see if he might be talking to someone else. I didn’t see anyone. I looked behind me again.

"Are you talking to me?"

"Yeah," he shouted over the running engine. "What are you taking a picture of?"

I looked back to the camera again and briefly surveyed the beautiful setting. Then I turned back in the direction of the car.

"The scene," I said.

"What scene?"

"This scene - with all the wildflowers," I said.

"Oh," he said.

Long pause.

“How come?” he asked.

How come?!?! How come I was taking a picture of this beautiful scene?

"Oh, no reason," I said. "No reason at all."

The more quickly some conversations are ended, the better.

Episode 4: Drive-By Shootings

I spent a week at Great Smoky Mountains National Park in October 2004, at the peak of the fall color season. I spent the entirety of one overcast day along the one-way Roaring Fork Road. The weather was perfect for shooting the streams and woods. Because this was at the peak of fall color, the park was crowded - very  crowded, in fact.

crowded, in fact.

At one pull off along the road, I found a shot of Roaring Fork that I felt really captured the essence of the place. The shot required me to set up on a small bridge that crossed the creek, with one of my tripod legs on the bridge and the other two legs near the edge of a rock. As I said, the park was crowded, and the road was packed. The bridge was so narrow that cars couldn’t pass by if I remained in my shooting position. So, every time a car came by, which was often, and they frequently came by in bunches, I had to lean forward, pivoting the tripod on the front two legs to get out of the way. This was a bit frustrating, but I couldn’t very well hold up traffic while I took my shot. In reality, I was in the way of the oncoming cars. It was a road, after all.

In any case, because of this complication, it took far longer for me to complete the shot. It was somewhere between five and ten minutes before I was able to meter the scene properly, get in place, fine tune the composition, and get the shot without a car interrupting the process. During this time, at least 50 vehicles passed by me on the bridge.

What I found particularly interesting about this experience was how many people who passed by me in the vehicles took pictures of the scene themselves. I would guess that it was at least one-half. The vehicle would approach, a point-and-shoot camera would emerge from the passenger’s side window, the built-in flash would go off, and they’d move on. Some of the vehicles would come to a brief, but complete halt before shooting. Others would just slow down. I referred to these as "drive-by-shootings."

I had the opportunity to hear some commentary on occasion. My favorite remark was when I heard a male driver tell his wife (or significant other), "Wait 'til we tell people back home that we took this shot without stopping. They’ll never believe it!"

Oh, I’m pretty sure they will.

Episode 5: Moose! (but no Squirrel)

In May 2006, I spent a week at Acadia National Park in Maine along with fellow NPNers Danny Burk, Dan Borzynski, and a handful of other photographers. We had a great time and came back with many wonderful images and a story or two.

On the morning of the final full day at Acadia, we split into two groups with a rendezvous time and place set - Beaver Dam Pond, not far from the town of Bar Harbor on Mt. Desert Island. My group arrived at the location first and we had a bit of time to kill before meeting our compatriots. It was a very windy day and since I was the only participant shooting with something other than a large format camera - the bellows of which become a  sail on blustery days - everyone else stayed in the car, pulled over to the side of the one-way loop road to gab about bellows compensation and reciprocity failure. I meandered about with my D200 and tripod.

sail on blustery days - everyone else stayed in the car, pulled over to the side of the one-way loop road to gab about bellows compensation and reciprocity failure. I meandered about with my D200 and tripod.

Windy as it was, I avoided conventional shots since freezing the colorful spring foliage (you read that correctly) would be impossible. Instead, I focused on a few offbeat compositions. I was experimenting with how different shutter speeds rendered the ripples and sky reflections in the pond, pointing my 80-400 mm lens down at the surface of the water. The significance of this final, seemingly painfully obvious, point - that the lens was pointed down - will be made apparent shortly.

Suddenly a car roared up behind me and screeched to a halt. I turned my head in time to see a woman jump out of the passenger side door and race up to me.

Bubbling with excitement, she could barely contain herself sufficiently to breathlessly ask – or yell might be more accurate, "ARE YOU TAKING PICTURES OF A MOOSE?!?!"

Rarely, if ever, have I been so taken aback. I was so shocked by this episode that I was dumbstruck for several seconds - though it seemed much longer at the time. I actually remember briefly looking around, trying to be sure she was actually talking to me.

Never mind the fact that there are no moose on Mt. Desert Island. This was Maine. Some people think that there's a moose on every corner, the moose is the state bird and the state flower, all rolled up into one. So I could forgive this woman if she thought I might be taking a picture of a moose.

Except for the small fact that I was pointing my lens DOWN at the water, not more than 20 feet below where we stood. Yes, moose do go in water. But if I was taking pictures of a moose, I'm almost sure that we'd both have been able to see it with our own eyes.

Trust me - there was no moose.

"No," I said, finally. "I'm not taking a picture of a moose."

She was not deterred.

"Oh, well," she said. "We'll find one I'm sure."

And with that, she raced back into her car and she and her companion zipped off on the loop road, in the direction of the Atlantic Ocean where, presumably, they came up empty in their search for moose.

Comments on NPN nature photography articles? Send them to the editor.

Kerry Leibowitz is a Midwest-based photographer with a particular propensity for the natural landscape. To see more of his work, visit his website at www.lightscapesphotography.com.