What is Fine Art Photography? Part 3 of 3 |

In part 1 and 2 of this 3 parts essay we looked first at the artistic aspects of fine art photography, and second at the technical aspects. In part 3 we are going to look at the marketing aspects.

C – Fine Art Photography: The Marketing Aspects

1 – Marketing considerations must come after the final image is completed.

The selling potential of an image should not be considered while the image is created. During each phase of the image creation the focus needs to be the expression of the artist's vision and his or her emotional response to the scene and the subject.

Inevitably, you will be asked if you considered the salability of specific images while you were creating them. And, if one of your images becomes a known best seller, part of your audience will be convinced that you created a best seller on purpose. Do not let that bother you. Keep in mind that not considering the selling potential of an image as you are creating it does not mean that this image will not be salable. Because the focus of fine art is upon the artist first and the work second, expressing your personality, vision, personal style, and emotions through your work is the best guarantee that your work will become financially successful.

In fact, focusing on marketing considerations alone can be detrimental to creating fine art photographs. This is because one of the main changes that a photographer needs to make in order to start creating fine art photographs is that of moving from selling images on the basis of the location or the subject featured, to selling photographs on the basis of the artist's name and personal style. Marketing considerations often involve focusing on specific locations or subjects because they are popular, but such an approach forfeits focusing on one's personal style. Doing so causes the artist to move away from the creation of fine art and to focus on the creation of commercially oriented art.

Although creating fine art photographs without focusing on subjects that rank high in salability might mean that your work will take longer to generate a profitable income, the outcome of this approach is the development of a personal style free from the influence of commercial considerations. What this means is that your style is developed on the basis of your vision and your personality rather than on the basis of what the buying public likes. This approach is far more likely to result in the creation of fine art pieces that reflect a true personal style. In turn, this style will allow you to command higher prices for your work than you would have been able to if your work had been commercially oriented.

2 – Fine art marketing focuses on a quality-based marketing model.

Fine art marketing needs to follow a quality-based marketing model. In a quality-based marketing model, business income is realized through the sale of a small number of high-priced items. This model is in opposition to a quantity-based marketing model in which business income is realized through volume sales of low-priced items.

This quality-based model is difficult to implement if you do not have extensive marketing knowledge. This is because sales are based on leverage and reputation rather than on price. For this reason many photographers follow a quantity-based marketing model because it is easier to implement, requires fewer marketing efforts, and is accessible to beginning photographers who have not yet gained leverage.

3 – Fine art is not priced on a cost-of-goods basis.

Fine Art is not priced on the basis of what it costs to make it. If it were, a Picasso would cost only a couple hundred dollars because paint, canvas, and stretcher bars are relatively inexpensive. A Monet, painted decades earlier, would cost even less, because prices for these supplies rose over the years between Monet's and Picasso's times.

Each year, as you file your taxes, you have to calculate your "cost of goods" for the IRS. The cost of goods is what it costs you, in supplies and materials, to create a specific piece. Your time is not included because it is not a tangible good; neither is your reputation because leverage is also not a tangible good.

After calculating your cost of goods, you know exactly how much each piece cost you to create. The first time I did this I was surprised at how low this figure was. I was also surprised at how much I was selling my work for in comparison to my cost of goods.

What I did not know then was that my marketing approach was correct. I was not multiplying the cost of goods by two, or four, or even ten. I was not taking the cost of goods into consideration at all when pricing my work. Instead, I was pricing my work based on how much time it took me to create it. Later, to this factor I added the leverage and reputation I had gained over the span of my career. In doing this no multiplying factor was applied.

4 – A fine artist charges for his or her time.

Your time is valuable. No matter who we are, rich or poor, famous or unknown, we all have 24 hours in a day and not a minute more. Since you cannot make more time, you have to charge for your time when it is used to serve somebody else's needs.

So you need to figure out how much you want to charge for your time. To do this, set an hourly rate and apply this rate to the number of hours you spend working on specific projects.

5 – A fine artist increases income by increasing prices, not by increasing output.

In the business of selling art, increasing your income is achieved by increasing your prices. As we saw earlier, you cannot increase your output without lowering quality or creating an "art factory." While creating a factory is certainly an option, and while a number of artists have done so successfully, it is not everyone's cup of tea (it certainly is not mine). So in order to increase your income without becoming a factory, you have to increase your prices.

6 - Art Movements and Personal Styles

As I mentioned in the introduction to this essay, artistic preferences are by nature personal. Different people will like or dislike different types of art, will prefer different artists, or will be attracted to different art movements.

It is therefore logical that not everyone agrees if a specific work of art is good or bad, or if it is art at all. Because art is such a personal endeavor, and because personal beliefs play such an important role in defining one's artistic approach, it is inevitable that not only critics but also artists themselves differ in their opinions regarding what art consists of.

This has been the case since the advent of art and this is what has brought about different art movements. An art movement is simply a group of artists who share similar beliefs regarding what they think art should be and who proceed to implement these beliefs in their art.

Throughout the history of art, movements have included cubism, impressionism, realism and modernism, among many others. Although all artists live in the same world and, arguably, experience the same reality, a cubist represents the world very differently than an impressionist. While the former represents the world as geometric shapes, the latter represents the world as the interplay of light and color.

Artists who belong to one movement rarely see eye to eye with artists who belong to a different movement. If they did they would all belong to the same movement. In fact, arguments between artists belonging to different art movements take place regularly, because these artists attempt to make their view of the world stand out as being more valid. As with most things in art, passion rather than reason drives these arguments.

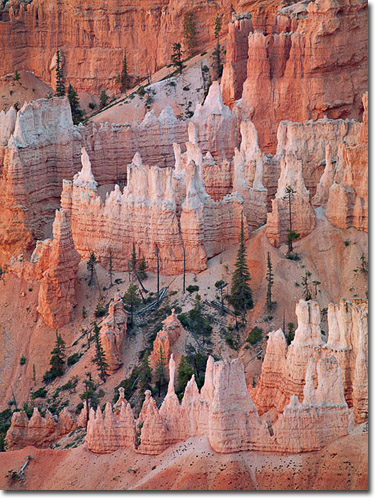

Bryce Canyon, Utah

As discussed above, personal style must be expressed visually in fine art photography. This is achieved through the use of various technical elements, such as composition, format, cropping, choices of palette(s), the use of curves and lines, etc. Taken individually, each of these elements represents a stepping-stone towards the definition of a personal style. Taken together, and provided that their use departs significantly from the approach followed by other groups of photographers, the combination of these elements can become the tenet for a new movement in fine art photography.

To complete this brief look at art movements it is important to point out the differences between an art movement and a personal style because the two can be easily confused. An art movement defines the specific direction, purpose, and vision followed by a group of artists. A personal style is the manner in which individual artists working within a specific art movement each create their personal work. In painting, personal style is often referred to as facture. A French term difficult to translate literally, facture refers to the "signature," metaphorically speaking, characteristic of a specific artist. By signature we refer to the way brushstrokes are laid out on the canvas, or the color palette favored by a specific artist, or the type of compositions, subject matter, choice of lighting—and a myriad of other details that characterize the work of this artist and that contribute to making it unique.

Many different personal styles can exist within the same artistic movement. In fact, when talking about accomplished artists who are members of the same movement, it is expected that each of them will have a different and unique personal style. Monet, Cezanne, and Degas were all members of the impressionist movement. However, each of them had a unique personal style. This means that a trained art enthusiast can easily identify a specific painting as being a Monet, a Cezanne, or a Degas by looking for the artistic elements that characterize their work. This is possible because while all three of them were working within the same movement, each developed a uniquely recognizable personal style.

In the paragraph above I used the term "trained art enthusiast." I could have said "viewer" instead. However, I wanted to be clear about what it takes to recognize the personal style of a specific artist. This is because it is easier for the beginning art enthusiast or "non-expert" to recognize an art movement than to recognize a personal style. For example, it is easier to recognize the differences between a cubist and an impressionist painting than it is to recognize the differences between the styles of Picasso and Braque, two artists who worked within the cubist movement. The same remark can be made about other artists who were members of the same movements.

It is worth noting that when an art enthusiast mentions that an artist has a specific style, they are often really talking about this artist being part of a specific movement. What they recognize are the characteristics of the movement rather than the specific approach that an artist uses to implement the tenets of the movement.

Similarly, when a casual observer mentions that an artist does not have a personal style, they often mean to say that this artist has not "invented" a new artistic movement. This comment is often heard in fine art landscape photography because few movements have emerged in this field. As a result, most fine art landscape photographers work within the same movement. Because of this, their work is fairly similar in its approach and the differences between the styles of particular fine art landscape photographers are difficult for a casual observer to identify.

7 - Handling Criticism as a Fine Art Photographer

A fine art photographer must be able to handle criticism well. Just as not everyone agrees on what is art, not everyone will agree that your photography is art. In other words, you will have fans and you will also have critics. You will have aficionados sold on your work and you will encounter those who see no value in it.

There are two important things to remember about this: First, this situation is inevitable. Not everyone will like what you do. Even if you create fine art landscape photographs, like I do, you will have people upset about what you do. They may be upset about the colors you use, the saturation levels in your work, the removal of certain elements by cloning, the warping of the photograph, the cropping, or any number of things that you probably would never have guessed would upset anyone, much less motivate them to take it up with you personally.

Such is the nature of art. Art creates passionate reactions and if your work creates such reactions it is proof that it is art. Most of the time these reactions are positive. However, occasionally they are negative and one must be able to know how to handle them and how to react. The best reaction is to listen and let it be. Do not take issue with it. Instead, simply point out that art is a matter of personal opinion and that the world would be a boring place if we all agreed on what is beautiful and artistic. After this is said, move on. If your interlocutor insists, I suggest that you politely let them know that they really need to spend their energy looking for art that they like rather than waste their time and yours.

Secondly, you must remember that it is those who are discontent, displeased or upset by what you do who are the most verbal. I have found that those who love what I do are far less expressive and tend to enjoy the work quietly and peacefully instead of manifesting their enjoyment in a loud public display of admiration. This situation may be a reflection of our society. It may indicate that we are far less expressive when we are happy than when we are unhappy. I don't know for sure. All I know is that this is a reality.

What matters is that you keep this in mind when you are confronted by someone who vehemently expresses their discontent with your work. Remember that unless your work is highly controversial, this person is part of a very small, although very verbal, minority. Also remember that you do not have to try and change this person's mind. In fact, even if you tried you could not do it. Their mind is made up and they do not want to be bothered by the facts. In fact, they would love nothing else more than to capture your attention and force you to spend your valuable time trying to make them happy. Don't do it. Instead, spend your energy helping those who love your work love it even more! Focus on the positive, not the negative. Focus your energy on those who love your work, not on those who dislike it and find issues with it. Give your time to your fans, not to your detractors.

8 - Counter-intuitiveness and Irony are Important Aspects of Fine Art Photography

There are some counterintuitive aspects in fine art photography. There is also some irony present when we compare what we do to what our goals actually are.

You may wonder why I am pointing this out in the context of a discussion about the nature of fine art photography. My motivation is simple: a large number of art enthusiasts, as well as a number of beginning photographers, are not familiar with this aspect of fine art photography. As such, they find it difficult to understand why we do what we do and why doing these things is important. As a result of this questioning, they fail to realize the importance of capitalizing upon the counterintuitive aspects of our art. They also fail to understand that this capitalizing is one of the essential aspects of fine art photography.

To clarify this aspect of our practice, and to help others understand it better, I've assembled the most common counter-intuitive aspects of fine art photography into a short list. Again, to emphasize the dual aspect I place upon fine art photography, I divided this list into two parts: technical and artistic.

Technical:

o Smaller f-stop numbers give you greater depth of field

o We see with two eyes but our cameras only has one eye (we must therefore recreate depth)

o Shade is more colorful than direct light

o Bad weather equals good photographs

o The best exposure rarely looks good without post-processing

Artistic:

o The light is more important than the subject (great subjects in bad light do not look good)

o We start to photograph sunrise before sunrise and finish photographing sunset after sunset

o We use a camera to take the photograph but we want to express ourselves

o Even though photography is highly technical, vision is more important than technique

o While it is the distant scenery that draws our attention, we need to pay close attention to the foreground if we include it in the photograph

I personally practice all of these things. Depending on where you are in your study of photography, you may already be doing some or all of these, or they may be new to you. Depending on your personal approach and style, you may agree or disagree with some or all of these things. This is perfectly fine.

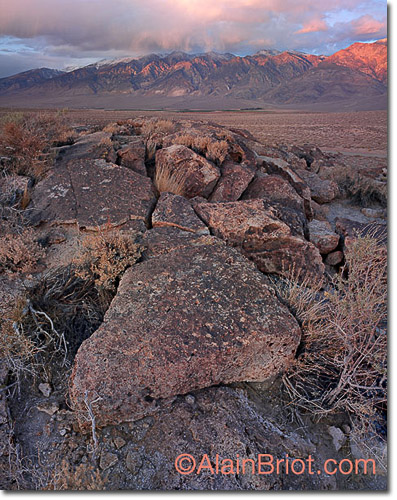

Volcanic Tablelands and White Mountains, Bishop, California

9 - What If You Cannot Do All of This?

Don't despair. I could not do what I describe in this essay when I began making photographs. I simply did not have the income or the knowledge required to do so. Most importantly, I needed to generate income right away. I did not have the luxury of learning and saving money until I had it all figured out.

What you can do, and what I did, is get started doing the best that you can even though it may be less than the full fine art requirements. Just keep your eye on the prize. The prize in this case is being able to create and sell fine art photographs. Why? Because doing so will raise your self-esteem (because you will be creating world-class pieces) and will also raise your net worth (because you will be able to obtain higher prices for your work).

10 - Terminology

It is important to note that fine art photography practitioners rarely refer to what they do as "fine art photography." They simply refer to it as "photography." This approach to terminology is typical of what I call "expert groups." Expert groups are groups of individuals brought together because of a specific interest and focus. These groups often refer to their particular use of the medium by the global name of the medium. I believe that this practice originates in the group's desire to present their specific use of the medium as the most important use, and to some extent, the only use to be considered seriously.

In this approach the global name of a medium is used to describe a specific use of this medium. The artist, who is essentially a specialist, sees himself as the one who defines what the medium is and what the medium can do. This may be due to art being used to push the envelope of the medium, to reveal new uses for the medium and to extend the boundaries of what can be done with the medium.

It is important to note that the use of this terminology is not limited to the artists themselves. It also extends to professionals working in the same field, such as gallery owners, critics, curators, etc., as well as to audience members who closely follow artists working in this medium, who go to openings and shows regularly, who read magazines focused on specific mediums and so on. The use of this terminology as well as of other terms commonly used in these relatively closed circles, permeates the language of all those who become part of these circles. Language becomes evidence that one is a member of these circles, that one is an insider or a participant at one level or another and not just an onlooker. Language and the use of the terms used in these circles are evidence that one belongs to these circles and is "in the know."

This is the case in photography when fine art photographers refer to their medium as being "photography," thereby ignoring the fact that photography has many other uses besides the creation of art. It is also the case in fine art painting when painters refer to their medium as "painting," and ignore the many other uses of painting besides the creation of art.

Similarly, it is the case in sculpture, dance, music, cinema and any other mediums when these mediums are being used for the purpose of creating art and when other uses of these mediums are ignored even though they are just as important and legitimate. Without going into an explanation about why that is, it is worth pointing out that it may be due to an elitist approach in which art is perceived by practitioners as being above all other uses of a specific medium making the artistic approach worthy of being named after the medium as a whole.

Sabrina Lake, Eastern Sierra Nevada, California

11 - Conclusion

A fine art photograph expresses the artist's vision and emotional response to the scene and the subject photographed. In this quest to express vision and emotions, fine art photography is first about the artist, second about the subject, and last about the technique.

It is not the technical quality of a fine art photograph that needs to stand out. It is its artistic content and the vision behind it. Ideally, mastery of both technique and vision must be demonstrated by the artist in his work. If the artist expresses his vision in a powerful manner and if the photograph is compelling enough, the audience is usually willing to excuse technical flaws. But if the photograph has no artistic content, technical flaws become impossible to ignore and the image is judged on technical aspects alone.

I recently visited Galen Rowell's gallery, Mountain Light Photography, in Bishop, California. What I found stunning during my visit was how grainy and relatively unsharp many of his photographs were. They did get better as films improved over the years, the most recent images being the sharpest and least grainy, but they were all pretty "rough." Yet, the power of the images was intact, this power being rooted in the artistic vision of the photographer rather than in the technical quality of the images.

The message expressed in the photographs, which to me is about experiencing the beauty and awesome power of nature through a physical relationship with the landscape, was in tune with the technique used to create these images. These are images created with 35mm cameras, most of the time handheld and often during extreme hiking or climbing conditions. It is therefore expected that the technical quality of these images could not be fully controlled and that sacrifices and compromises had to be made.

For Rowell, capturing the scene and the subject was more important than achieving impeccable technique. When looking at his work, one does not expect the resolution, clarity, and impeccable facture that a large format camera mounted on a sturdy tripod and loaded with high resolution and low speed film would deliver. Instead, one expects to see images of locations and events that are beautiful and uncommon. They are rarely photographed in ideal conditions because of the difficulty of doing so. In the end, what stays with the viewer is the experience of sharing the photographer's vision and adventures through his work. The technical aspects of the work, while being noticeable, do not hinder this experience in any way.

Comments on NPN landscape photography articles? Send them to the editor. NPN members may also log in and leave their comments below.

Alain Briot creates fine art photographs, teaches workshops and offers DVD tutorials on composition, conversion, optimization, printing and marketing photographs. Alain is also the author of Mastering Landscape Photography. Mastering Photographic Composition, Creativity and Personal Style and Marketing Fine Art Photography. All 3 books are available from Amazon and other bookstores as well from Alain’s website.

Alain Briot creates fine art photographs, teaches workshops and offers DVD tutorials on composition, conversion, optimization, printing and marketing photographs. Alain is also the author of Mastering Landscape Photography. Mastering Photographic Composition, Creativity and Personal Style and Marketing Fine Art Photography. All 3 books are available from Amazon and other bookstores as well from Alain’s website.

You can find more information about Alain's work, writings and tutorials as well as subscribe to Alain’s Free Monthly Newsletter on his website at http://www.beautiful-landscape.com To subscribe simply go to http://www.beautiful-landscape.com and click on the Subscribe link at the top of the page. You will have access to over 40 free essays by Alain, in PDF format, immediately after subscribing.

Alain welcomes your comments on this essay as well as on his other essays. You can reach Alain directly by emailing him at alain@beautiful-landscape.com.