Imposing Your Artistic Vision |

Two Zen Buddhist monks were arguing about a flag. One said: "The flag is moving." The other said: "The wind is moving." A Zen master happened to be passing by and overheard the conversation. He told them: "Not the wind, not the flag; mind is moving.” - Famous Zen Buddhist Parable

I’ve read a fair number of Zen parables, having gone through a comparative religion phase many years ago. While most are cryptic, even undecipherable, I think I get this one: it is saying that the mind is a very powerful component of perception, and that our minds create, to some extent, “reality.” Now, I don’t believe this to be completely true: deny the existence of the flag or the wind all you want, it won’t make either of them go away. I do believe, however, that photographers have the ability to go beyond the flag and the wind, and to change the reality of a subject. All we have to do is to get our minds moving.

"Superior Dawn" A thirty-second exposure blurs moving clouds and waves for an impressionistic effect. Or was it my mind moving? Lake Superior, Tettegouche State Park, Minnesota

But how does one train their proverbial “inner eye” on a subject? The key is to learn the art of abstraction. Abstraction is the ability to see a subject in a non-literal way. Here’s an example: most people, when they see a mountain, see . . . well, a mountain. The abstract thinker sees something else: a triangle shape. Same with rocks, trees, and streams: they become rectangles, vertical lines, and curves, as well as alternating tones of color, light and shadow. Learning how to see elements of a scene as abstract shapes and tones, and learning how to arrange those shapes and tones in a pleasing way, is the key to improving your photography, and will help you transform your images into something more than mere pretty scenery. The ability to “see beyond” a subject’s outer appearance, and to instead portray the subject in a surprising or unique way, is critical to creating art that will have an impact on the viewer.

"Stinging Sands" I didn't see sand dunes, instead I saw repeating curving shapes and alternating tones of shadow and light. Great Sand Dunes National Park, Colorado.

Once you learn how to think abstractly, you can impose your artistic vision on a scene, rather than having the scene impose itself on you. What this means is that you will start making affirmative creative choices, rather than just taking snap-shots of pretty scenery. Taking control of the creative process, and not just leaving it all up to Mother Nature, is a critical component of artistic expression. Don’t wait for the flag or the wind to move, get your mind moving and the rest will follow.

Thinking abstractly can improve your photography in several ways. First, even if you don’t intend to create abstract images, the ability to think abstractly allows you to consider and create images and compositions that might not occur to a literal photographer. Second—and this almost goes without saying—abstract thinking is a necessary component of creating successful abstract images.

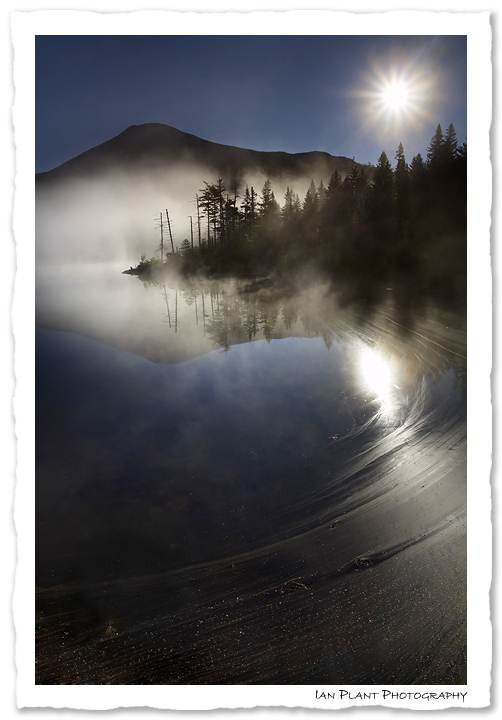

Let’s move from inchoate principles to concrete examples. In the image below, I had a wonderful scene emerging out of the morning fog, with the sun rising over distant mountains, backlighting the mist coming off the lake. I experimented with several shots, but nothing seemed to work until I noticed the sweeping curve of the “scum line” in the water. Only by thinking of the “scum line” abstractly—viewing it not as nasty residue on the water, but rather as a beautiful sweeping curve leading the eye from foreground to background—was I able to take this scene to its fullest potential.

"Morning Star" Scum is in the eye of the beholder! Lake Colden, Adirondack High Peaks Wilderness, New York

Take also this next example of a waterfall in northern Maine. I made several images of these falls, but was not really happy with any of the results. The reason, I discovered, was that I was thinking too literally about the images I was making, trying to create an image of the falls, rather than seeing the falls as an abstract element of the scene. Once I started thinking of the falls as an abstract shape and creating compositions that related that shape to other shapes in the scene, I was able to create a more successful image. To me, this scene is all about the repetition of the curving shape of the tree throughout the image.

"Screw Auger Falls" An unfortunate name for a beautiful waterfall, brought to its fullest potential when I thought abstractly about the elements of the scene. Gulf Hagas Preserve, Maine.

Abstract thinking can also help with wildlife photography. For the image of the great egret below, I decided to move beyond a mere literal interpretation of the subject. Instead of trying to create a shot that showed an egret, I choose to create an image that was more “representational” in nature. I choose a camera angle and lighting that would render the egret in silhouette, and used the dark reflection of shadowed trees to frame the egret. Then, it was all a matter of waiting for the right moment, repositioning my camera as necessary as the egret moved around, finally getting this abstract shot when the egret struck its prey.

"Egret Dawn" An abstract, "artistic" rendering of the egret was more satisfying to me than a traditional tight portrait. Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, Virginia.

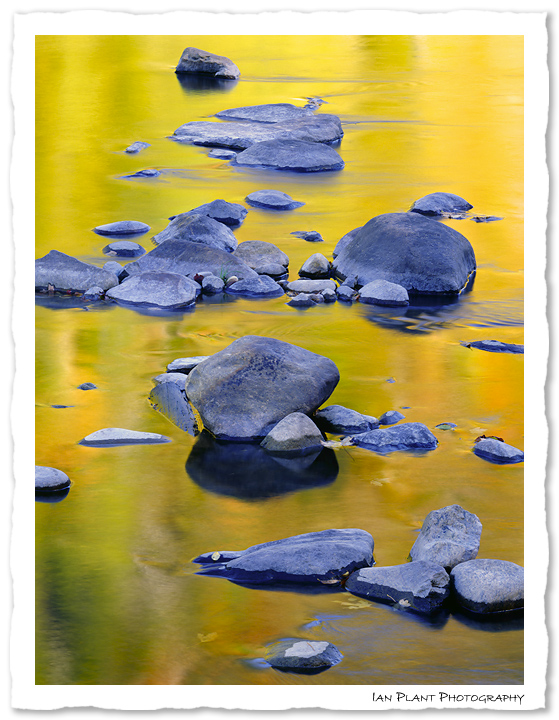

Learning to see abstract shapes is important, and equally important is learning to see images in terms of color and tone. The image below is driven by the contrast between the cool tones of the shadowed boulders, and the warm tones of the reflection of sunlit autumn foliage in the water. The shapes formed by the interaction of contrasting colors create a pleasing abstract image.

"Sermons in Stones" Color contrast can be used to powerful compositional effect. Ausable River, Adirondack State Park, New York.

Abstract thinking can also help you create images that are representative of transitions in nature or movement over time. I created the next image, of fog moving over mountains, by using neutral density filters to achieve a twenty-five second exposure. The result is an abstract study of movement over time, which captures more accurately a sense of the moment than would have been possible with a short exposure.

"Earth Shadow" Although cameras are designed to capture a single "moment," by using long exposures you can create abstract images that show motion over time in a way that still or video captures cannot. Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee/North Carolina.

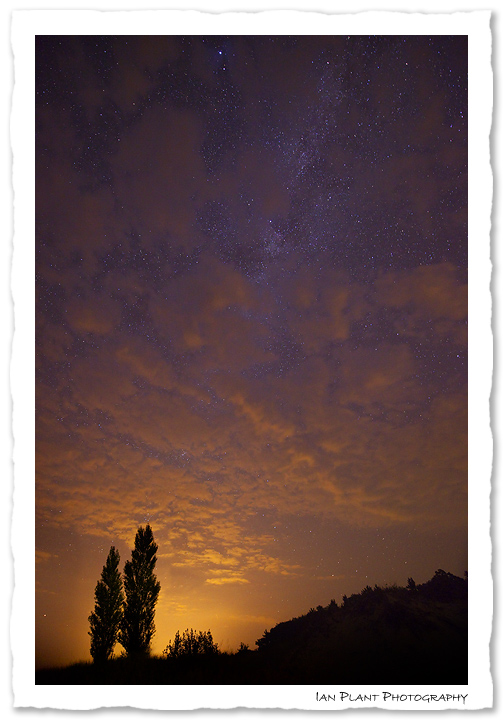

The final image below is a single image of clouds passing below the Milky Way at night. Distant city lights illuminate the clouds and the horizon with a warm glow, which contrasts with the cooler tones of the heavens above, creating an illusion of transition from sunset to night. By thinking abstractly, and by taking advantage of the color contrasts and shapes in the scene, I was able to create an image that presents a scene in an unconventional way.

"Twilight Transition" Creative use of color contrast creates an image that looks more like a combination of multiple exposures for artistic effect, rather than the single image that it really is. Lake Michigan, Nordhouse Dunes Wilderness, Michigan.

Learning how to think abstractly may seem as difficult as achieving a state of Nirvana, but it is critical to improving your artistic vision, and imposing that vision on the natural world around you. So get your mind moving!

Comments on NPN nature photography articles? Send them to the editor. NPN members may also log in and leave their comments below.

NPN Contributing Editor Ian Plant is a full-time professional nature photographer, writer, and instructor. His images and instructional articles have appeared in a number of books, calendars, and magazines including Outdoor Photographer, Popular Photography, National Parks, Blue Ridge Country, Adirondack Life, Wonderful West Virginia, and Chesapeake Life, among others. Ian is the author/photographer of eight books, including the critically acclaimed Chesapeake: Bay of Light. Most recently, Ian was one of the lead authors and executive editors for The Ultimate Guide to Digital Nature Photography, and co-author of 50 Amazing Things You Must See and Do in the Greater D.C. Area. Ian is co-owner of Mountain Trail Press and Mountain Trail Photo, and he leads several photography workshops every year.

To see more of Ian's work, visit Ian Plant Photography and Mountain Trail Photo. The Mountain Trail Photo Team consists of some of the top nature photographers in the country, whose mission is to educate and inspire others in the art of nature photography. There you will find team member images; articles on photo techniques and destinations; and information on workshops in some of America's most beautiful places. Also visit the Team’s Blog for a more eclectic mix of images and musings.