My ideal is to achieve the ability to produce numberless prints from each negative, prints all significantly alive, yet indistinguishably alike, and to be able to circulate them at a price not higher than that of a popular magazine, or even a daily paper. To gain that ability there has been no choice but to follow the road I have chosen. - Alfred Stieglitz

Introduction

This essay stems from my ongoing reflection on the subject of limited edition prints. "To limit or not to limit, that is the question," is how I start the essay. How I end it is to be found by reading this essay.

This essay also comes out of what I see as the increasing importance of the limited edition debate, for lack of a better term (there's really no specific name for this debate which is mostly informal, though important, at this time).

The clincher for me was the realization that at a time of constant technical improvements, limiting and consequently discontinuing new printings of an image (and by implication discontinuing landmark images eventually) was preventing the creation of better and better prints of this image.

There is a lot of thought being given today to the issue of numbering prints. Photographers who decide to sell their work ponder endlessly whether or not to release their prints in limited editions. This question worries many photographers today.

It is worth mentioning that photographers who do not try to sell their work suffer no such quandary. They simply print their work, wasting no time on how many prints of a single image they make. Instead, they concern themselves with print quality rather than with print quantity.

Truth be told (extend your hands in front of you, palms facing each other, as you say this), numbering photographs is a marketing game. It serves no purpose with regard to the quality of the print. Instead, it is used to artificially increase the perceived value of a particular image while the photographer is alive.

The marketing principle goes like this: reducing the quantity by a measurable amount will allow the photographer to increase the perceived value, and in turn, the selling price by a commensurate amount. In other words, the smaller the edition, the higher the price of each print in this edition. An edition of 10 will allow each print to be priced higher than an edition of 100, which in turn will be priced higher than an edition of 1000 and so on. The respective price of each print is set by the photographer, the gallery, or both. Pricing is no small task, and is often just as challenging as setting the number of an edition. However, pricing is a very different issue that I will not debate here.

The whole question then becomes “how big (or small, as you prefer to put it), should a given edition be?” The answer, for the most part, lies in the photographer’s expectations for upcoming sales. In other words, how many prints of a given image can a specific photographer expect to sell? 10? 100? 1000? More? “Smart” marketing dictates that you need to find that number and set the edition at this number or slightly above, just in case you were pessimistic. You noticed I said “smart” marketing. I did so because it may, after consideration, not be so smart, an issue that I will come back to later in this essay.

Manipulation And Art

Sounds manipulative, doesn’t it? If it does, that’s because it is. To prove it, let’s back off a little. Why do we collect, or purchase as the case might be, fine art photographs? Is it because they have a number on them (Ansel Adams prints don’t have numbers)? Is it because we expect them to increase in value (many prints do not increase in value)? Or is it because we love the image? Truth be told (extend your hands forward again, palms facing), most people collect or purchase images because they love them. And while the investment value might be a concern, few if any (at least collectors who intend to display their prints and not keep them in dark storage) purchase a photograph solely because it is limited in number.

This is not to say that the numbering approach does not generate extra sales. It does. This is simply to say that loving the image and enjoying the work of specific artists are the reasons why collectors purchase prints. Numbering comes later in the selection process, after one has decided that they love a specific photograph enough to purchase it. My belief is that once someone has decided to acquire a specific photograph, the presence (or absence as we will see shortly) of numbering is the “clincher,” i.e. the final element that closes the sale.

A Short, Short History Of Numbering In Photography

The fact is that numbering is a fairly recent development. Some of the photographs that have become most valuable today were not numbered. They are limited in number simply because the photographers stopped printing them, usually because they are deceased. Most of the biggest names in photography, such as Ansel Adams, Edward Weston and so on, did not number their prints and only limited the edition number of portfolios. Adams actually said (I paraphrase), "Why limit the number of prints one can make from a medium that is, by nature, unlimited and in which each print of an image is potentially as good as all other prints?"

Alfred Stieglitz, who owned Gallery 291 in New York City and was influential in introducing photographers and artists to the American public, offering Ansel Adams his first show in New York City said, “My ideal is to achieve the ability to produce numberless prints from each negative, prints all significantly alive, yet indistinguishably alike, and to be able to circulate them at a price not higher than that of a popular magazine, or even a daily paper. To gain that ability there has been no choice but to follow the road I have chosen.”

This quote needs some explaining, I believe. For one, Stieglitz does endorse the no numbering approach in this following (or influencing, as it may have been) Adams’ position. Both believed that photography should be left to do what it does well, and that is produce limitless numbers of prints each of the same quality. The outcome was the possibility to offer large amounts of prints for a low price per print.

Certainly, this approach means quantity sales while retaining quality of printing at the same time. I personally find this endeavor very challenging. Of course, it all depends on what quantity we are talking about. In the case of Stieglitz, the quantity of prints of any given image is relatively small, so small in fact that by today’s standards these numbers wouldn’t be considered quantity. Therefore, I believe that Stieglitz did endorse quality while refusing to number his prints. Adams followed the same approach. Even though Adams’ prints were not numbered, his most popular images hardly exceed a quantity of 1000 prints total. Whether that is quantity or not depends on how you feel about this number, but we are talking here about a world-known artist printing his most famous images. I am sure we can all find examples of far larger “editions” of lesser-known images.

As I explained earlier, I believe that numbering is done for marketing purposes, to artificially increase the value of a print while the photographer is still alive. Why while he is still alive? Because after he has passed away, the edition is by nature limited to the number of prints made by the photographer during his lifetime.

But things do not stop there. I own an 8”x10” Edward Weston print, which I purchased because I love it, printed by his son Cole. This print, just like the prints made by Edward himself, is not numbered. In fact, I doubt that any print from a negative made by Edward Weston, has ever been numbered. The value of this print, at the time I purchased it, was $3000 while prints made by Edward himself were at least twice that for even the least expensive and many times more for the most expensive.

These are respectable prices for 8x10 prints. They show that print value is not only, or not so much, controlled by numbering and artificial control of the number of prints made from a given image. In this instance, the value of a non-limited print done by the son of the photographer remained quite high despite the fact it was not printed by the original artist and was not numbered or limited in any way.

Why is it so? It’s because of the power of the image, the extraordinary quality of the print, the name of the photographer, and the recognition bequest upon him by the photographic and artistic community. That alone, to me and to many collectors, is enough to justify making a purchase. We do not need a number in the lower left hand corner of the print, or on the back as the case might be, to further motivate us to purchase the image. In other words, who cares how many prints were made when they are as stunning and beautiful as this one.

The fact is that we know, maybe not explicitly but certainly implicitly, that photographic artists make relatively few fine art prints of individual images. Why? Because this is fine art photography and artists have a difficult time selling their work. The art market is a rarefied one where most artists sell just a few prints of any given image. Even the “biggest” names out there make less than a thousand prints of their most famous images in their lifetime. Only a few exceed this number.

Art will be art, a field in which high numbers are not only uncommon but also most often unheard of. Those who believe that they have to have a number on their print so that they have evidence that the artist won’t be printing “tens of thousands of copies” of a given image are not only uneducated in the nature of the art world, they are also delusional. Tens of thousands? I wish. It would be a very different business then. In fact, for many photographers, it may actually become a business!

At certain art shows, such as the one above in Scottsdale, Arizona, artists must offer limited editions in order to be invited to the show.

However, when sales are brisk, the number of different photographs for sale high and the editions relatively large, one can reasonably wonder whether these limited editions offer added value to the audience or not.

Are the limited editions a guarantee of quality (or even quantity) or are the artists doing what is asked of them in order to join a potentially lucrative selling venue?

Of Quality And Quantity

The issue of quality versus quantity is central both to my own work and to my teaching. I practice what I teach and teach what I practice. I see no other way, not being prone to double standards. Life is just too short and having two different ways of doing any given thing is just too complicated. Plus, it's unethical and shows a lack of integrity. My first encounter with quantity took place when I started selling my work. My goal, little did I know, was to sell a print to everyone on the face of the earth. I know this sounds silly, or delusional, but such was the case. The fact that I sold my work at the Grand Canyon, a location known worldwide and the destination of five million international visitors each year, actually made this goal not so delusional. Regardless of the accuracy of my thinking, the fact is that I was well on my way to doing so when the workload nearly killed me. Did I make 1000 copies of any given prints? I may very well have. Fact is, I didn’t count. My goal was to “crank out” as many prints as I could in the shortest amount of time, something that was a real challenge, as I could not keep up with the demand.

I realized my error early enough to correct the course of my career and point my metaphorical boat in the proper direction. I realized that aiming for quantity was an exercise in frustration, one that would destroy my health and greatly reduce the value of my work. Most importantly, I realized that I could not generate both quality and quantity. At least not without hiring employees and designing a system in which others were responsible for many of the less critically creative tasks, something that I was not willing to do.

As a result, I became a proponent of quality work rather than quantity work. This means that no shortcuts are taken during any phase of the creation of the image, from conception, to capture, to processing, curating, matting, etc. The goal is not to save money or time in the process. Instead, the goal is to use the finest tools and supplies and take all the time necessary to create the finest quality artwork possible, bar none.

By nature, this means reducing the number of prints. Because each print takes longer to make, there will be less prints made. Because more time is spent creating each print and more expensive equipment and supplies are used, the price of each print will be set higher and fewer people will be able to afford them. In marketing terms, in a quality-based model, the income is made from a few sales for a high price per sale. This marketing model is by nature limited and does not need to feature limited editions to work. It is used widely in the fashion designer industry for example. While I believe it might exist, I have never seen a limited edition dresses, purses, shoes or other.

Quality instead of quantity also dictates that the artist continuously seeks to create new images that further his vision. Therefore, instead of spending all his time in the studio, the artist needs to divide his time between fieldwork and studio work, between the printing of previous images and the creation of new images. Upon return to his studio, the artist needs to work on his new images. This approach forces a reduction in the number of prints made from any given image since the artist is placing his efforts as much on new prints and on previous prints. In fact, as is often the case, artists place more emphasis on newer work, focusing on printing their latest images rather than their previous images, an approach that further reduces the number of prints made from any given image.

This process, by its very nature, automatically reduces the number of prints made from any given image. Why further complicate things by numbering each image? Isn’t this enough to guarantee that collectors will have collectible pieces? Here too we can see how numbering is a marketing decision rather than an artistic decision. Nothing wrong here, mind you. Marketing is still legal in the United States. However, and since we are talking business and not art, the question begs to be asked: does it work? More specifically: does numbering limited edition photographs result in more income for the photographer?

There is nothing that says it cannot work or that a higher income can be achieved. On the other hand there is nothing, per se, that says it is the only marketing model by which photographers can receive higher prices for their work. In a quality versus quantity marketing approach, in which both seeking the finest quality (as I do) and numbering prints (as I don’t do) are used, commanding higher than average prices for your work is important. It is important because you since you cannot realize your profit margins on a large number of sales you must realize this margin on just a few sales.

The Problem

The problem is that the limited edition approach in photography was defined at a time when chemical photography had reached its apex and before digital photography was introduced. At that time, which we could define as being, broadly speaking, from the late 70’s to the early 90’s, the limited edition marketing model worked great. In fact, it worked better and better as chemical photography became more and more mainstream, better known, and practiced by a larger and larger number of photographers. Why? Because the more photographers are out there competing to sell their work, the more the buying audience wants justification for the work. And numbering is that: a justification for the price and the quality of the work.

The argument goes like this: if it is limited, it must be good. And if it is good, it must be expensive. And if it is expensive, it needs to be limited. And if it is limited, it is good… It is a circular argument, but circular arguments work, unfortunately.

The problem changed when digital was introduced. While chemical photography was stable, with few major changes taking place in regards to quality improvements, digital was (and still is) in a state of constant change at every technical level. Print permanence, color gamut, contrast control, paper choices, dynamic range, bit depth and just about every other fundamental technical aspect of digital photography has changed dramatically since digital photography became a reality for photographers. Simply comparing a print made in the mid 90’s to a print made today will prove this point. Even comparing a print made in the early 21st century, say 2002, to a print made today, in 2008, will prove the point. In fact, comparing a print made last year to a print made this year may even prove this point. It all depends how closely you want to look at the differences between prints.

Art collectors, and particularly fine art print collectors, look at the differences between prints very closely. They are very meticulous in their study of a print. Most of them can recognize fine variations of tone and color that would elude more casual observers. Some of them carry a loupe. They know what makes a good print, and they search for the finest prints. They look for prints that they can fall in love with because of the variations of color and tonality that are captured in the print, and because of the emotion that they feel when they look at the image.

Thanks to digital photography, bringing these fine variations of tone and color, and bringing to life the emotional content of a print, is becoming something that photographers have more and more control over. Why? Because the technology, the tools, and the supplies are constantly being refined. The medium of digital photography is getting better and better everyday.

However, there is no guarantee that a given painter will not paint the same subject, or the same composition, over and over again. Magritte is famous for doing so. He made no secret that he filled order after order of his most popular paintings. Each was an original, but each was also similar to the previous renditions of the same image. The brushstrokes may not have been the same, but the images were.

Painters do not face the same problems as photographers when it comes to guaranteeing the originality of their work. Each and every painting is an original. This can be easily verified by looking at the paint on the canvas. No possible mistake there.

This brings up the question of where the original quality of a piece begins and ends? Does this originality reside in the medium or with the vision of the artist? Clearly, any piece can be reproduced time and over again, regardless of the medium. Certainly, a photograph is easier to reproduce than a painting since the photographic reproduction process can be automated while a painting requires manual work. However, the possibility is there, even though it may entail more effort

The Conflict

Such is the case, and only fools would contest it. Evidence is all around us and it is a universally accepted fact. Still, in this situation, some artists who release a print today, and who hope for their image (as they should) to sell out quickly, do so in limited editions by setting a specific number for each image. How, in this situation, and provided that the print sells out (which is the goal after all) will these artists be able to take advantage of the constant improvements made to digital photography by printing a better version of their image in say, a year’s time? Truth be told (extend your hands), they will not be able to offer a better print of this image because their edition is sold out and they have promised not to make any more prints of this image.

Problem then conflict. Problem because the goal is to do quality not quantity. While the quantity may be there through the numbered edition approach, the quality won’t be there very long because of the constant improvements in digital technology.

Conflict because while these artists want to guarantee the finest quality to their customers, they actually make it impossible to continue offering this finest quality since they have to stop printing an image, not because they cannot print it any better, but because they came to the end of the edition. This has nothing to do with art. At this point marketing has taken over and art has been pushed aside.

Of course, every problem has a solution. Unfortunately, some of the solutions to this problem are not very elegant. One can, and many in fact do, release the same image in a different size, thereby allowing themselves to start a new limited edition. The “edition by size” approach is widely used. Artists don’t feel all that good about it and clients are suspicious of its validity. If an image is offered in, say, 5 different sizes, from 11x14 to 40x50, and if each size is offered in a limited edition of 100, is this edition still truly limited? And if a new size is created, say 18x24 instead of 16x20, because the 16x20 size has sold out, is this an honest practice or is it just a way to continue offering a best selling photograph in a limited quantity? Finally, what if the 18x24 size sells out? Do you invent a new size and continue playing this game?

Good question. My answer? Just say no to limited editions. It will make your life simpler and you won’t have to deal with questions that challenge your integrity. And above all, if you do digital photography, like I do and like most photographers do today, you really don’t have another choice unless you sell a print every couple of years in which case you should either re-evaluate your marketing skills or stop selling your work.

Why is that? Because by limiting an edition one implicitly says that this is the finest print that can be made from this image and that this image cannot be printed any better later on. That position was fine with chemical photography because from 1980 forward the medium was relatively static, improvement wise. However with digital photography, the medium is far from being static. Instead, it is in a state of constant change and significant improvements to the technology take place on an ongoing basis.

These improvements directly inform the issue of quality because they allow us to make better and better prints. Therefore, in this situation, it is fair to question why someone would limit the quantity of prints made from a specific image. What if you sell out the edition of this image and then find out, in a year or so (as you most likely will) that you could print it better than you ever did before? If you number and the edition is sold out, you are out of luck! You can't print this image anymore without breaking the promise you made to the collectors who purchased your work.

Certainly, you could argue that by setting a relatively high number of prints in the edition, larger than you can reasonably expect to sell, you keep open the possibility of improving the print quality as the technology improves while not selling out the edition. The problem I have with this approach is that it is marketing based on planned failure, not planned success. I believe it is much better to plan on being successful and to act accordingly.

The other problem with the planned failure approach is that limited editions are expected to sell out. That is the nature of limited editions. Limited editions generate interest because of the rarity of the work, therefore they need to sell out for the marketing model to work. If you offer limited editions and none of them are sold out, the purpose is defeated. What do you think of artists who offer limited edition prints that are constantly available and whose editions never sell out? If you are like me, you don’t think very highly of them. Do you want to be one of them? Personally, I wouldn’t want to.

The Art Show Conundrum

An interesting aspect of this conflict is presented by art shows that require artists to offer limited edition prints in order to be included in the show. This does not include all the shows offered in the US, or in the world, but it does address a significant number of them. Most importantly, the shows that require artists to offer limited editions are usually high-end shows, meaning they have a higher level of reputation and “clout.”

The logic behind the requirement that all prints be released in limited editions in order to be sold at specific shows stems from the desire to prove to the audience that the artists in the show do not print limitless numbers of the same images. While this goal is certainly commendable, it does force artists who desire to enter these shows to number their prints since this is a sine qua non condition for being invited to these shows. Number and you will be considered for acceptance in the show. Do not number and you are automatically rejected, regardless of the actual quality and artistic value of your work, and regardless of your personal career path and achievements.

In other words, these shows have built a door through which artists must pass in order to be invited to display and sell their work. This door can only be opened with one key: offering limited edition prints. If you do not offer limited edition prints you will never pass through this door. This basically means that artists who take the position I offer in this essay cannot participate in these shows unless we decide to sell only portfolios, an approach that is certainly possible.

What are you to do if you desire selling at such shows? There is only one approach possible: number your prints. Just keep in mind this is purely a marketing decision, a decision you must take in order to sell your work at these shows. In other words, in order to reach the audience that these shows cater to, you must number your prints. Numbering then becomes the key to accessing this audience, the key to walk through the metaphorical door I described earlier and market your work to the audience addressed by these shows. In other words, while this is an issue specific to certain shows, here too numbering is purely a marketing decision.

What Are You To Do?

Provided all this, what are you to do? My recommendation is to make a decision based on your beliefs on this subject as well as on your personal situation. If you want to participate in art shows that require artists to offer limited editions, the decision is to offer limited editions. If you sell so many prints that you want to limit how many copies of one image you print, again the choice may also be to offer limited editions.

This, in fact, is the position adopted by a number of contemporary artists such as Rodney Lough or Michael Kenna. They release their images in limited editions citing their desire to not spend the rest of their lives printing the same image over and over again and again as their motivation. This is certainly a valid reason to limit the size of an edition. The problem? It really only applies to a very small number of artists. Most photographers have the exact opposite problem, which is that they would love to print more copies of the same image but cannot find enough collectors to purchase their work.

Another possible approach is the “pricing based on sales” approach. Under this marketing model the price of a specific image goes up progressively as the image becomes more and more popular. If a piece becomes very popular, it ends up becoming very pricey. It is then up to the buying audience to decide if they are willing to pay the premium for a specific piece or if they would rather purchase a piece that is less popular but more reasonably priced. Under this model the edition size sort of takes care of itself since as the prices go up sales are expected to go down proportionally. Christopher Burkett uses this pricing approach for example. Often, images sold under this approach will be divided in tiers, such as Tier 1, 2, 3, etc. Images are moved from one tier to the next according to how well they sell. The price of each image increases as they move from the lower to the higher tiers.

It may help to know that not all well-known and successful photographers, dead or alive, have or currently offer limited editions. In fact, many of them don’t. I mentioned Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, certainly two of the most famous names in landscape photography. However, other landscape photographers, such as Charlie Cramer or Michael Reichmann, do not offer limited editions either. To help find out where you stand on this issue, I recommend that you compile your own list of photographers who do or don’t release their photographs in limited editions. I also recommend that you include your favorite photographers in this list, as it will be more meaningful to you that way.

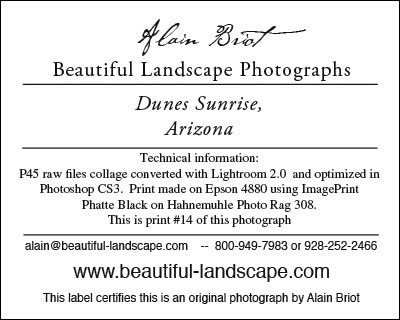

What I also recommend, keeping in tune with the ever-changing nature of the digital photography medium, is that you affix to the back of your prints a label stating, as is traditionally done, the title of the photograph and your personal information. I also recommend that this label detail the relevant printing data for each specific image. This data can include the following: the printer brand, type and inkset used, the paper manufacturer and type, any finishes applied to the print such as protective coatings, the type of profile or the rip + profile used, the version of Photoshop, or other imaging software used to prepare the master files, etc.

This list can be expanded and customized to fit your needs so as to include any and all information that you find relevant. What is important is that it does provide information about the materials, the hardware and the software used to make the print as well as the date the print was done. Certain artists also include the print number, that is how many prints of this image were made at the time a specific print was done. This information is usually provided by saying that this print is number 17 (for example) of this particular photograph.

This approach is different from releasing a limited edition because no limit is placed upon how many prints of a given image will be made. However, it does provide information about how many prints of a given image are out there. I also suggest that you make the total number of prints available to customers who request this information after making a purchase since this numbering approach only informs the buyer about how many prints of a specific image exist at the time their order was placed. It does not provide information about the number of prints released afterwards.

Finally, if you do release a limited edition, for example of a portfolio, keep the number of pieces reasonable. This number will vary from one photographer to another, but small numbers are preferable in my view. Personally, I think that editions of 50 are a good number for editions of prints 16x20 matted size or so, and that smaller editions, of 25 or less for example, are preferable for larger pieces such as 20x30 and larger matted size. Creating very large editions that may never sell out casts doubt on the validity of limited photographic editions as a whole.

My current print label, which is affixed to each print sold, either on the mat backing board when the photograph is sold matted, or on both the backing board and the back of the frame when the photograph is sold framed. The technical information is typed individually for each photograph and changed as needed to reflect the exact technical information about each print.

Conclusion

I believe that, first, numbering comes out of a static approach to photography, an approach in which the artist believes that he has made the best possible print from a specific image and will never be able to do any better. This no longer holds true today in a world where technical advances are made if not daily or weekly then monthly and definitely yearly.

Second, I believe that numbering also results from an approach in which realizing a desired income today is more important than achieving the finest print quality tomorrow. While more somber in nature than the first reason, this is unfortunately also the case. Eventually, the artist's integrity and in turn the artist's income, suffer.

When I realized all of this about 2 years ago, I decided to stop numbering my prints. I now only number my portfolios, the way Adams did, because they are collections of prints and not single images. Portfolios represent a body of work that was completed at a specific date and time. Certainly, the quality of the prints in the portfolio can be improved as the technology changes. However, so far I have not re-released a portfolio in order to offer a new print quality and I have no plan of doing so. The portfolios remain the same, each of them a testimony, if you will, to the print quality that could be achieved at a particular date and time. The prints from portfolio images that are sold as single prints do, however, benefit from the latest advances in printing and are continuously improved. These are not numbered. All prints, either in portfolios or not, come with a label similar to the one above.

I do number images that are limited by nature. For example, photographs that were painted upon or to which something was added after the print was completed, either with pencil, paint, gel, etc. These may be referred to as mixed media, although I am not so fond of this name. I prefer to refer to them as pieces that were completed with non-photographic means. I do very few of these at the time I am writing this essay, but this may change in the future. These are usually 1 of 1 and indicated as such. They fall between paintings and photographs in this respect. I expect we will be seeing more and more of this type of work in the near future. Kim Weston, for example, is currently working on images that fall in this category. It may bring an interesting twist to the numbering issue as well as some interesting questions. If a photograph is unique, is there still a reason to number it? Is there a need to limit what is already limited or to make obviously unique what is already unique?

The renaissance of alternative printing processes also offers an opportunity to create work that is by nature limited. Platinum palladium printing, for example, is a meticulous, lengthy and expensive printing process. The resulting prints are beautiful, but the nature of the platinum palladium process means that these prints are by nature limited in quantity. Why? Because this process cannot be automated the way inkjet printing can be automated. It is, by nature, designed to yield one print at a time. Furthermore, each print will come out slightly different from the next, even when printed from the same negative.

What I am saying here is that there are approaches that allow photographers to create unique work without having recourse to limited editions. These approaches, such as combining photography and painting or using alternate printing processes for example, will by nature result in a limited quantity of work because they cannot be automated.

Eventually, how you approach this issue is a matter of personal choice. As they say, this is a free country and I believe it is. In fact, this belief defines much of my thinking and my approach to photography. However, at this time in history, it does appear that besides marketing there are few if any compelling reasons to limit how many prints of a given image you can make. To limit an edition is to prevent yourself from printing a specific image better later on, or to give yourself undue headaches, or both. I see no reason to take this route when collectors make purchasing decisions based on how much they like the image and when digital technology is developing so quickly as to virtually guarantee us the capability of creating better prints tomorrow.

Comments on NPN digital nature photography articles? Send them to the editor.

Alain Briot creates fine art photographs, teaches workshops and offers DVD tutorials on composition, printing and on marketing photographs. Alain is also the author of Mastering Landscape Photography. This book is available from Amazon and other bookstores as well as directly from Alain. You can find more information about Alain's work, writings and tutorials on his website at http://www.beautiful-landscape.com.