|

Each fall, several thousand Lesser Sandhill Cranes stage at Creamerís Field Migratory Wildlife Refuge as a part of their fall migration. The Refuge, a former dairy, is managed by the Alaska Department of Fish & Game as a working farm and hosts large numbers of waterfowl in both the spring and fall. But itís in the fall that the Sandhill Cranes arrive in impressive numbers.

The Refuge is located in Fairbanks, Alaska on the northern edge of the town. While the fractious Alaska residents donít agree on many environmental issues, the range of beliefs and people that make a point to visit the cranes each fall gives even the most disenchanted environmentalist some hope for common ground. NRA and Audubon bumper stickers are on adjoining cars, and their respective drivers watch and listen to the birds with the same evident delight. Parents bring children, and sometimes you can see the connection between man and nature, between human time and natural time, freshly remade.

The cranes are also the stars of the annual Tanana Valley Sandhill Crane Festival, usually held in the third week of August. Sponsored by the Friends of Creamerís Field, the Festival also features a special guest, usually a scientist, artist, writer or photographer whose work has focused on cranes and their worlds. Some of the seminars are held outdoors. And sometimes the speakers have to pause while an especially raucous flock of cranes flies overhead, after being flushed by a Peregrine Falcon.

Unlike other stops along their migration, the cranes are reasonably tolerant of people at Creamerís. They are often within 10-15 feet of the fences that bound the refuge, and frequently cross the public trails on the refuge as well. The photo opportunities are nearly ideal. The long evenings provide sweet light for extended periods. The cranes are active, foraging, dancing, calling and interacting. At sunset, most of the birds move to open water nearby, flying low in a series of small flocks.

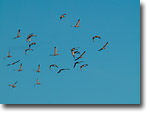

And on one morning, each fall, the birds will be more restive than usual, the dancing and jumping a bit more pronounced, and the calls a little louder and mutual. If the wind is from the northwest, the jumping will gradually extend to short flying hops. The calls will become even more responsive. And with no more warning than that, the whole flock, several thousand strong, will launch, spiraling up, in a kettle a quarter mile across, calling loudly the whole time, spiraling up again and again until there are only distant calls, the birds themselves invisible against the autumn sky. And then the calling will move southeast. It is primeval, natural and astonishing if you are lucky enough to be there to see and hear.

Left behind are Canada Geese and puddle ducks in decent numbers, and sometimes an injured crane, with its mate standing close by. But the fields always seem empty afterwards. The wind always seems a bit colder. And the long Alaska winter suddenly much closer.

Comments on NPN avian photography articles? Send them to the editor.

Jim DeWitt lives in Alaska. He has camped, hiked, skied, fished and photographed in the Pacific Northwest for 46 years.