Photoshop and Nature Photography: How Far is Too Far? |

In the popular view, photography is more realistic than any other graphic art because the camera takes its images directly, optically from reality….However, all art is illusion…and a photograph as much as a painting is a two-dimensional exercise in triggering perceptual responses, not a two-dimensional version of the real world. - Michael Freeman, The Photographer’s Eye: Composition and Design for Better Digital Photos

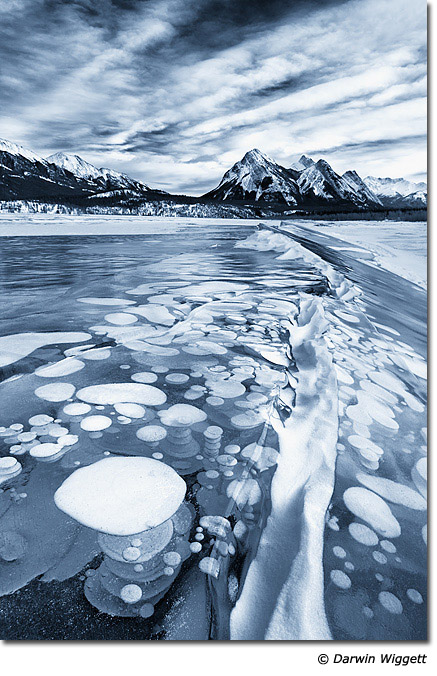

The nature photography world is locked in an unwinnable and pointless debate: how far should you process your nature images before you stray from photography into art? This debate can be seen as a continuum, with those photographers who inherently distrust digital photography altogether (preferring the "purity" of film) occupying one end of the spectrum; let’s call them the Purists. These people shun altering the content or look of a photograph after depressing the shutter (although filters and reflectors may be used in the field) and believe that any processing that does occur is acceptable only so far as it helps to faithfully reproduce what the photographer actually saw in the field at time of capture.

On the other end of the spectrum are the digital manipulators. These types spend as much time (if not more) working an image at their computer as in the field taking pictures. These photographers employ cloning, cross-processing, HDR, and the creation of composite images regularly to freely alter the content and look of their images. Let’s call them the Processors.

The Purists and the Processors have been engaged in a battle that has heated up to the temperature of molten metal since the advent of digital cameras. The Purists accuse the Processors of lying with their wacky creations, and the Processors accuse the Purists of hypocrisy. (A similar debate about how the camera should be used occurred when colour images became possible. Ho hum, plus ça change…) While most photographers would situate themselves somewhere more in the middle of the continuum, enough people exist at each pole to drive plenty of photo forum discussions and blog topics across the whole of cyberspace.

But this entire debate rests on a flawed assumption.

What the Purists and the Processors are arguing about is how much a photograph is or is not reality. But as Michael Freeman points out, all graphic art is an illusion. Graphic art includes paintings, drawings, writing—and photography. No two-dimensional medium is capable of reproducing our three-dimensional world; all attempts are necessarily a representation or interpretation of what is real.

How did this debate even originate within nature photography? Part of the answer lies in the nature of the camera as an artistic tool itself. The camera is designed to record and present visual information derived "directly, optically" from reality. It works in real time, with real objects. Because of how well the camera records and reproduces visual information, it came to be associated over time with communication of visual information to large amounts of people. Thus, at some point, the camera became less associated with artistic expression and more with communication of information. Information (as opposed to opinion) is often seen as objective and neutral; the origin of the camera as a purveyor of fact (reality) is born.

This association clearly continues today. In the September 2009 issue of Photolife magazine, we read the words of renowned aerial photographer and filmmaker Yann Arthus-Bertrand on his work:

I am an extremely dedicated photographer: a beautiful photograph that means nothing is of no interest to me. For me, photography is not an end in itself but a means for transmitting a message, for bearing witness, and for moving things forward. I feel more like a journalist than an artist because I attempt to bring knowledge through my photographs.

The camera has become conflated with the communication of information rather than a platform for artistic expression for its own sake. But this association has not served the photo community well.

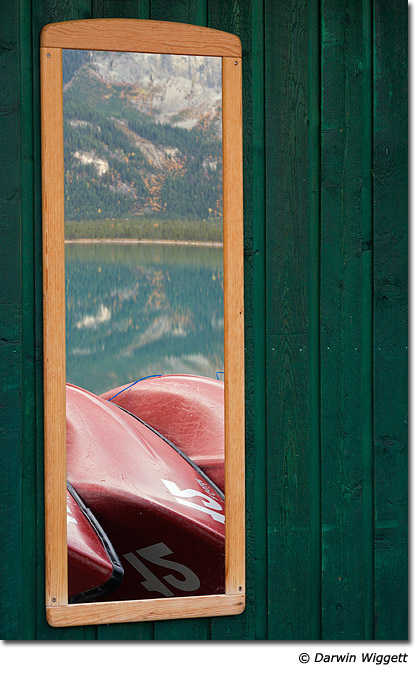

Let’s imagine two photographers standing side-by-side by a mountain lake. Both compose and snap a photograph of the scene before them. Will their images be the same portrayal of reality? Obviously not as even superficially they weren’t standing in the same exact spot. But beyond that give-away, their images are likely to be different in other respects too. One may choose to frame more of the lake and less of the mountain; the other may select a long lens and focus on the mountain’s peak; one may use a consumer camera while the other has a professional camera body. How each photographer makes the image is the first way in which a photograph becomes an illusion of reality. Not only does the equipment used have an impact on the final result recorded, but what each photographer chooses to include—and by extension, exclude— determines what image is rendered. The photographer uses a combination of sensory perception, emotion and conscious or unconscious thought to constrain the real scene in front of him into a two-dimensional illustration.

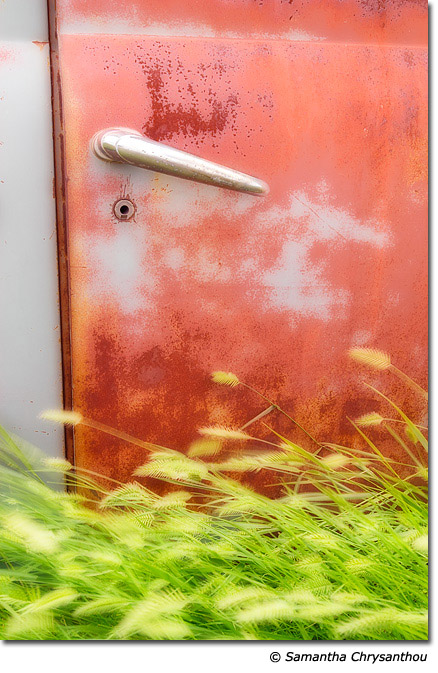

The second way in which a photograph becomes an illusion of reality is when it comes time to turn the data captured by the camera (whether on film or sensor) into a mode capable of being viewed by people. This is where the Purists really get their knickers in a knot. Although many Purists are happy to step into a scene, pick up a stick and throw it away, they will frown on those lazy Processors who decide to just clone out the stick in post-processing. We agree that a good photographer tries to get the best data possible at the time of capture; the principle of ‘garbage in, garbage out’ definitely applies to photography! But does it really matter if you have to walk into a scene to physically remove a stick or whether you clone it out in post-processing?

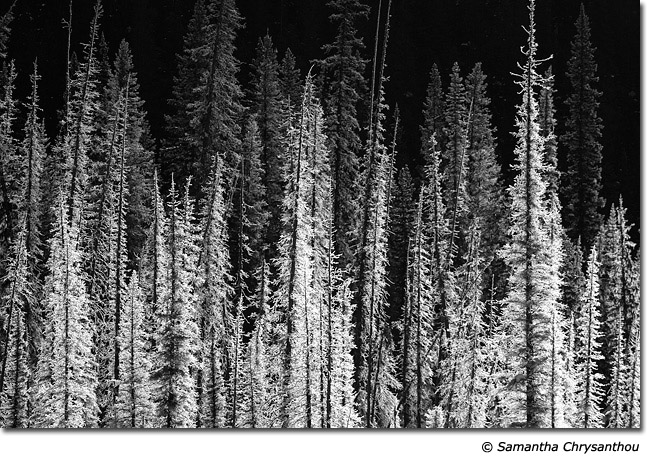

For some magazines it matters. Many editors will not accept nature images that have been ‘digitally manipulated’. Aside from the definition issues that arise with such a term, what does this mean? At the time of capture, a scene can be manipulated or altered from the eye-view of the photographer by the use of special filters, lens choice and "pruning" but the same effect will not be accepted if done at home on the computer? The silliness of this position is revealed when we compare the reaction to traditional, black and white photography to digitally altered, colour images. There is a certain amount of gravitas associated with black and white imagery that is likely left over from the fact that photography was birthed in a world incapable of colour expression. Modern fine art photographers tap into the flexibility inherent in this tradition and present their work in black and white. And yet, if we were truly representing reality, wouldn’t all nature images submitted in black and white be rejected by Purists now that we can shoot in colour? The legitimacy attached to black and white expression survives because of its origins, not its accuracy in communicating reality. It is an allowed exception in the nature photography world to the demand for realism because it was the only way a photograph could be made in the beginnings of the craft.

Framing the debate as a question of "how far" you can go with digital manipulation is a direct result of viewing the camera as a device to record reality rather than a tool for representation or expression of real things. We have become hung up on seeing the camera as a way of communicating information about our subjects and forget that we cannot replicate our three-dimensional world into two-dimensional "facts".

This type of thinking has brought us to a zero-sum game. The Purists refuse to embrace new tools of expression (like digital technology) and are limited in their growth as artists and photographers. (At this point, a short clarification is in order: we do not think all those who shoot in film are Luddites. Medium choice is the artist’s prerogative. We happen to shoot both digital and film for various purposes of expression). The Processors straddle the grey-ish area between photographers and software artists. Neither side can understand the other and believes that their perspective is the morally correct one. Where do we go from here?

We have to re-frame the debate. If we can junk the distinction between communicating information and communicating artistic expression, then we can approach a photograph for what it is rather than what it should be. All graphic art should be judged on how well it expresses its subject matter, and nothing else. If the idea or story the artist meant to convey is successfully told, then the image succeeds. If not, well…time to practice some more.

This means that we all have to adjust to the idea that a photograph is an illusion, a representation, and not literal truth or reality. We as photographers need to do two things: educate the public by not pretending our photographs are "reality" when they are not, and be permissive with each other to avoid that tendency of photographers to pretend they have only "manipulated" their image to make it look "like what I saw." Who cares? The viewer was not there with you when you snapped the shutter. She should be encouraged to engage with the image for its own sake rather than be called upon to compare your work with some objective realty. When we free up photography to be about expression, then this medium will really soar.

Comments on NPN nature photography articles? Send them to the editor. NPN members may also log in and leave their comments below.

Darwin Wiggett is a professional nature and outdoor photographer from Alberta, Canada. You can see more of his work at www.darwinwiggett.com or at www.timecatcher.com. Samantha Chrysanthou was born in Lethbridge, Alberta. After moving for a period of time to northern Alberta, she returned in 2000 to southern Alberta to pursue a law degree in Calgary. After becoming a lawyer, Samantha began to realize her heart was more engaged in capturing the beauty of the landscape around her than debating the nuances of legal arguments in court. She has since left law to pursue writing and photography full-time. She particularly enjoys shooting the prairies, foothills and Rocky Mountains within an hour or so of her home in Cochrane, Alberta. Visit Samantha’s website to view more of her work at www.chrysalizz.smugmug.com.