|

|

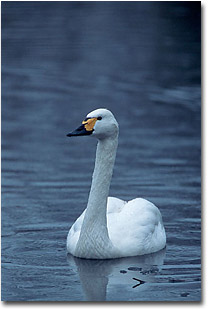

North to South Migration of the Wild Swans

Text and photography Copyright Geoff Simpson

But of all the winter migrants to descend on Britain’s shores from the frozen arctic, there can be few birds that stir the soul like the wild white swans from the north. These are birds of mystery and romance, their evocative calls capturing the spirit of the shortened days of winter when lakes are crusted with ice and the iron grip of frost locks the land. Two species of wild swans visit Britain – whooper and Bewick’s and can be confused with the familiar mute swan that cruises serenely on every park land. Though this species has lived in Britain in a semi-wild state for centuries, it is a native of the Black and Caspian Seas, and was introduced to Britain in medieval times. “The whooper swan is ten times more handsome bird than a tame swan in the eyes of an ornithologist” wrote Victorian naturalist Henry Seebohm, but neither the whooper nor Bewick’s are so graceful as the mute swan. The whooper is a similar size as a mute swan. Its name derives from its wild, whooping calls. Most arrive in late October for the winter after breeding in Iceland. Studies have shown that most birds from western Iceland spend their winters in Scotland and Ireland. Those from eastern Iceland prefer lowland Scotland and northern England, with numerous birds moving further south to the Wash, Cambridgeshire and Suffolk fens and a s far south as Sussex. Two hundred years ago, all wild swans were called “hoopers”. In 1824, ornithologist John Latham described a “Lesser Swan”, not so large as the Hooping swan”. Further research revealed that the lesser swan was a different species, and in 1830, William Yarrel Bewick named it Cygnus Bewickii, in honour of Thomas Bewick, the wood engraver and author of the History of British Birds, who had died two years earlier.

With practice, it is fairly easy to tell a Bewick’s swan from a whooper. It is smaller and has a shorter neck, its body is more compact, and when seen swimming it floats higher in the water. Whoopers’ beaks are much more yellow, extending to the nostril in a V – a Bewick’s beak is usually half-yellow, half-black. It was Sir Peter Scott, founder of the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT), who discovered that the beaks of Bewick’s are as distinct as human thumbprints, making each bird individually recognisable. Studies carried out at the WWT headquarters at Slimbridge, Gloucestershire and on the Ouse Washes at Welney, Norfolk revealed much about their behaviour. They form very close pair and family bonds and cases of divorce are rare, though bereaved birds will pair again. Those who are not ornithologists have long queried why a bird as silent as a swan is linked with singing and music. While mute swans can only grunt or hiss, wild swans are highly vocal, their musical cries are a delight to the human ear. Their calls are similar, but Bewick’s are the noisier of the two, their honks and yelps higher pitched than the whooper’s.

The mated pair act in synchrony, quivering their wings, arching and extending their necks, while at the same time calling continuously. Wild swans are among the longest lived of any birds, with many surviving into their teens and even their twenties. Adults are faithful to their favoured wintering areas and if undisturbed, will come back annually to the same site. Longevity is reflected in their slow rate of reproduction; the annual number of cygnets is seldom more than 20 per cent of the population. Despite this low birth rate, numbers have grown annually in Britain ever since the Protection of Birds Act of 1954. Both species have changed their habits during the last 50 years, increasingly feeding on arable land, usually foraging in harvested fields of potatoes, sugar beet or stubble grain. In winter, some 8,000 Bewick’s and 16-18,000 whoopers are likely to visit Britain. A prolonged freeze in Holland will send more Bewick’s across to England, but in a mild winter, many will remain there. The Ouse Washes are the wild swan capital of Britain, with peak winter counts of more than 5,000 birds. However, spectacular though these great herds are, an unexpected family of whoopers on a remote Scottish hill loch, or a small flock of Bewick’s on a Kentish marsh can be just as thrilling. Where to Watch Wild Swans

The RSPB Reserves at:

Where to Photograph Wild Swans Arguably Martin Mere, Lancashire offers the best opportunities for photographing whooper swans. It’s here that the numbers of birds have increased dramatically over the past 30 years. In 1970 only a handful of whooper swan were visiting Martin Mere and numbers peaked in the winter of 2000 at 2,200 individuals with some 20 Bewick’s being present. If its wild swans in wild settings that you wish to photograph, then Ouse Washes at Welney, Norfolk is your best bet. In terms of exposure I normally using my trusted Canon EOS-1n’s matrix metering dialling in –1/3 compensation for a white bird against any background. However, I resort to using either spot or Canon’s partial metering pattern and open up between 1.3 and 2 stops depends of the light intensity to gain an acceptable exposure should the bird occupy a large proportion of the frame. Lens between 200mm and 500mm are the most useful for portrait and in-flight shots. Although unusual perspective shots may be obtained by a close approach to a mute swan, this is certainly a more difficult type of shot to execute with wild swans. GS - NPN 230 Comments on NPN nature and wildlife photography articles? Send them to the editor. |

|

|

The time is here-the time of magic and excitement! The time of watching and waiting and counting and observing skeins of geese and whirling flocks of waders and those little grey jobs that annually force birdwatchers to delve between the pages of their field guides.

The time is here-the time of magic and excitement! The time of watching and waiting and counting and observing skeins of geese and whirling flocks of waders and those little grey jobs that annually force birdwatchers to delve between the pages of their field guides.  The British Ornithologist’s Union recently renamed the Bewick’s swan the tundra swan. Studies have revealed that the North American whistling (or tundra) swan and Bewick’s are in fact the same species, though I doubt whether most birdwatchers here in Britain will readily adapt this new name despite its appropriateness for a species that nests on the remote Arctic tundra. The Bewick’s swans that visit Britain each winter breed in western Siberia and fly south more than 2,000 miles to reach us.

Their migration south is divided into stages: they gather first along the south shore of the Baltic, then move into the Low Countries before continuing to Britain.

Their stay is short; few arrive before November, and most have started their return migration by the end of February.

The British Ornithologist’s Union recently renamed the Bewick’s swan the tundra swan. Studies have revealed that the North American whistling (or tundra) swan and Bewick’s are in fact the same species, though I doubt whether most birdwatchers here in Britain will readily adapt this new name despite its appropriateness for a species that nests on the remote Arctic tundra. The Bewick’s swans that visit Britain each winter breed in western Siberia and fly south more than 2,000 miles to reach us.

Their migration south is divided into stages: they gather first along the south shore of the Baltic, then move into the Low Countries before continuing to Britain.

Their stay is short; few arrive before November, and most have started their return migration by the end of February. While mute swans are unsociable, aggressive birds, wild swans are highly gregarious, demonstrative and noisy. Vocal signals and displays are used to keep the family and flock together.

While mute swans are unsociable, aggressive birds, wild swans are highly gregarious, demonstrative and noisy. Vocal signals and displays are used to keep the family and flock together. The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust centres at:

The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust centres at: