Composing With Light - Part 1 |

You have to get away from relying only on the subject. Light is the imagination's main tool. It is something you work with in defining anything you want to, whether subject or landscape. - David Muench, Outdoor Photographer, June 1996

Introduction

Light is the photographic medium par excellence; it is to the photographer what words are to the writer; color and paint to the painter; wood, metal, stone, or clay to the sculptor. - Andreas Feininger

Every art, every craft, makes use of an essential material, a material that is at the foundation, of that art or craft. It is the nature and the treatment of this fundamental material that will define the quality of the finished product.

For the winemaker, this essential element is the grapes. It is not the recipe used in the creation of the wine, nor the barrels in which the wine is kept, nor the aging process, nor the conditions in which the wine is aged, although all of these are very important. The material at the basis of wine making is the grape. Without grapes there would be no wine, no matter how skilled the winemaker, how good his equipment or how extensive his knowledge might be. And without good grapes there would be no good wine. A master winemaker knows more about grapes than about anything else in his trade. A master winemaker loves grapes and everything that surround their growth, their history, and a million other details that, to those who do not share his passion, seem uselessly boring and unnecessary to remember.

For a woodworker, this essential element is wood. It is not his tools, it is not his technical abilities or his skills, and it is not his years of experience, although again all of these are extremely important. This essential element is wood. A fine woodworker seeks to know as much as he can ever know about wood, because it is through this knowledge that the finest woodworks can be achieved. A fine woodworker loves wood.

For a chef this essential element is the products that are to be cooked. It is the vegetables, the fruits, the poultry, the meats, the cheese, milk, eggs, butter, spices, herbs and countless other products that are necessary to complete each dish. It is not the pots and pans, it is not the recipes, and it is not the years of training, although here too all of these are very important indeed. No. It is the products used in the making of these dishes, because without the finest products one cannot cook the finest dishes. No amount of sauce, or spices, or skills can turn a poor quality product into a great dish. Nothing can duplicate the taste of a grain-fed chicken, raised in the farmyard and allowed to roam freely. Nothing can duplicate the taste of garden-grown, fertilizer-free vegetables. Nothing can take the place of hormone-free beef, whole, non-pasteurized milk and butter. To the uninitiated these are simply unnecessarily expensive and troublesome to purchase. To a chef they are indispensable.

This essential material does not have to be physical. For example, to a musician this essential element is sound. Regardless of the instrument played, a fine musician pays more attention to the sound produced by his instrument than to any other variable. In that respect the instrument itself is also important because it is the instrument that creates the sound. But the love of the musician for sounds exceeds the love of the musician for his instrument because sound can exist without instrument. Sound is in nature, in the wind, the rustle of leaves in the forest, the babble of a creek, the sounds of birds, of animals and of other beings. The instrument is a way to reproduce sound but the instrument is not all that sound is. A musician therefore seeks to learn as much about sound as can be learned. A musician loves sound, both sounds created by nature and sounds created by musical instruments. For a musician the quality of the sound is of primordial importance.

For a photographer this essential element is light. It is not the camera, or the film, or the digital processing software, or the chemicals used in the darkroom, although all these are very important. It is light, because without light there would be no photograph.

Photography, etymologically speaking, means writing with light, from the Greek Photos, light and Graphos, writing or drawing. Light is photography and photography is light. A fine photographer who desires to advance his art as far as possible will seek to learn as much about light as possible. He will study light more than he will study any other aspect of his art. Light will become his obsession and the focus of his attention. Not just natural light but any type of light, be it artificial or natural light, be it the light of the sun or the light of a tungsten bulb, the light of the stars and the moon at night or the light of a flickering candle. Light, in all of its manifestations, is the photographer's blessing, the primordial element without which there would be no photographs. A fine photographer loves light as much as a fine winemaker loves grapes, or a fine woodworker loves wood, a fine chef loves natural products and a fine musician loves sound. For a photographer the quality of the light is the one thing that can never be ignored. It is everything.

Without these essential elements there can be no trades because all trades rely on these primordial elements that defines their existence. Everything else is built upon that one thing: tools are developed around it and focused on how to best use this essential element. Knowledge is developed around it and focused on how to best work with this essential element. Education and training is focused on the nature of this element, on its particular characteristics and on the unique creative possibilities that it offers.

The audience often focuses upon the finished product: upon the wine, or the music, or the dish or again the photographic image. The chef, the artisan, the musician, the artist, focuses instead on the essential element that is the foundation of their art. They know that the quality of the final product is dependent upon the quality of this foundational element. They know that good grapes, good produce and meats, great sound quality, beautiful woods and great light have no substitute. The outcome of their efforts, the quality of the final product, depends upon the quality of this element. They know that the quality they seek can only be found by being able to recognize this element in its finest implementation, by knowing where to find it and how to use it.

Light and composition

My first thought is always of light. - Galen Rowell

Because light is the main element in photography, light cannot be removed from composition. Why? Because light is part of composition. If fact, I would go as far as to say that in photography, light is composition. As photographers, we compose first with light and second with objects and elements. Why? Because without light we could not see these elements and these objects. We have to have light not only to photograph but also to see.

However we need more than just light, just like a chef needs more than just produce, poultry, spices, and so on. We need great light. In this sense the quality of the light is what we really need to learn about.

Quality of light determines image quality. Great light is the ingredient behind every great image. Of course, great light alone is not enough. I have been in situations where great light was present, and yet I was unable to compose a great photograph, or even a photograph at all. At such times I was overwhelmed by the beauty of the light and lost myself in experiencing the light instead of photographing the light. Nothing wrong with that, except that one needs to go past this stage if one is intent on becoming a better photographer.

Certainly, experiencing stunning natural light, such as a rainbow at sunset, or a fantastic sunrise, is a stage in one's development as a photographer. It is a stage of learning and of emotional reckoning. It is a stage at which one takes stock of the awesomeness of natural light. It is a stage during which one discovers what nature can create when nature puts forth its best show for a few seconds of fleeting light. However, this discovery is not the final stage. The final stage is being able to experience a tremendously beautiful natural event and still keep your wits together so that you can not only photograph it, but you can also compose an image that takes advantage of this awesome light in such a way that you can share both your emotions and the natural beauty that you witnessed with your audience.

We must therefore look at the quality and direction of the light when evaluating the potential of a scene for a strong composition. Eventually, we have to physically see what light can do to fully evaluate the potential for composing images. Why? Because light can sculpt the landscape in ways that are difficult to imagine. In other words, it is difficult, not to say impossible, to imagine what light can do to a scene. I have witnessed many instances of this fact, either while being at a location myself and seeing something I had never seen before, or when looking at photographs taken by other photographers and seeing a lighting situation that I would never have imagined could happen. Light can do things to a landscape that are beyond what we can imagine. We just have to be there on the right day at the right time and have the knowledge and the experience required to capture it in a meaningful photograph.

How do you find the best light?

You only get one sunrise and one sunset a day, and you only get so many days on the planet. A good photographer does the math and doesn't waste either. - Galen Rowell

The main subject that I want to cover is learning how to find good light, or the "best light" if there is such a thing. I say that because, eventually, what "best" means varies from one photographer to the next. Eventually, what we want to find is the best light for a specific personal style. While we will tackle the subject of personal style later on, we can already say that light is an essential component of your personal style. What light you like to work with, what light you consider to be the best for your work, and what light you find most exciting, are personal choices rather than absolute choices. These are matters of taste that are bound to vary from one photographer to the next.

Finding good light is both a matter of personal experience and knowledge and a matter of using the right tools. We will start with experience.

Bad Weather

The first thing to keep in mind is that what makes for good light in photography is very different than what makes for good light in other aspects of our lives. In other words, we will choose entirely different times to be out in the landscape depending on whether we want to take good photographs or whether we want to go on a picnic to take just one example.

This is best exemplified with the fact that, in photography, bad weather often creates great opportunities for good photographs. In other words, bad weather equals good photographs. By bad weather I mean active weather. Active weather is weather that is changing quickly. The time after a storm, or between two storms, is an excellent example. If you have a heavy rainstorm, and the storm is coming to an end, with the clouds starting to open up to let the sun shine through, that time, right there, is one of the best times for photography you will ever find.

The photograph below was taken in such a situation. A heavy rainstorm fell on Canyon de Chelly all afternoon. The clouds were dark, menacing and very impressive, and I knew that if the sun were to shine through the clouds we would have an incredible photographic opportunity. So I drove to Tsegi Overlook, only 10 minutes away from where I lived, and I waited, hoping that the sun would come out. When it did, I was able to take this photograph. The span of time between total overcast and full sunlight, the transition time from the storm to a sunny afternoon, lasted only a couple of minutes. That was all that I had and that was all I needed. Photography freezes time, and when looking at this image one has no way of knowing (nor does it matter) whether this lighting situation lasted a minute or an hour. All that matters is the graphic quality of the light and the drama that this light created. A few minutes later this scene became as commonplace as it can be, and looked the way it looks on countless afternoons every year. But that one minute, captured in this image, was incredible.

Clearing Storm over Canyon de Chelly

In this image notice how the patterns of light and shade help define the depth of the canyon and create three-dimensionality in the entire scene. In many ways, the light defines the composition of the image. It shows which rock formations are in front or behind each other. In other words, the light gives depth to the image. If the whole landscape was in the light, or if the whole landscape was in the shade, it would look flat and two-dimensional. By being partly in the light and partly in the shade, it has depth and looks three-dimensional.

The light also outlines what is most and least important in the scene. By definition, the human eye will first notice the areas of an image that are either the brightest or that have the most contrast. Here, these areas are the canyon wall and the clouds in the middle of the image, in the distance, behind the river. These areas are the ones emphasized by the light. They are also the most important in the composition because they are the ones with the most remarkable shapes in regards to the canyon walls. Because of the patterns of light and shade in the clouds, the clouds become very important and attract the eye considerably. They take on much more importance than the foreground which is in the shade and where little drama, if any, takes place. This foreground is fairly empty of recognizable shapes, and not very important. It plays a lesser role, a fact emphasized by the light that is soft and non-dramatic, in that area.

In other words, the light not only makes this photograph, the light composes this photograph. The lighting patterns unique to this natural lighting event in Canyon de Chelly create what I consider to be one of the most perfect compositions for this specific location. To prove this point let me say that I have taken countless other photographs of this same location, using the same composition or one very similar to it, and that although I have many other nice images, none come close to the drama and the impact of this one.

Bad weather is a tremendous help in our quest to find good light. The weather at the end of a storm is particularly propitious. If you are in the field, and the weather is bad, don't retreat to your house or to your hotel room. Instead, wait out the storm and look at the sky in the direction of the sun. If something is to happen, it will happen there. Try to predict what might happen, meaning if and when the sky will open up and the sun shines through the clouds, then think of a nearby location that would be ideal for this light, and go there. Eventually, you will be rewarded with great photographs. Maybe not the first time, or the second time, or even the third time, but eventually.

Chiaroscuro

There are other instances where light makes the photograph, or, to put it more in terms of our discussion in this chapter, where light creates the composition of the image.

One such situation is Chiaroscuro, clair obscur in French, light and dark in English. I like the Italian and French terms the best because, to me, they describe the light better than the English term by placing together two terms that are not normally associated. We talk of things that are light, and we talk of things that are dark. We talk of things that are lit, and we talk of things that are not lit. We do this all the time, but only rarely do we talk about things that are, at the same time, lit and not lit, or dark and light.

That is what chiaroscuro is. Lit yet unlit, dark and yet light. Chiaroscuro is a contrast, an opposition of two lighting situations that are opposite to each other. Chiaroscuro is a conflict between lightness and darkness. And the best images composed with chiaroscuro are those in which this conflict is never quite resolved, no matter how long we look at them and study the composition of the image.

Chiaroscuro in Antelope Canyon

In the image that I selected to illustrate this point, Chiaroscuro in Antelope Canyon, the light source is a beam of sunlight that shines into a narrow canyon through an opening at the top of the canyon. When the light reaches the floor of the canyon, it bounces off the floor. By reflecting the beam of sunlight, the canyon floor becomes a virtual light source.

Reflected light can be quite powerful. The full moon is an excellent example. The moon does not generate light, it reflects the light of the sun. However, the sunlight reflected off the moon is powerful enough to illuminate the landscape and create shadows at night.

Here, the light beam reflected off the canyon floor is powerful enough to light the canyon from the bottom up. Because of the depth of the canyon, this light does not reach all the way to the top of the canyon. However it does go up quite a ways, and by doing so creates an inverted lighting situation in which the canyon is lit more brightly from below than from above. In nature, we are used to seeing objects lit more brightly from above than from below. Therefore, this inverted lighting situation gives this image a strange and unexpected look.

The Chiaroscuro effect in this image is created by the juxtaposition of brightly lit areas and deep shadows. The transition from one area to the other takes place over a short distance, making these two areas almost touch each other. As viewers, we see these bright and dark areas as neighboring values and our eyes go from one to the other, back and forth, in rapid succession. The act of comparing light and dark, and the difficulty of deciding which of the two is the most important, is what chiaroscuro is all about. If one of these two areas takes over, the effect is gone. But if this ambiguous light quality is maintained, the effect is successful.

Bad Weather and Chiaroscuro are but two examples of composing with light. Later in this essay we will look at other examples of how light can transform a common scene into a unique natural event.

Right now we are going to look at how we can predict when and where the sun will rise and set. We are also going to learn which tools can help us study the light and know when to be at a given location at the time of our choosing.

Finding Sunrise & Sunset Times

It is light that reveals, light that obscures, light that communicates. It is light I "listen" to. The light late in the day has a distinct quality, as it fades toward the darkness of evening. After sunset there is a gentle leaving of the light, the air begins to still, and a quiet descends. I see magic in the quiet light of dusk. I feel quiet, yet intense energy in the natural elements of our habitat. A sense of magic prevails. A sense of mystery. It is a time for contemplation, for listening - a time for making photographs. - John Sexton

Knowing The Path of the sun in the sky through the year

In our quest to find the best light and to learn to compose with light, knowing where the sun is going to be at a given time of the year is essential. It is essential because the sun's position in the sky varies greatly from one time of the year to another. The greatest difference is between the summer and the Winter Solstice, between December 21st and June 21st. These are the times of the year when the sun is, respectively, the furthest south and the furthest north.

I am here speaking about the sun's position in the northern hemisphere. If you live in the Southern Hemisphere, simply invert what I just wrote. In Australia for example, the Summer Solstice will be on December 21st and the Winter solstice on June 21st.

And of course, if you live on the equator, there is hardly any difference between winter and Summer solstice. The sun stays virtually straight overhead all year long. In that case most of the remarks made in this section simply do not apply.

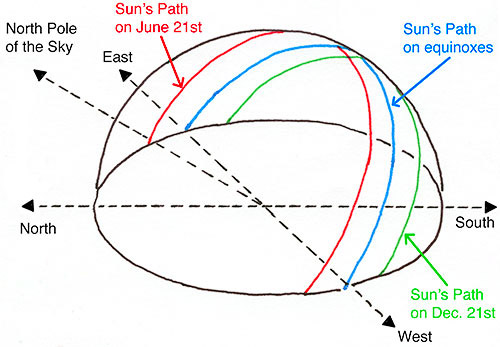

I will continue my comments from the perspective of someone living in the northern hemisphere. In such a situation, the position of the sun in the sky, across the calendar year, is as shown on the graphic below:

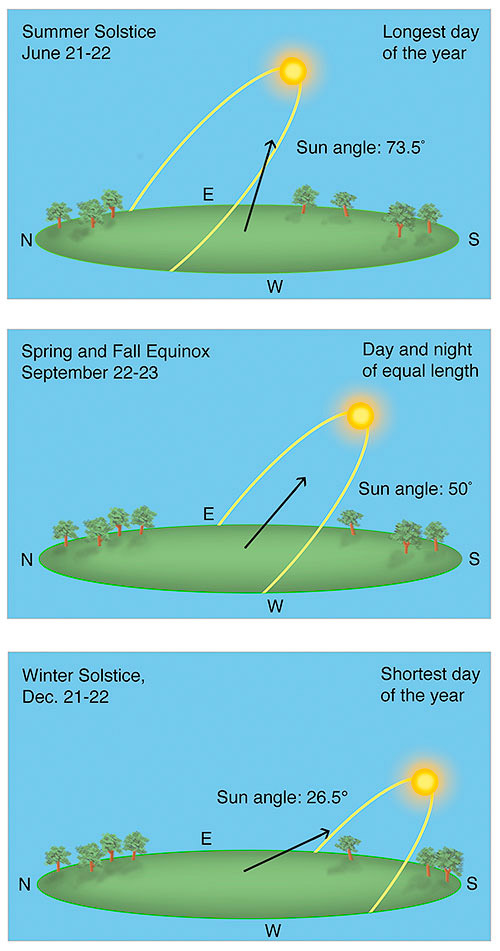

The three drawings below show the position of the sun on the Summer Solstice, the Equinox and the Winter Solstice. The Equinox is the time of year at which the sun is precisely half way between the winter and Summer Solstice:

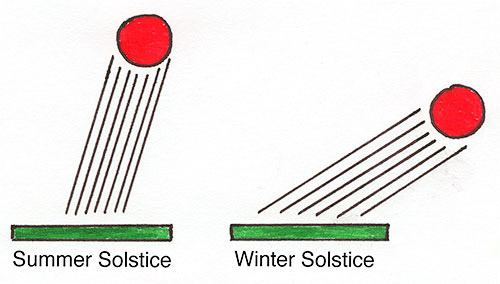

The reason why the sun's position in the sky is so important for photography is because the position of the sun greatly influences the angle of the sunlight. The graphic below shows the angle of the sunlight on the Summer Solstice and on the Winter solstice, when the sun is at the zenith, which is at the highest point in the sky for any given day:

As you can see the angle of the sun is very different on the summer and the Winter Solstice. On the Summer Solstice the sun is shining nearly straight down when it is at the Zenith, while on the Winter Solstice the sun is shining at a very steep angle.

You can think of the Zenith as being noon. While not totally accurate due to variations between time zones, this is nevertheless helpful. The whole point here is that, for photography, having light shining onto the subject at a steep angle is better than having light shining straight down. This is why sunrise and sunset light are so good for photography. At sunrise and sunset the sun shines onto the landscape at a very steep angle. In fact, at the point where the sun just comes up or goes down over the horizon, the light is literally horizontal, meaning it is shining onto the subject at the steepest angle possible.

This also means that if you photograph during the summer, around the Summer solstice, you will have vertical light most of the day and horizontal light only at sunrise and sunset. This limits the time during which the light is most propitious for photography. Basically, in the summer months, you have an hour after sunrise and an hour before sunset to photograph in the best light. After and before these times the sun is at a steep angle and the light quality is far less propitious for good photography.

On the other hand, if you photograph during the winter months, around the Winter solstice, you will certainly have horizontal light at sunrise and sunset as in the summer months. However, you will also have light shining at a steep angle onto the subject just about all day long. This means that you will have far more opportunities for good light during the winter. In fact, in the winter, you can sometimes photograph all day long with relatively good light. While sunrise and sunset will continue to offer the finest light in the winter, daytime can also be used for successful photographs under direct light.

Alain's Field Notes

I spend a considerable amount of time studying the location where the sun rises and sets, across the year, for each of the locations that I photograph. Doing so is time consuming but worth it because it helps me plan my photographs and allows me to know when to be there to get the light that I am looking for. In other words, the time I spend at home planning a shoot saves me time in the field because I know exactly when to be there at the perfect time. As a result I spend less time on location waiting for the light.

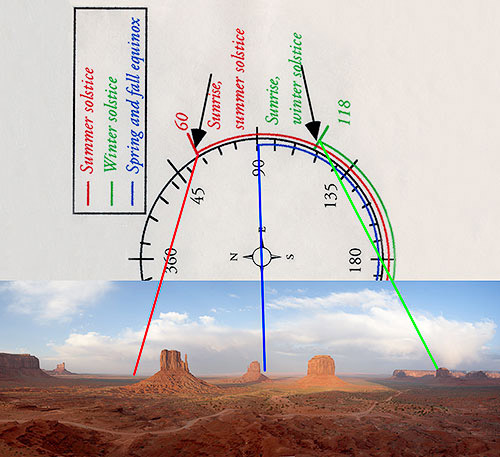

Below are notes and diagrams that I made for a specific location: Monument Valley, located on the border between Utah and Arizona. These are scans of my notebooks together with a panoramic photograph of Monument Valley.

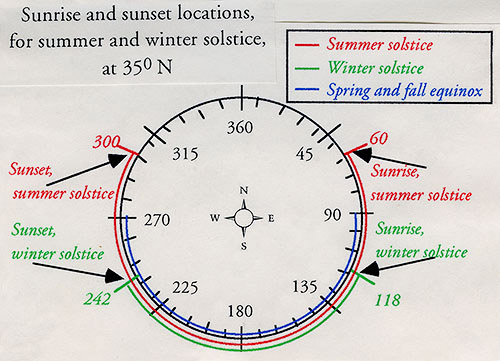

The first diagram, below, shows the azimuth, in degrees, where the sun will rise and set on the winter and summer solstices and on the equinox. The azimuth is the location on the horizon, in degrees, where the sun will rise, set or be at a given time of the day. The azimuth is found using a compass by pointing the compass in the exact direction you want to measure, and then reading the azimuth, in degrees, on the compass. The azimuth is measured from 0 to 360 degrees, the circumference of a circle. This circle is a metaphorical representation of the earth since the earth is circular.

On this diagram the red line represents the path of the sun during the summer solstice, the blue line represents the path of the sun during the equinox, and the green line represents the path of the sun during the winter solstice.

A lot of information is contained in this simple diagram. First, the difference between the azimuth of sunrise and sunset between the summer and winter solstice is 58 degrees (118-60 or 300-242). This is a very significant amount that accounts for the extreme difference in light angle between summer sunrise and sunset, and winter sunrise and sunset, at Monument Valley.

It also explains why one will not get the same lighting at all if one is there in the summer or in the winter. If you saw a photograph of Monument Valley taken in the winter, and you go there in the summer planning to take the same photograph, you will be disappointed because the light will be totally different!

This information also allows you to know where the sun will rise and set at any given time of the year. The diagram and the photograph below best show this:

Monument Valley Panorama with sunrise azimuths for Solstices and Equinox

In this diagram and photograph, the red, blue and green lines on the diagram are connected to the corresponding locations on the photograph where the sun will rise on the summer solstice, the spring and fall equinox and the winter solstice (the sun rises in the same place on the spring and the fall equinox). The photograph was taken looking straight East, where the sun rises. A similar photograph and diagram could be made looking straight west, where the sun sets. However, at this location I am interested in photographing towards the East, which is why I made this diagram looking east. Do know that this information is valid for a very long time since the locations of sunrise and sunset will not change during our lifetimes.

Below are two photographs exemplifying the extreme difference that I discussed in my presentation of the diagram above. Both photographs were taken at sunrise. The first photograph was taken on the Summer Solstice while the second photograph was taken on the Winter Solstice.

In the first photograph the sun rises to the left of the Left Mitten while on the second photograph the sun rises to the right of the Right Mitten. On the Winter Solstice the sun rises so far to the south (on the right in the photograph) that it is not even visible in the image. However, the sun streak (or lens flare) in the photograph points to the location where the sun is rising.

The two buttes in Monument Valley are called the Left Mitten and the Right Mitten because they are shaped like mittens. Mittens, or mitts, are gloves with a thumb and no other fingers.

Summer Solstice Sunrise at Monument Valley (June 21st)

Winter Solstice Sunrise at Monument Valley (December 21st)

Comments on NPN landscape photography articles? Send them to the editor. NPN members may also log in and leave their comments below.

Alain Briot creates Fine Art Photographs, writes books, teaches workshops and publishes DVD tutorials on composition, printing and marketing photographs. You can find more information about Alain's work, writings and tutorials on his website at http://www.beautiful-landscape.com You can also subscribe to Alain's Free Monthly Newsletter. You will receive 40 free essays written by Alain when you subscribe.