Wild Horses of the Carolina Coast |

The colors of dawn began to stretch across the heavens in a Homeric-like display of pink and magenta. Like Homer's famed Odysseus, we watched these rosy fingertips unfurl from the deck of my boat. The sun had yet to rise and the coastal winds that characterize and shape this landscape were still. Staring out over the water as my skiff slipped across the surface at 25 knots, it felt as though Heaven and Earth had merged into one seamless mirror of each other. The sublimity of the scene was broken only by the dorsal fins of the coastal bottlenose dolphins that were hunting along the edge of the shoals we skimmed past.

We were navigating a stretch of water known locally as "the Drain," for the intensity of the currents here seemed as though the entirety of Core and Back Sound were draining from this one small break in the barrier islands. Notoriously dangerous, and predictably unpredictable, this was the type of conditions - shallow and chocked full of sandbars - that my boat was specifically design for. Drafting only 8 inches of water on plain, we need but enough water for the prop to spin in order to run. Up ahead the Cape Lookout Lighthouse shone bright, standing sentinel over this stretch of the Graveyard of the Atlantic like a beacon of hope for seagoing vessels.

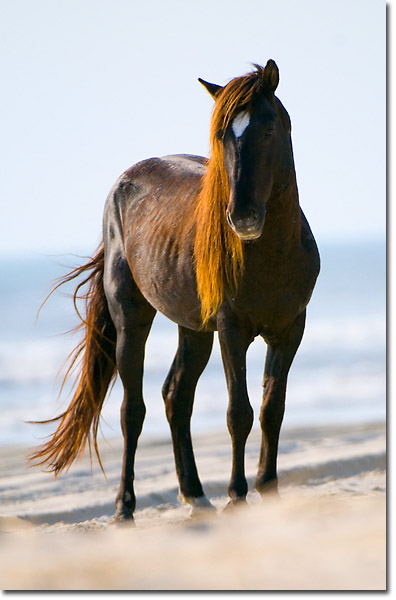

This is the last place on Earth that my customers would have thought to come in order to photograph wild horses, yet here, on these remote islands live one of the oldest known populations of wild horses in North America. Known officially as the Banker horse, these smallish yet stout horses have survived the very worst of Poseidon's wrath along these islands for some 500 years.

When one thinks of Wild Horses, typically we envision the iconic images of the West, sun setting over the horizon, dust rising into the air, maybe the dramatic snowcapped peaks of the Grand Tetons - as portrayed by Disney of course - stand in the scene. It is true that the modern day horse came from this landscape, as there is no other species of animal that is as well represented in the fossil record of the American West. With the end of the last ice age however, the horses of the American landscape, along with wooly mammoths and saber-toothed cats went extinct. It would take the discovery of this so called New World by European explorers before horses would once again return to their ancestral home.

It was along the Atlantic coast that European civilization first crashed into the North American continent, and thus it was here that Europeans would reintroduce horses to this hemisphere. For countless reasons horses were abandoned upon these shores, tossed overboard to lighten the loads of grounded ships, and stood as the only surviving members of lost and forgotten attempts at colonization. The preceding centuries of genetic isolation would combine with wind, water, sand, salt, and storms to create a breed of horse quite unlike any other on Earth.

Pulling up to a series of marsh islands formed many decades ago from a massive hurricane that swept across Shackleford Banks, we could see a band of horses standing about two feet deep in the water staring out at the lush shoots of smooth cordgrass rising up above the water's surface some distance away. Undeterred by the obstacles of deep water, swift currents, and a full fledge bull shark nursery, the horses began to push out into the estuary. The water rose first up to their chests, then to their necks. Within seconds however, their hooves kicked free from Terra firma as they began to swim for distant islands as so many generations of their ancestors had done before to survive.

My customers froze in place. These folks were all seasoned photographers with countless hours under their belts spent photographing mustangs of the arid west. Yet here, along the edge of the sea, as black skimmers buzzed the surface of the water and dolphins surfaced for air, they watched wild horses act out one of the most profound behavioral adaptations they had ever witnessed.

Seeing their apparent shock at what was unfolding, I tossed the anchor into the water and jumped overboard into the shallows to secure the boat and start hoisting down gear. When it comes to working with these horses, boats are just for traveling - we photograph from the water.

With tripods shouldered, we began our wade out across the flats to put ourselves in position to take advantage of the morning light. Sure, we could have done all of this on the boat, but I would much rather be down here, in the water and at eye level with these horses, than hovering above - rocking in the boat. Besides, this is wildlife photography - you have to immerse yourself in the environment (pun intended) for the full experience.

Working in watery environs takes special precautions and even specialized gear. When you are toting thousands of dollars' worth of camera gear - which I hear does not mix well with salt water - you need to take every precaution necessary. As Murphy's Law dictates, if it can happen, it will happen. Personally I look at mishaps as a matter of numbers, play with fire enough times and eventually you will get burned. For this reason, and the fact that many photographers are not used to, or particularly comfortable, working in and around water, the topic of gear inevitably becomes a major pre-trip discussion and on site lesson. For this reason, I will hit on a few gear related points below.

Without a doubt, the first and most important consideration when working around water is having the means to keep your gear dry and secure while in transport. For this reason, dry-bags are key anytime you are working from boats, as are Pelican cases for the extra added bomb proof measure of security. On the boat, these items are what will protect your gear from spray or an unexpected wave that may roll over the bow. I keep my camera body locked onto a lens of choice that the situation will most likely demand. Therefore I want a dry bag that can hold a large lens and camera body combo and can be accessed very quickly - just in case. Thus I opt for a traditional roll top dry-bag for the task and keep all other gear stored away in a Pelican case.

When the boat is close by or I have a first mate to keep pace with us while in the water, I simply shoulder my tripod and press on. When I am working away from the boat however, I use a gear sled to store my gear in that I can pull along behind me. These sleds are designed for dragging gear behind you on the snow, but work just as well in the water since they float. I have seen some photographers use black mortar mixing bins that you can pick up from most any hardware store, but I prefer the sleds since they store more gear and the front of the sled it sloped up which allows the sled to pull through the water with ease. Bigger is often better with these things and so I recommend the larger sleds such as those made by Shappell. Be it wading through ice chocked waters in the winter while photographing waterfowl, or sloshing around the sloughs and shoals of the barrier islands in search of horses - these bins are one of the most useful pieces of gear you can have. Tripods, blinds, dry-bags, camera gear, coffee... you name it, these things will float it.

Another very important, yet often overlooked piece of gear is foot attire. When working along the Crystal Coast, the National Park Service states that the number one reason for evacuations out of the backcountry here is slicing and dicing feet on oyster beds. Oysters, muscles, sea urchins, and a litany of other offenses abound in the water that can make a quick mess out of the feet of unsuspecting visitors. Really though, this is most places where you have people wandering around in the water - regardless of where you are. For foot protection in warm water like this, I recommend the closed toe sandal hybrids made by Keen. I have ripped through a number of other high dollar sandals over the years while working in the water, but Keens have held up through it all.

We work hard to keep our cameras and lenses high and dry in the water, but one piece of equipment that we will inevitably plunge down into the water and God only knows what below, is our tripod. A new piece of gear on the market is water socks for your tripod legs. These socks seem to work best in stationary situations, say for instance - photographing a rookery from the water. However, when you will be moving around a lot and continuously adjusting the height of your tripod, the socks really seem to constantly be in the way. The last thing you want is to be fighting with these things when the action is hot. So for me, there is nothing better than good old soap and water to wash down the tripod at the end of the day.

The horses that we were following had by now swum across the series of shoals and channels to a preferred marsh island to graze - a most improbable scene for sure. With a seemingly endless expanse of water stretched out before us, here was this small harem of wild horses standing surefooted upon an island that was not a quarter acre in size. Spurred on by the demands of nutrition, these horses had overcome a significant obstacle all in the name of accessing greener pastures.

Assessing the scene before us, it is not hard to understand why that capturing the essence of their environment is paramount to photographing wild horses. Horses in the water, horses galloping across the beach, fighting atop the dunes, standing at the edge of the ocean blue with mane adrift on the wind - these are the images of wild horses. These are the images that put horses of this coastline in their place, and separate them from domesticated and western wild horses alike. Intimate portraits are fun, but I want you, the viewer, to not only know immediately that you are looking at wild horses, but I also want you to understand the distinctiveness of these horses and the realities of what it takes for them to survive.

For this reason, big glass such as 500 and 600mm lenses are not only not needed, but they often become too cumbersome and hinder what you can do and how quickly you can do it when photographing these horses. Instead, I opt for a combination of a 70-200 f/2.8 and a 200-400 f/4 VR lens. My customers shooting Canon tend to be happy with just a 100-400mm lens throughout the duration of multiday trips.

These horses are large creatures and relatively habituated to the presence of humans. These horses can also move around at 40mph. What may have been a beautiful composition in the viewfinder with a long lens attached at one moment, can turn into nothing but heads and necks very quickly if that stallion you were photographing charges an offending stallion. For this reason, the versatility of a zoom lens is critical in these conditions.

As is the case when photographing any species of wildlife, the more you know about your subject beforehand, the better prepared you will be to anticipate behavior and respond accordingly while in the field. In other words, chance favors the prepared mind. So do your homework, learn some basics of horse biology and their social dynamics.

Horses are social creatures living within groups that we call harems. A harem is usually made up of 2 to 5 mares and one stallion. Occasionally you will have a multi-stallion harem with an alpha and beta stallion, however this is not the norm. Young males, or colts, are typically kicked out of the family group at around the age of 2. From here on they will roam by themselves or more likely join up with other young single male horses to form what are called bachelor groups. These bachelor groups in tern cause all the problems that you would expect any roving gang of young teenage males of any species to cause. Bachelors run, fight, play, and in general, are constantly working out the specifics of the future hierarchy of their species.

Stallions fight to make a living. Every harem that you see was formed from that stallion fighting tooth and nail to steal those females from another stallion. These boys will fight to the death at times and their bodies carry the scars of this lifestyle. For this reason, stallions do not take kindly to other stallions being in their presence. The one exception is when males form bachelor groups - as long as you keep the females out of the mix than the boys get along just fine. Once these males begin steeling girls for themselves however they will not tolerate any other males in the area.

So what can you do with this information in terms of photography? If you understand the dynamic nature of bachelor groups, than when you locate one, you know that you may be well rewarded to stick it out with that group since you are more likely to witness the explosive action that we all prefer to capture. Harems spend the overwhelming majority of their time eating and sleeping - not as much action here. Likewise, if you are photographing a harem of horses, be on the lookout for another group that may wander within sight. The stallion will usually know this before you do, and you can see it in his posture - head up, chest out, muscles tensed, ears forward, staring in the direction that the other horses will most likely materialize.

The coast of North Carolina has been blessed with not one, but three distinct populations of wild horses that are eking out a living on the barrier islands. Each one of these groups offers something completely different for the photographer in terms of behavior, adaptations, and most importantly - landscape. There are quite a few logistics that must be worked out to access the different groups, such as driving on sand, handling a boat, and protecting your gear, but once overcome, the wild horses of the Carolina coast offer you the opportunity to photograph these animals in the most exotic of settings in North America.

Comments on NPN wildlife photography articles? Send them to the editor. NPN members may also log in and leave their comments below.

Jared Lloyd is a professional wildlife photographer, nature writer, environmental photojournalist, outdoor educator, workshop leader, husband, father, and human living on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Jared's work has been widely published in magazines, newspapers, trade journals and other publications in print across North America.

Jared Lloyd is a professional wildlife photographer, nature writer, environmental photojournalist, outdoor educator, workshop leader, husband, father, and human living on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Jared's work has been widely published in magazines, newspapers, trade journals and other publications in print across North America.

For more of Jared's photography and writing, visit his website and photographer's journal.