|

|

All rights reserved.

It was also then that I wondered how safe the cubs were. What was the likelihood of their being discovered by a wandering leopard or a clan of hyenas, both implacable enemies, who would not hesitate to kill unprotected lion cubs? Such things happen, but not this night. When the lionesses had had their fill, one of them, probably the babysitter, went to fetch the older cubs to the meal. Later, the younger cubs were brought in, too. Many weeks later, I was reminded of my thoughts about the cubs' safety when I started hearing piecemeal accounts of a disastrous hunt by these lionesses of the Selinda Reserve, in northern Botswana. It happened two months after my visit. The mild, dry winter was over, and the time of heat and dust was approaching in the lead-up to the rainy season. It was still a land of plenty, though, as the heart of Selinda is Zibalianja lagoon, an extension of the Linyanti swamps on the border with Namibia. The reserve has existed only since the mid-1990s, after years of uncontrolled hunting had almost turned it into a wasteland. The water makes it a paradise for wildlife, from elephants to bushbabies, and for many of the browsers and grazers in between - and for the predators, the big and small cats, the hyenas and wild dogs. So the lionesses went hunting, leaving their cubs, now numbering 14, hidden in the reed beds of the lagoon. They were safe there, for sure, but their fate was sealed. A fire, probably started by lightning, had swept across the border from the Caprivi Strip, into the reserve's tinder-dry grassland and scrub. The hunting party found itself either on still-burning or recently burnt ground, effectively treading hot coals. It's not known whether they tried to go forward or back to escape. The two oldest lionesses, thought to be about 10 years of age, suffered only minor injuries, perhaps because they had experience of fire and escaped more quickly. The seven others, only half their age, had their feet severely burned. So began an ordeal that in the next 10 weeks wiped out a generation of the Selinda pride.

I dubbed Selinda 'the land of lions' because of this flourishing pride. It was controlled by a coalition of five males, as strong a guardianship as one could find. Now, weeks later, I was hearing that the lions were in trouble, and that the guides and camp managers of Linyanti Explorations, the concession holders, were praying that the cubs would be all right. I anxiously sought progress reports over coming months, as I found myself quite moved by the calamity which had befallen such a social group of big predators. Like most visitors to Africa, I'd been exposed to life-and-death dramas involving predator and prey, but this was different, no doubt because of the time I'd spent witnessing the lions' family life. The lionesses couldn't walk, let alone hunt, for three weeks; they were forced to lie up near water and in shade until their paws healed. Lions at rest are often cutely supine, their legs splayed and paws drooping in the air. These lionesses were like that for hours, days on end, but they had no choice. Their milk dried up within a week, and the cubs began to get thin and weak. The male lions, visiting the pride from time to time between territory patrols and hunts, didn't seem to understand what was happening. When the females were able to walk again, their paws were too tender for hunting. But it was imperative that they search for food, and when they moved off, their starving cubs stumbled after them in hot pursuit. Eventually, there was hunting success - the lionesses brought down a hippo one night, but it came too late for the cubs. Senior safari guide, Wade Whitehead, believes all 14 cubs had died by the beginning of December. Their mothers were on the verge of starvation too, and feeding themselves took priority over the well being of their cubs to ensure their own survival to bring up a new generation. Whitehead, his colleagues and their clients witnessed the suffering of the pride as the weeks went by, but there was no question of human intervention, even if it had been possible. Nature was left to run its course.

The 'green' time in the first few months of the year is when the animals of the wetlands, woodlands and grasslands of northern Botswana have their young. It's also the time for one of the regular aerial game counts over Selinda's 135,000 hectares, complementing the continuous reporting of wildlife movements and activities by the guides on the ground. It's been with particular relief that this year they've been able to report the Selinda pride's imminent joining in the renewal of life. And Wade Whitehead says the pride is better off, because the baptism of fire has made the lionesses so much more experienced. All images captured with Canon EOS 5, EF 100-400/4.5-5.6L IS, 540EZ flash, beanbag support, Fuji and Agfa slide films. Editor's note - John Milbank is a keen photographer of African wildlife, having made four visits to the continent in recent years. His images can be seen on his personal website. |

|

|

The hunt I witnessed last July was a successful one.

At first, one of the lionesses stayed behind with the 11 cubs. The other

mothers, grandmothers and aunts had quick success, bringing down an

unfortunate zebra for which the cloak of darkness had been no protection.

It was then that I saw the designated nursemaid sprint away from the cubs

towards the sound of the kill, eager to join in the spoils.

The hunt I witnessed last July was a successful one.

At first, one of the lionesses stayed behind with the 11 cubs. The other

mothers, grandmothers and aunts had quick success, bringing down an

unfortunate zebra for which the cloak of darkness had been no protection.

It was then that I saw the designated nursemaid sprint away from the cubs

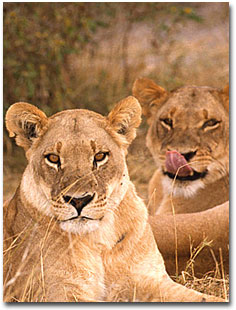

towards the sound of the kill, eager to join in the spoils. Both delighted and awed, I had watched and photographed the lionesses

and their cubs in July, as they hunted, fed, suckled, played and rested.

The sentiments were often simultaneous. For example, when the older cubs

were fetched to the zebra kill, mealtime became a practice session as they

repeatedly pounced on and fell off the carcass, trying to 'kill' it over and

over again.

Both delighted and awed, I had watched and photographed the lionesses

and their cubs in July, as they hunted, fed, suckled, played and rested.

The sentiments were often simultaneous. For example, when the older cubs

were fetched to the zebra kill, mealtime became a practice session as they

repeatedly pounced on and fell off the carcass, trying to 'kill' it over and

over again. For a time, the pride moved away from its stamping ground, making it

difficult to follow its fortunes. It wasn't until the end of the rains and

the new safari season drew near this year that the lionesses were seen to be

healthy and sleek, albeit with some "pink paws," and there were predictions

that they would soon start producing new cubs.

Still preparing for their first clients of the year, the guides spotted

lionesses with five cubs in the open and three other cubs apparently too

small to be brought out of concealment. But it turned out that the new cubs

belonged to other prides, the bigger group from the Savuti Channel pride,

occasional visitors to Selinda. Still, the Selinda pride had been mating

for some time, and there was confidence that its first new cubs would arrive

in late June or early July.

For a time, the pride moved away from its stamping ground, making it

difficult to follow its fortunes. It wasn't until the end of the rains and

the new safari season drew near this year that the lionesses were seen to be

healthy and sleek, albeit with some "pink paws," and there were predictions

that they would soon start producing new cubs.

Still preparing for their first clients of the year, the guides spotted

lionesses with five cubs in the open and three other cubs apparently too

small to be brought out of concealment. But it turned out that the new cubs

belonged to other prides, the bigger group from the Savuti Channel pride,

occasional visitors to Selinda. Still, the Selinda pride had been mating

for some time, and there was confidence that its first new cubs would arrive

in late June or early July.