|

My favorite season for nature photography is winter. The air is

crystal-clear, trees offer stark, graphic forms against a background of

dazzling whiteness and the profound quiet and solitude of a frigid day in

the wild can be an overwhelming natural high.

When everything in nature has turned white, the photographic

challenges are considerable. Keeping your fingers functional in the

intense cold is critical, both for safety reasons and to enable you to work

the controls on the camera and tripod. Cold also affects electronics. The

batteries that power electronic cameras may malfunction when the mercury

drops too low. Another problem is that the front element of each lens must

be protected from wind-driven snow and ice particles. And compositions can

be more difficult to find because many of natures details have been covered

by snow.

The most challenging aspect of shooting in winter, however, is

exposure. The brilliant whiteness that shrouds all of nature fools light

meters into underexposing both slides and negatives. Overcoming this

problem requires careful analysis of each shot and applying some very basic

photographic principles.

How to Handle Exposure

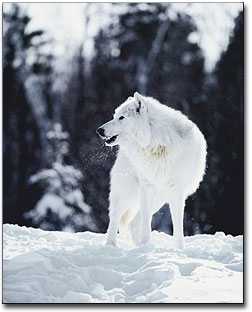

Reflective meters, like those built-in to your 35mm or medium

format cameras, read light bouncing off the subject. Their programmed

response is designed to expose those light values as middle gray (or Zone

V). This works great if the subject is green grass, Navajo sandstone, or a

medium gray wolf. If the majority of a scene is white, however, the meter

still tries to make the exposure medium gray. Consequently, snow becomes

gray -- instead of white -- and the rest of the photograph is similarly

underexposured.

Suppose you take a light reading of the scene and open the lens

aperture (or adjust the shutter speed) by one or two f/stops to compensate.

The underexposed landscape is brightened and the snow is rendered as white.

This sounds great. But do all snowy landscapes reflect the same

amount of light? Is snow under an overcast sky as bright as snow

reflecting full sunlight in a blue sky? Is patchy snow at sunrise more or

less reflective than a complete whiteout where a blizzard is blowing snow

horizontally?

It is obvious that it's impossible to make a general exposure

compensation rule that applies to all situations. So, how do you

accurately expose for a winter landscape? There are two methods to use

that will guarantee perfect exposures every time.

Method No. 1: Use your in-camera or hand held reflective meter to

read a middle toned, or medium-gray, subject: a gray camera bag, a pair of

jeans, a tree trunk or perhaps a rock outcropping. Any middle-toned object

will work (regardless of color) as long as it's receiving the same light as

the scene before you. Once you've determined this reading, manually set

the lens aperture and shutter speed and don't use the automatic exposure

mode to make the shot.

What if there are no medium gray objects nearby? Try this: take a

Kodak gray card to a fabric store and buy a small piece of material that

approximates the tonality of the card. Sew this onto your camera bag and

now you'll always have a medium gray object from which you can take an

accurate reading.

Method No. 2: An incident meter reads the light falling onto a

scene as opposed to light reflecting off of it. The incident meter isn't

fooled by white snow because it determines the amount of light falling onto

the scene from the sky, irrespective of the reflectivity of the subject.

The technique is simple. Point the white hemispheric ball on the

meter toward the camera lens, push a button, and the correct reading is

visible on the crystal display readout. However, the light falling onto

the meter must be the same as the light falling onto the scene that you're

photographing. If you're in the shade and the landscape is lit by the sun,

the reading will be inaccurate.

Keeping Warm

When I was shooting baby harp seals in the Gulf of St. Lawrence,

the temperature dropped to minus 45 degrees F. I remember taking off my

three layers of gloves to change film and, when my skin came directly in

contact with the air and the metal of the camera, they began to hurt so

badly I couldn't focus on photography anymore. I ran back to the warmth of

the helicopter interior until the pain went away and warmth returned to my

hands.

The best solution is to carry either two hand warmers (one for each

pocket) or several chemical heat packets. The hand warmers are powered by

fuel sticks that last about three hours. They provide a tremendous amount

of heat and will keep the pockets in your parka toasty when you need to

revitalize your fingers. The chemical packets can be inserted into your

gloves (or boots) for continuous warmth. Both of these items will prevent

frostbite and will ensure you have manual dexterity for the operation of

your camera.

Protecting Your Camera's Electronics and Optics

Most 35mm and medium format cameras today are either fully

electronic or have electronic components. In extremely cold weather

conditions, batteries will stop functioning.

When I'm not shooting, I open two or three snaps on my down parka

and place the camera against my body. I shoot primarily the Mamiya RZ 67,

which is a sizable camera. Nevertheless, I hold it against me and the heat

generated by my body keeps the battery warm enough to work. If I know that

I'll be carrying the camera on a tripod for long stretches, where it would

be awkward to constantly take it on and off, I'll duct-tape a couple of the

chemical heat packets to the bottom of the camera where the battery is

located.

To protect the front lens elements from blowing snow and ice, I

habitually use lens shades. In addition, a skylight filter acts as a first

line of defense in protecting the vulnerable lens should snow or sleet

freeze on the glass.

Winter Compositions

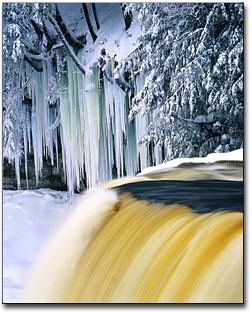

Winter compositions require a discerning eye to find. Look for

strong, graphic shapes and startling contrast. Bare branches against snow

or a weathered split-rail fence protruding from snow drifts are classic

images. A majestic snow-covered mountain range composed with a deep blue

sky always offers a dramatic shot. The same range of mountains

photographed against a white sky can also be exquisite. My favorite

subject in nature is shooting white on white.

Don't forget to use low angled sunrise or sunset lighting to

enhance the rich texture of a fresh snowfall or to backlight ice on frozen

reeds in a pond. Winter landscapes are dramatized by golden light in the

early morning and late afternoon. Snowflakes often catch the light, adding

sparkle to your picture. Long shadows offer a graphic element as they

stretch out on the pristine white snow.

Enjoy winter photography this year. Use these simple guidelines,

and the challenges of shooting in white conditions and frigid temperatures

will pay off many times over.

Jim Zuckerman left his medical studies in 1970 to turn his

love of photography into a career. He has lectured and taught

creative photography at many universities and private schools,

including UCLA, Kent State University, the Hallmark Institute of

Photography, and the Palm Beach Photographic Center. He also has led

international photo tours to destinations such as Burma, Thailand,

China, Brazil, Eastern Europe, Alaska, Greece, Papua New Guinea, and

the American Southwest.

Jim Zuckerman left his medical studies in 1970 to turn his

love of photography into a career. He has lectured and taught

creative photography at many universities and private schools,

including UCLA, Kent State University, the Hallmark Institute of

Photography, and the Palm Beach Photographic Center. He also has led

international photo tours to destinations such as Burma, Thailand,

China, Brazil, Eastern Europe, Alaska, Greece, Papua New Guinea, and

the American Southwest.

Zuckerman specializes in wildlife and nature photography,

travel photography, photo- and electron microscopy, and digital

special effects.

Zuckerman is a contributing editor to Petersen's Photographic

Magazine. His images, articles and photo features have been

published in scores of books and magazines including several

Time-Life Books, publications of the National Geographic Society,

Outdoor Photographer, Outdoor and Travel Photography, Omni Magazine,

Conde Nast Traveler, Science Fiction Age, Australia's Photo World,

and Greece's Opticon. He is the author of seven photography books:

Visual Impact; The Professional Photographer's Guide to Shooting and

Selling Nature and Wildlife Photos; Outstanding Special Effects

Photography on a Limited Budget, Techniques of Natural Light

Photography, Jim Zuckerman's Secrets of Color in Photography, Fantasy

Nudes, and Capturing Drama in Nature Photography.

His work has been used for packaging, advertising, and

editorial layouts in thirty countries around the world. Jim's images

have also appeared in calendars, posters, greeting cards, and

corporate publications. His stock photography is represented by

Corbis Images.

To learn more about Jim and to view his work, visit his web site at www.jimzuckerman.com.

|