|

|

Species Profile...

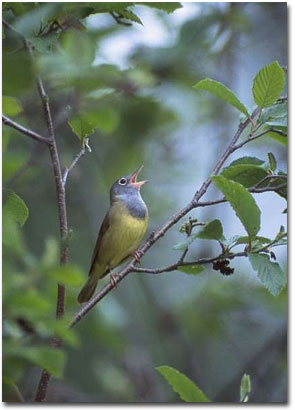

Photography Copyright Kathy Adams Clark All rights reserved. Quest for the Connecticut Warbler

A Connecticut warbler is not a rare bird, but it's by no means common. It's also not a bird typical of Connecticut. The nineteenth century ornithologist, Alexander Wilson, named the bird for Connecticut because that's where he first saw the bird, probably during migration. I don't often have the chance to visit the places where the Connecticut warbler hangs out. The bird breeds in the early summer in the boreal forests of central Canada, northern Minnesota, and northern Michigan. Its favorite breeding grounds are boggy spruce forests where uncountable masses of mosquitoes, black flies, and ticks feed mercilessly on human flesh. The bird spends the winter in the deep, virtually inaccessible Amazon Basin of South America. No one visits that area very often. According to the book, A Field Guide to Warblers of North America by Jon Dunn and Kimball Garrett (Houghton Mifflin, 1997), Connecticut warblers migrate in the spring from South America to the Caribbean, across to Florida, through the Ohio Valley and onto a narrow range of boreal forests on the North American continent. In the fall, the birds typically migrate eastward to the New England states and south along the Atlantic Coast to North Carolina's Outer Banks. From there, most birds appear to fly straight over the Atlantic Ocean to South America. Of all the North American breeding warblers, the Connecticut warbler is by far the most difficult to find. It's reclusive and doesn't normally respond to the owl whistling, squeaking, and swishing noises birders make with their mouths in order to draw birds into view. Most people who see the bird get only a brief view. The Connecticut warbler (Oporornis agilis) is a handsome bird, well worth the trouble of searching for it. It's in the same genus as the mourning warbler, MacGillivray's warbler, and Kentucky warbler. It has olive green upper parts, lemon yellow under parts, and striking gray coloring on its face, head and throat. The bird has a big, dark eye circled by a conspicuous white eye ring. It has big feet and, unlike most warblers, it walks rather than hops along tree branches. The song of the Connecticut warbler is a spirited, chirping sound that a friend in Minnesota described as sounding like the syllables, tu-chibee-too, chibee-too, chibee-too. Its call note is a sharply pitched chimp sound. The song is ventriloquial-you may think you're looking in a tree where the warbler is singing, but it's probably singing from a different tree. Just another one of the bird's tricks to keep you from seeing it. I was determined to find a Connecticut warbler this year while in Minnesota after one of my wife's photo workshops. I contacted Gretchen Mehmel, Manager of the Red Lake Wildlife Management Area in Northwestern Minnesota. She directed me to an expansive spruce forest at Red Lake where the warblers were breeding. Early on the morning of June 8, my wife and I headed down Rapid River Forest Road, which skirted the edge of the spruce forest that Mehmel told me about. The forest was densely packed with tall, black spruce trees and tamarack pines. The road itself was lined with 10-foot high willow and alder trees. A wide ditch with knee high, murky water separated the forest from the road. We got out of our rented four-wheel drive truck and listened. We could hear the Connecticut warbler singing deeply inside the forest. We could also hear the songs of numerous other warblers and vireos, plus the drumming sound of a grouse. Peering into the forest with our binoculars, we could only see the bluish-green cast of the trees and the mossy green cover of the forest floor. Mosquitoes and black flies engulfed us. At one point, blood was streaming down my wife's neck from the bites of ferocious black flies. After years of refusing to spray herself with insect repellant, she learned to love the stuff. We drove along the road, getting out periodically, listening, looking, and hoping to see the warbler without having to hike into the spruce jungle. After two hours of hearing but not seeing the warbler, we prepared to plunge into the forest. All of a sudden, the telltale chimp call note of the warbler came from a willow next to the road. We looked out the truck window and not ten feet away was a male Connecticut warbler. It reared its head back and rang out its vigorous song, tu-chibee-too, chibee-too, chibee-too. It moved into an adjacent alder tree, gleaning insects, singing, displaying, preening, and walking along the branches. The bird flitted back and forth from the willow to the alder for about 45 minutes. Kathy shot three rolls of film, maybe more, I'm not sure. All I hope for is a portrait of that bird to put above my desk at work. About the image... Nikon F100 camera Gary Clark and Kathy Adams Clark - NPN 134 Gary Clark is a writer and associate dean of natural sciences at North Harris College in Houston, Texas. Kathy Adams Clark is a professional nature photographer. Learn more about them at www.kathyadamsclark.com. Comments on NPN wildlife photography articles? Send them to the editor. |

|

|

For years, my most sought after bird was a Connecticut warbler. It was the only regularly occurring North American warbler that I had not seen. I finally saw it this June in northern Minnesota.

For years, my most sought after bird was a Connecticut warbler. It was the only regularly occurring North American warbler that I had not seen. I finally saw it this June in northern Minnesota.