Most accomplished nature photographers will tell you that preplanning is essential in order to increase the number of "keepers" from a photo shoot. Knowing in advance what to expect in terms of light, subject location (and subject behavior for fauna subjects), weather and equipment requirements are just a few of the considerations that go into planning a successful outing.

But those same photographers will also tell you to be prepared for the unexpected. This is what I call Nature's chaos in the figurative sense. Despite all of our planning, Mother Nature often reminds us that the weather, the quality of light, and availability of subjects are under her control, not ours.

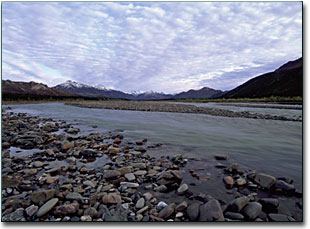

It was late August in Denali National Park. It was my last full day in the park after having spent a week there. Denali has been called America's Serengeti, full of impressive wildlife living as it did before humans arrived, amidst the backdrop of breathtaking scenery on a grand, Alaskan scale. It is what biologists call a complete and intact ecosystem. A couple of days earlier, I had set up camp at Teklanika River campground. According to the park rangers, wolves are known to travel the riverbed in search of prey. Dall sheep can easily be found at the higher elevations of nearby Igloo and Sable Mountains. And to top things off, within the last two days, a sow Grizzly and her cub have been sighted feverishly digging roots along the river to put on the last few pounds of fat before retiring to their den for the winter. So my expectations for the final day of shooting were high. Get up early to catch the morning light, look for wildlife along the riverbed, and hike several hundred feet up to capture Dall sheep on film.

Overnight, the clear skies brought the coldest morning yet to Denali. My tent and the surrounding wilderness were covered in a hard frost. There was not a cloud in the sky to capture alpine glow. I wandered along the riverbed, scanning my immediate horizon for any sign of wolves or grizzlies. Nothing. The day was not turning out as I had planned.

As I walked along one of the myriad of side streams of the Teklanika River, towards Igloo Mountain and visions of Dall sheep, my eye caught an intricate design sparkling in the rising sun. A delicate sheet of ice crystals lined the edge of the river and I found myself spellbound in child-like fascination. These jewels of nature served as a fleeting reminder of the temporary cold of the night, and just maybe, the more enduring cold to come. Hanging precariously above the rushing water, the ordered crystals would soon fall victim to the radiance of the sun, lose their shape and ultimately their identity, to join the randomness of the river once again. This reality soon brought me back to the task at hand - capturing this beauty on film.

No sooner had I finished with the ice crystals than the river showed me how its turbulence can create order to rival the frozen molecules of water. Along the river bottom was etched a graceful sculpture of silt, fashioned by the random hand of the crystal clear and cold, yet flowing liquid molecules of water. There was an otherworldly quality to the pattern, as if I was seeing the surface of Mars through the lens of a NASA space probe. Finally, my brain engaged. The ice crystals and the silt are the chaos of Nature in the literal sense; this is chaos theory in action. James Gleck so eloquently described this highly mathematical concept to the layman in his best selling 1987 book, Chaos. Three years later, he and master landscape photographer Eliot Porter would show how nature preeminently creates "irregular order from pure disorder" in Nature's Chaos:

"The study of chaos has provided a seemingly paradoxical insight: that rich kinds of order, as well as chaos, can arise - arise spontaneously - from the unplanned interaction of many simple things. Cooperation arises in nature, or the illusion of cooperation, not just in animate beings but in the inanimate as well. The results are hypnotic."

I began to wonder. Could those same water molecules that shaped the sandy particles of eroded rock along the river bottom once been constrained and immobilized by geometry in some earlier life as an ice crystal?

Before I realized it, the early morning has turned into mid afternoon. The time to depart in search of Dall sheep at the higher elevations in reasonable light had come and gone. As I began to pack up my gear, the once cloudless sky beckons me to take one more picture of Nature's chaos. High above me, stretching to the horizon, were the rippled patterns of clouds. Small droplets of water, maybe even some minute ice crystals, formed by random and not so random streams of wind. The next day it rained; the molecules of the sky joined the molecules of the earth and Nature's chaos began anew.

As I headed toward my campsite to call it a day, I ran into two acquaintances I met on the camper bus coming from Wonder Lake a few days earlier. They were overflowing with excitement about the day they had on top of Igloo Mountain, where they had sat among numerous Dall sheep, at ease in their high elevation homes away from four legged predators, and willing to pose for the dozens of photos they took. Just for a moment, I thought of the opportunity I had missed. In retrospect, would I trade it for the day I had? No. Because I know that I had captured the essence of the day on film. For me, that is what nature photography is all about.

So the next time Mother Nature changes your plans, be prepared for the unexpected. You never know what part of the intricate web she will reveal next.

About the images...

Ice Crystals

Denali National Park, Alaska, Teklanika River

Nikon F5

Tamron 90 mm f/2.8 macro

Bogen 3001 tripod with 3030 head

Fuji Provia 100F rated at ISO 100

f/22, shutter speed not recorded

No filtration, no flash

Photo taken by Ray Bulson, 2000

Silt

Denali National Park, Alaska, Teklanika River

Nikon F5

Tamron 90 mm f/2.8 macro

Bogen 3001 tripod with 3030 head

Fuji Velvia rated at ISO 40

f/22, shutter speed not recorded

No filtration, no flash

Photo taken by Ray Bulson, 2000

Alaskan Landscape

Denali National Park, Alaska, Teklanika River

Pentax 645N

Pentax 35 mm f/3.5

Bogen 3001 tripod with 3030 head

Fuji Velvia rated at ISO 40

f/22, ½ second

2-stop Hard Edge Singh-Ray ND filter

Photo taken by Ray Bulson, 2000

Editor's note: Ray Bulson is a NPN reader who resides in Newark, Delaware. More of his work can be seen on his web site, Wilderness-Visions.com.